The Acropolis

SIGNIFICANCE

Status as Unknown in the Renaissance

In the Renaissance, the Acropolis was virtually unknown and had no direct influence on Renaissance architects, who looked to ancient Roman architecture for models.

Indirect Influence

The Acropolis and its buildings were indirectly influential, however, because they were known to architecturally significant ancient Romans such as Vitruvius and Hadrian, whose respective writings and patronage of important buildings affected Renaissance architects decisively. Because Roman architecture evolved from Greek architecture, an introduction to Roman architecture must include some background to the latter. And, any discussion of Greek architecture would be incomplete without the Parthenon and the other buildings of the Acropolis, the supreme exemplars of Classical Greek architecture.

Publication of the Acropolis

Knowledge of the Acropolis was first disseminated by Stuart and Revett's 1787 publication, Antiquities of Athens, which contributed to the popularity of Greek-style architecture, furniture, and clothing in Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

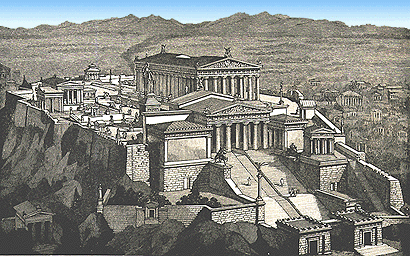

THE SITE

The Name "Acropolis"

As suggested by the name "Acropolis," a fusion of the words for "summit" (acro) and "city-state" (polis), the site is located at the top of a hill overlooking the city.

Elevated Site

In elevation, the Acropolis is around 500 feet above sea level and 300 feet above the city.

Using elevated sites for fortified palaces was a common practice in ancient Greece for both the Mycenaeans and the Hellenic Greeks, who supplanted them. Hilltops were also used as religious precincts for temples, and in times of invasion, they served as places of refuge for the population.

Geology

The plateau was formed of limestone, whose whitish coloring added to the majesty of the gleaming marble buildings.

PRE-450 BC CONSTRUCTION

Fortress Built in Mycenaean Era

In the second millennium BC, when the Mycenaean civilization occupied mainland Greece, the Acropolis of Athens was used as the site of a fortress containing a palace. The Mycenaean civilization collapsed in the twelfth century BC and was succeeded by the Hellenic Greek civilization.

Little on the Acropolis plateau remains from the Mycenaean period except for the 15-feet thick wall belting the hill. Its masonry is Cyclopean, built using huge, irregular blocks that were laid without cement. This masonry came to be called "Cyclopean" because the successors of the Mycenaeans were overwhelmed by the size of the blocks and believed such walls could only have been built by giants like the Cyclopes, a race of one-eyed giants known in Greek mythology.

War with Persia and Affects on Acropolis

The Persian Empire, which had become the dominant power in the Near East under Darius and Xerxes, attacked Greece in 490 BC and was defeated by the Athenians at Marathon. To celebrate this victory, the Athenians began a new and larger temple dedicated to Athena to replace the stone temple that had been built in the early sixth century BC, near the end of the Archaic Period (700-480 BC) of Greek architecture. Within a decade, the lowest drums were in place.

In 480 BC, the Persians returned with a larger force. After the Persians broke through the Greek defenses at Thermopile, Athens was abandoned, and the Persians razed the Acropolis, destroying all its buildings.

Later that year, the Greeks defeated the Persians decisively in a naval victory at Salamis, and in 479 BC, they expelled them from the mainland.

PERICLES' LEADERSHIP IN REBUILDING

Initiating Rebuilding

Although they had overcome their Persian enemy thirty years earlier, the Greeks did not embark on a vigorous program of rebuilding the Acropolis until Pericles became the leader of Athens in 450 BC. The temple dedicated to Athena was the first structure to be rebuilt. This misappropriation of funds was one of the factors leading to the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC.

Use of Pentelic Marble

Pentelic marble, a high-quality, white marble that is quarried nearby at Mount Pentelikon, was used for the construction and sculpture of the buildings on the Acropolis. In the fifth and fourth centuries BC, Pentelic marble was used for only the city's most important buildings.

Construction Speed and Funding

To finance the rapid pace of the construction of the Acropolis, which would have required an army of workers and more funding than the Athenians could have afforded, Pericles used funds from the Delian League treasury, which had been moved to Athens in 454 BC from its original location on the island of Delos. This fund had been established for mutual defense by over two hundred Greek city-states. This misappropriation of funds was one of the factors leading to the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC.

Orientation of Buildings

Except for the Parthenon, which is south of the location of the original temple of Athena, the locations and orientations of the Archaic-period buildings of the Acropolis are reflected by the positions of the buildings that replaced them in the fifth century. Instead of being aligned with each other, the buildings are oriented individually according to the sacred spaces of the deities (gods) to whom each is devoted.

When the Acropolis was restored, all post-Greek construction was removed.

PARTHENON, 447-32 BC

Construction

The first of the buildings on the Acropolis to be re-built was the Parthenon, a Doric-order temple, which was designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates. The building was begun in 447 BC and finished in 438 BC. Completion of the sculpture took another six years. Pentelic marble was used everywhere including the roof, which was usually made of terracotta tiles.

Alignment with Compass Points

The Parthenon is roughly aligned with the compass points so that the ends face east and west and the sides face north and south.

Viewing the Parthenon

In the fifth century BC, the west end of the Parthenon was blocked from view from the procession route on the Acropolis plateau because of the Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia and the armory.

The temple's other end could be seen from the eastern side of the Acropolis, which could be reached by walking past the Parthenon's north facing after entering from the western gate or by entering the Acropolis through a secondary entrance on the northeast side.

Basic Design

The Parthenon followed the traditional Greek-temple form in having a cella surrounded by a peristyle. It was larger than most Greek temples in being eight-columns wide instead of the more common six.

The cella was divided into two unconnected chambers, which were entered from the ends of the building through second rows of Doric columns that were slightly smaller than those of the peristyle.

The larger chamber to the east contained a colossal statue of Athena. Its ceiling and roof were supported by a pair of superimposed Doric-order colonnades that divided the space into a center and side aisles.

The smaller chamber to the west housed a treasury of temple property and funds belonging to the Delian League. Its ceiling and roof were supported by four Ionic-order columns, which were proportionately taller and more slender than the Doric-order columns.

Proportions

The column diameter at the base is a module that defines a number of other proportions such as the intercolumnation (spacing of column centers).

The peristyle was eight-columns wide on the ends and seventeen-columns wide on the sides, and after adding in the spaces between them, the length-to-width ratio is 9:4.

Refinements

The Parthenon has long been considered the epitome of Greek-temple design because of its harmonious proportions and refinements. The refinements, which were used on other Greek temples as well, seem to have been intended to counteract optical illusions that would make the building appear imperfect.

●Entasis. A slight bulge in the column shape, called entasis, counteracts the tendency of the column sides to appear dished inward.

●Curving horizontal lines. A slight convex curve of both the base and the entablature counteracts the tendency of the middles of these wide horizontal expanses to appear sagged. Curving the floor slightly upward in the center also had the practical advantage of draining rainwater effectively.

●Inward lean. A slight inward lean of the columns and walls counteracts the tendency of these parts to appear to be falling outwards. The inward lean is so slight that if lines from them were extended upward, they would not meet for 1.5 miles.

●Variable thickness. Thicker columns are used at the corners because columns seen against the cella walls, which are shaded by the porch, appear more massive than columns that are seen against the lightness of the sky.

Later Uses as Church and Mosque

In the sixth century AD, the Parthenon was consecrated as a Christian Church. An entrance passage through the former treasury chamber was opened, and the entrance to the sanctuary of Athena was made into an apse, which required the removal of several columns.

After the Turks conquered the Byzantine Greeks in 1458, they added a minaret to the Parthenon and used it as a mosque. The Turks later converted it to a garrison, which brought about its partial destruction.

Damaged Condition

In 1687, after having remained intact for 2125 years, the Parthenon was damaged during in a war between the Venetians and the Turks, who still occupied Greece. The Turks stored gunpowder inside the building, whose visibility made it vulnerable to attack. A cannon ball exploded the gunpowder, blowing out the roof and toppling many of the columns at the centers of the long sides. Those on the north facing were restored before those on the south facing.

The building's original appearance can be imagined from a model.

SCULPTURE PROGRAM AT THE PARTHENON

Overview

The Parthenon was enriched by an ambitious program of sculpture of the highest quality. It was overseen by the Greek sculptor Phidias, who had a large workshop of many workers. Phidias was innovative in his ability to form harmonious groupings of figures in motion and to use drapery to express action and mood.

Free-Standing Sculpture in the Pediments

The pediments contained arrangements of over-life-size free-standing figures representing the gods in poses that accommodated its triangular shape. Athena, the city's patron, was the subject of both pediments. At the west end she fights the sea god Poseidon for patronage of Attica, and at the east end, she is born, armor and all, from the head of Zeus.

Relief Carving on the Metopes

The metopes were carved in high relief and depict fights between pairs of combatants. These contests alluded to the Athenian defeat of the Persians, who are symbolized by the less civilized figures such as Trojans (north facing), giants (east facing), centaurs (south facing), and Amazons (west facing).

Relief Carving on the Frieze

On the long sides of the Parthenon, the frieze is located on the top of the cella and on the entablatures of the inner rows of columns on the short ends.

The subject of the frieze is generally taken to be the Panathenaic Procession, in which Athenians participate in a procession to bring the Peplos, a dress woven of golden thread by virgins, to the Acropolis as a birthday present for Athena. Priests then re-clothe an ancient wooden statue of Athena, which was housed in the Erechtheion beginning in 405 BC. The procession is depicted as two lines extending from the rear (west end) of the temple along the sides and coming together at the front (east end), where the gods, who are larger than the humans, are seated. Because the gods and humans do not interact, it is assumed they are in different realms.

It has been argued that 192 of the figures in procession, most of the young men excluding the charioteers, are meant to represent the 192 Athenian heroes who died at the Battle of Marathon. (Had the Greeks been defeated then, it is unlikely that the splendid flowering of Greek culture in the fifth and fourth centuries would have occurred.) Historians who accept the interpretation of these figures as the Marathon heroes are divided as to whether or not they are meant to be within the context of the Panathenaic procession. Much of the frieze illustrates a cavalcade of young men on horses. The procession also includes a number of maidens, youths, elders, and sacrificial animals.

Chryselephantine Colossus inside Cella

Inside the cella stood a colossal statue of Athena (c. 460 BC) by Phidias. In a manner known as "chryselephantine," the figure's draperies were made of beaten gold, and its flesh parts were encrusted with ivory. These materials were attached to a hollow wooden core.

Removal of Sculpture from Site

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the wealthy Englishman Lord Elgin, who was the British ambassador to Constantinople, received permission from the Sultan to remove sculpture from the Acropolis. He wished to save it from further damage and deterioration at the site, where much of it had been left unprotected since the explosion.

Lord Elgin later sold the sculpture to the British Museum in London for 35,000 pounds. What he took from the Parthenon represents about half the sculpture from the site that survives today.

He also took one of the six caryatids from the Erechtheion.

Basic Layout

The Propylaia, which was located at the West end of the Acropolis, was its principal entrance. Its elevated location required visitors to approach it from below using the stairs or the ramp directly in front. Another set of stairs within the structure elevated the building's rear portico, which opened onto the Acropolis.

The Propylaia was designed by Mnesikles. Its space was organized into a wide center and two wings, which had been designed to be considerably larger than the structure actually built.

Central Section

The central section of the Propylaia resembled a temple in having colonnaded ends carrying pediments. To accommodate a procession that included wheeled vehicles, horses, and animals for sacrifice, the central ramp continued through the center, which was wider by one triglyph and one metope.

The ceiling of the central hall was supported by two lines of three Ionic columns. These colonnades divide the space into three aisles, which corresponded to the ramp flanked by steps at the entrance.

Wings

The wings were positioned to extend forward, thereby creating an embracing U-shape. Doric porticos in a smaller scale than the central portico stood at right angles to it.

The left wing contained a gallery for pictures painted on wooden panels, and this is believed to be the first picture gallery in history.

On the right side, only the portico of the wing was built.

Use of Both Doric and Ionic Orders

The use of both the Doric and Ionic orders is believed to be symbolic of the site's serving worshipers from all of Greece, not just Athens.

Unfinished State

Construction was halted in 431 BC, the first year of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and an alliance formed by Sparta. Larger wings with porticos facing the Acropolis had been planned, and much finishing detail was omitted.

Damaged Condition

Although ignited by lightning rather than cannon fire, the Propylaia shared the fate of the Parthenon in having its roof blown off in the seventeenth century by an explosion of gunpowder stored within by the Turks.

TEMPLE OF ATHENA NIKE, 427-24 BC

Site

The Temple of Athena Nike rises from a bastion that is strategically located beside the vulnerable sloping terrain at the entrance to the Acropolis.

Here, as at other key military sites, deities associated with war and victory were honored.

The Name "Athena Nike"

The temple is named for and dedicated to Athena Nike, a fusion of Athena, the patron goddess of Athens, and Nike, the Greek deity personifying victory. Nike statues were commonly made as winged females like the famous Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre.

Establishment of Sanctuary

In 449 BC, the Athenian government decreed that a sanctuary for Athena Nike would be established on the earlier temple's site, the sacred precinct of Athena Nike.

The temple building was constructed between 427 and 424 BC, but the parapet frieze was not installed until around 410 BC.

Design

The architect believed to have been the principal designer of the Temple of Athena Nike is Kallikrates, who is known to have designed a similar temple.

The Temple of Athena Nike is unusual for being small and having columns only on the ends instead of having a peristyle with columns on all sides.

The pitched roof with pediments at the ends is now missing, but the four-column porches at the front and back remain. The temple is the first building on the Acropolis to use the Ionic order.

Pentelic marble is used throughout, even for the roof.

Destruction and Restorations

Like the other buildings on the Acropolis, the Temple of Athena Nike remained in good condition until the 17th century when this site was again used as a fortress. It was held by the Turks, who occupied Greece at that time and were besieged by the Venetians. Unlike the Parthenon and the Propylaia, whose roofs were blown off when the gunpowder stored there by the Turks was ignited by cannon fire and lightning, the Temple of Athena Nike was dismantled by the Turks, who re-used its blocks to build a bastion on another facing.

After the liberation of Greece and the restoration of the monarchy in 1834, the bastion that was constructed using blocks from the Temple of Athena Nike was dismantled, and most of the temple's blocks were found and used in its reconstruction.

The building has been dismantled and restored using metal and concrete twice in the 20th century: in the late 1930s and the late 1990s.

Site

The upward slope of the site of the Erechtheion from the northwest toward the southeast contributed to the building's irregularity and is reflected by the differing floor levels of the various parts.

Critical factors in determining the placement of the Erechtheion and its various parts were the positions of the sacred sites of the deities served by it.

The legendary contest between Poseidon and Athena took place here, and the trident mark where Poseidon struck a rock and produced water is located under an opening in the floor of the north porch.

Design

The Erechtheion was designed by the Greek architect Kallikrates and others.

Although the body of the Erechtheion was rectangular, the building is given a highly unconventional asymmetry by the irregular placement of two of its three porches.

The enclosed area of the Erechtheion consists of two distinct parts that have different floor levels and no door connecting them. The two spaces are unified into a single block by the roof. The use of the slender and graceful Ionic order in harmoniously proportioned groupings also added to the building's unity.

Use of the Ionic Order

The Erechtheion is executed using the Ionic order. It is much admired for the refinement of its details such as the frames of doorways and the ornamentation on the orders.

Deities Served

Although it is now known by the name of the god Erechtheus, the Erechtheion was built to serve several deities of whom the two most important were Athena Polias and Erechtheus.

●Athena Polias. The name Athena Polias refers to Athena's role as patron of the city, a status won in a contest with Poseidon by her contribution of the olive tree, whose oil was a valued commodity. A part of the sanctuary is believed to have sheltered the first olive tree. The part of the temple forming her sanctuary, which is now thought to be the eastern cella, contained the sacred wooden statue of Athena that was given a freshly made robe every four years as part of the Panathenaic Festival.

●Erechtheus. Erechtheus was a legendary hero-king of Athens. In such images as the Parthenon's colossus, he is symbolized by a snake. A den of snakes was located beneath the North porch.

Porch of the Maidens

The most striking feature of the Erechtheion is the Porch of the Maidens, which is named for its caryatid supports. The figures are posed symmetrically so that the bent leg of each figure is toward the inside.

Imitations

The Porch of the Maidens has been much admired and widely copied from ancient times to modern.

In the second century the Roman Emperor Hadrian had copies made of these caryatids for his imperial villa at Tivoli near Rome. (It was a common practice for cultured, affluent Romans to commission reproductions of Greek masterpieces, and much of our knowledge of Greek sculpture is based on Roman copies.)

Whole porches have been reproduced in times of classical revival. In the nineteenth century, when architectural styles were eclectic and a number of past styles were revived and adapted to the times, a caryatid porch was incorporated on the side of St. Pancras New Church (1819-22) in London, which was designed by William Inwood and his son Henry William Inwood.

Because of their fame and familiarity, the Erechtheion caryatids have been exploited as attention-getting devices for commercial structures like storefronts.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back