The Profession of Architect

Province of the Architect

In the Renaissance, the scope of the architect was far broader than it is today. It included such enduring forms as palaces, churches, piazzas, and fortifications as well as temporary structures like stage sets and decorations for ceremonies and special events. Mechanical devices such as hoists and weapons for war were also the province of the architect.

Design Versus Construction

The two principal steps required to create a building are design and construction. Today these stages are associated with the separate professions of architect and contractor, but both phases were generally the responsibility of the same person during the Middle Ages and much of the Renaissance, when the transition toward separating them and forming the modern conception of an architect began.

The first Renaissance architect to be divorced from the on-site supervision of a building was Alberti, who had been educated as a scholar and as a gentleman. His role was similar to that of modern architects, who prepare detailed drawings and consult with clients and contractors, who may be elsewhere.

Financial Success and Palace Ownership

By the sixteenth century, many of the leading architects were financially successful and able to afford fine palaces for themselves. In 1517 the artist and architect Raphael purchased the Palazzo Caprini, a much-copied palace designed by his architectural mentor, Bramante.

In northern Italy, architects who built palaces for themselves include Giulio Romano (Mantua), and Leone Leoni (Milan), whose palace was known as "Casa degli Omenoni" ("House of the Big Men" in Milanese dialect) in reference to the herms decorating the façade.

Pre-Renaissance Architects

●Ancient Architects. In ancient Greece, the term architekton, which can be translated as ‘craftsman’ or ‘master carpenter,’ referred to an individual who was associated with designing buildings and coordinating the work of the various craftsmen involved in their construction. Mechanics was also within the province of the architect in ancient times. Architectural theories and practices were discussed in Greek and Roman treatises, but Vitruvius' De architectura is the only one of these to have survived.

●Medieval Architects. In the Middle Ages, the head mason performed the duties of the architect. In accordance with the system of guilds and independent workshops under experienced masters, separate contracts were drawn up between the patron and the workshops of the various crafts involved with construction. This remained the case in the Renaissance.

Education and Status

In the Renaissance, the architect's training emphasizing technique and experience was broadened to include a humanist education, which incorporated Classical forms and principles as well as mathematics.

Because the mechanical arts were less respected than the Liberal Arts, the architect's status was elevated by this change in educational focus.

Most architects in Renaissance Italy had backgrounds in construction, painting, or sculpture, and the label of "architect" was rarely used.

Backgrounds in Construction

Many architects came to their positions after having completed a number of smaller commissions in their trades of carpentry or masonry. They had generally worked as apprentices and assistants for masters in these fields, although some architects were born into families that made carpentry or masonry a family business.

=Sangallo Family. The sons and grandson of Giovanni da Sangallo, a woodworker in Florence, became the successful architects Giuliano da Sangallo, Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger.

=Palladio. Andrea Palladio initially worked as a stone-carver. His early patron, Giangiorgio Trissino, recognized his talent and gave him a humanist education. He also took him to Rome, where important architectural works, both ancient and contemporary, could be seen.

Backgrounds in Painting or Sculpture

Many architects came to that profession after periods of training and work as painters or sculptors.

=Brunelleschi. Brunelleschi, who had been trained as a sculptor and a goldsmith in the early fifteenth century, turned his attention to architecture after failing to win a competition of the commission for a pair of bronze doors for Florence Cathedral's Baptistery of San Giovanni. A trip to Rome opened his eyes to the order and coherence of ancient architecture, and after returning to Florence, he focused on architecture.

=Bramante. Bramante was a successful painter in Urbino before moving to Milan, where he is first known to have worked as an architect. There at Santa Maria presso San Satiro, he combined painting and architecture by using a trompe l'oeil painting to create the illusion of a three-bay chancel at the church's nearly flat altar end, which could not be expanded.

=Michelangelo. Michelangelo, who never abandoned the painting and sculpting activities that made him famous in the first two decades of the sixteenth century, worked as an architect for the Medici family in Florence in his middle years (1516-34) and for the Papacy in his late years (1546-64).

DISSEMINATION OF INDIVIDUAL STYLES

Introduction

There were several ways in which the styles of individual architects influenced others.

Architectural

An architect's buildings are the most direct evidence of his style. Consequently, the cities where the major architects and their followers worked had a significant impact on the dissemination of their styles.

Personal Contact

Architects passed on their ideas to their apprentices and assistants as well as to masons, craftsmen, and others involved in construction.

●Brunelleschi's influence. In the fifteenth century, Brunelleschi's style dominated the architecture of Florence and was taken to other cities by local followers who moved or worked for patrons elsewhere.

●Alberti's influence. Alberti's service as a papal secretary led to his living in a number of cities. Alberti's ideas were known to those of his circle through handwritten manuscripts of his treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, which were passed around before the treatise's publication in 1485. He also had contact with local architects who supervised the on-site construction of his designs.

●Bramante's influence. While living in Rome at the end of his career, Bramante had a wide following in the architectural community. Although his work was concentrated in Milan and Rome, the relocation of his followers in the 1520s spread elements of his style to distant cities.

Treatises

Treatises on architecture, which were passed around in manuscript form and printed, enabled architects to communicate a broader range of ideas than could be reflected by their own buildings and allowed them to reach a wider audience than their local community.

Editions of Vitruvius' treatise and printings of treatises written in the Renaissance were increasingly available.

Drawings

Architects made drawings to work out ideas, communicate their designs to patrons and craftsmen, and record buildings.

Drawings of buildings by architects, which were often preserved by their assistants or family, were another avenue through which architects passed on their ideas. Peruzzi's influence was amplified by the use of his drawings in a treatise by his assistant Serlio, to whom he bequeathed his portfolio.

REPRESENTATIONS OF ARCHITECTURE

Need for Standardization

The practice of separating the design process from the actual construction on the site made it essential to standardize a system of communication between architects and construction supervisors. Existing forms of architectural representation such as plans and models continued to be used, and new forms were invented.

Models

A model is a scale replica, usually of wood, of the architect's design. It was often executed by a carpenter. Models helped patrons visualize an architect's designs and guided masons and craftsmen in carrying them out. Models were used not only for whole buildings but also for parts such as domes, façades, and trim details, which were sometimes made full size.

An uncommon form of model, a full-size mock-up, was once used by Michelangelo at the Palazzo Farnese. Before proceeding with the construction of an especially large cornice, a ten-foot high mock-up of a section was hoisted into place so that he and the patron could evaluate its size and design in relation to the whole building.

Because of their expense, models of whole buildings were only used for important projects like churches and large palaces.

The introduction of more precise forms of graphic representation made models less essential.

Perspective Drawings

The introduction of linear perspective in the fifteenth century enabled artists and architects to produce more realistic images of buildings, which was helpful in visualizing unusual designs.

In his treatise on architecture, however, Alberti advised against relying on perspective drawings during the design process because their illusionistic effects might blind the architect to the actual proportions.

Orthographic Projections

An orthographic projection, also called an "orthogonal projection", is a two-dimensional representation that corresponds in form and proportion to an object as if imaginary parallel lines were projected at right angles to the picture plane. Elevations, sections, and plans are all orthogonal projections. Plans represent horizontal planes, and elevations represent vertical planes.

Orthogonal projections enabled architects to communicate their intentions to builders and craftsmen with great precision. Alberti called for their use in his treatise.

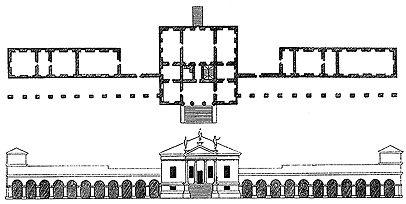

=Plans. A plan is a representation of a building as if it were sliced horizontally and the upper portion removed to reveal the arrangement of walls, windows, supports, and stairways. Ceiling vaults and floor patterns may also be included. Plans may be difficult to comprehend without some knowledge of how supporting members, floors, and ceilings are represented. Inferences regarding a building's height or period can also be drawn from plans. Plans have a long history, and according to Vitruvius, they were used by ancient Greek and Roman builders. Surviving examples document their use in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Plans are still the most indispensable form of architectural notation.

=Elevations. An elevation is a representation of a facing of a building or part of one as if its features were projected onto a vertical plane that is parallel to the building. Elevations are effective for conveying proportions and details but poor at depicting curves and spatial relationships such as projection and recession unless shading is added.

The use of elevations is especially important for details, and the need for illustrations of moldings of the orders led to the popularity of Vignola's Regola, which was illustrated by elevations and plans.

●Sections. A section is an orthographic projection of a building as if it had been sliced through and one portion removed. Sections are usually taken vertically, and interior walls appear as elevations.

Combining Plans, Elevations, and Sections

Plans, elevations, and sections are most effective when presented together in the same scale and aligned so that their parts correspond.

=Maintaining uniform scale. In a memorandum to Pope Leo X in 1519, Raphael addressed the need for standardizing the representation of architecture by using plans, elevations, and sections in the same scale.

=Aligning projections. Corresponding parts of plans, elevations, and sections were generally aligned to make it easier to appreciate the correspondence between them. In I quattro libri, Andrea Palladio imposed a common scale and alignment for his two-picture presentations of plans with elevations and plans with elevation-and-section combinations. At times, plans and elevations were overlaid.

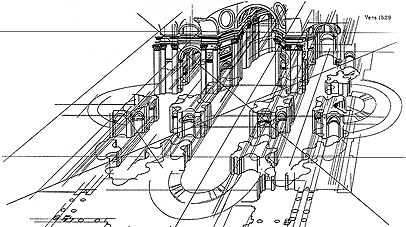

Constructions

A construction is a representation of a building that reveals the layers of its structure selectively. Constructions usually combine the cutaway aspect of a section with the realism of a perspective drawing.

Several architects explored graphic means of illustrating structural details. Giuliano da Sangallo developed a special form of construction that revealed the interiors of ancient buildings by depicting openings that resembled those left by deterioration. Leonardo da Vinci explored cutaway views for illustrating human anatomy.

Peruzzi, who had been trained as a painter and worked as a scenographer, created a construction of St. Peter's using linear perspective to illustrate a series of horizontal sections and vertical sections.

Constructions are useful to reveal interiors, simplify support systems, detail the relationships of parts, and separate the distinct stages of complex building procedures.

Media

Architects employed the same forms of media as artists. Typically charcoal, chalk, pen and ink, and wash were used. Although in paintings, architecture was usually in the background, it was occasionally the main subject as illustrated by View of an Ideal City and a series of lunettes showing Medici villas.

Architects who had been trained as artists often created highly effective illustrations.

|

Peruzzi's perspective view of a series of horizontal sections of Bramante's design for St. Peter's

Palladio's plan and elevation of the Villa Emo In the Renaissance, graphic means of representing buildings became more important because the architect's role became more nearly that of designer than construction supervisor. |

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back