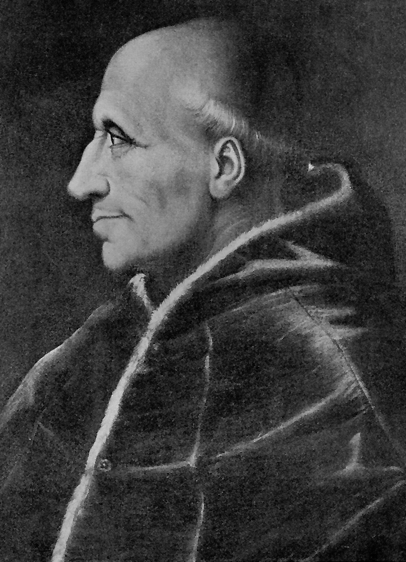

Hadrian VI

January 9, 1522 - September 14, 1523

PRE-PAPAL BACKGROUND

Birth in the Netherlands

Pope Hadrian VI (also Adrian VI) was born Adrian Florensz Dedal in Utrecht in 1459. He was the only pope from the Netherlands ever and the last non-Italian pope until the election of John Paul II (1978-2005) of Poland 455 years later.

Selection of the name "Hadrian"

Hadrian was one of only two popes in the last thousand years to take the name with which he was baptized as his papal name. (The other, Marcellus II, also lived in the sixteenth century.)

Academic Training and Career

Adrian's widowed mother, who struggled to provide a decent education for him, enrolled him with the Brothers of the Common Life.

Adrian was a gifted student but poor, and his university studies were subsidized by Margaret of Burgundy. In 1491, he took a doctorate in theology at Louvain University and became a professor there. In 1497, he became its chancellor.

Adrian's lectures were popular, and his first published work (1512) was a collection of lectures that his students had compiled and published on their own. His publication of Quaestiones quodlibeticae in 1521 was also well received.

Appointments

Adrian received a number of appointments both in the Church and the political realm.

●Tutor to Future Charles V. In 1507, Emperor Maximilian I appointed Adrian to tutor his grandson, the future Emperor Charles V.

●Co-Regent of Spain. After the death of King Ferdinand of Spain in 1516, Adrian served with Cardinal Jimenes as a co-Regent of Spain until Charles succeeded as King of Spain the following year.

●Bishop of Tortosa. Also in 1516, Adrian was named Bishop of Tortosa, a city in northeastern Spain near the Mediterranean coast.

●Inquisitor for Aragon and Navarre. Bishop Dedal, who believed that heretics should be prosecuted vigorously, became the Grand Inquisitor of Aragon and Navarre in 1516.

●Cardinal of Utrecht. At the request of King Charles of Spain, Pope Leo X created the position of Cardinal of Utrecht for Adrian in 1517.

●Inquisitor for Castile and Leon. In 1518 Cardinal Dedal was put in charge of the Inquisition in the regions of Castile and Leon, giving him control over the rest of Spain.

●Viceroy of Spain. While Charles was away from Spain (1520-22) after becoming emperor, Cardinal Dedal ruled in his place as Viceroy.

ELECTION AS POPE

Need for a Compromise Candidate

Hadrian, who was not in Rome for the conclave to elect Leo X's successor, was chosen as a compromise candidate to break a deadlock.

After Cardinal Giulio de' Medici realized that he did not have enough support to be elected, he supported Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who became a leading candidate. Before all parties reached agreement, the tide was turned against Farnese by arguments stressing his shady past. This included being imprisoned for forgery before his elevation to cardinal by Pope Alexander VI, who was having an affair with his sister, Julia Farnese.

Charles V's Influence

At a point when the cardinals had become frustrated with their lack of consensus and with being cooped up in the cold, dimly lit quarters of the Vatican Palace in winter, Cardinal Sisto Gara della Rovere read them a letter from Charles V, who recommended Cardinal Dedal and described his good qualities. Because of Charles' power as the emperor of the largest empire in European history, the cardinals were inclined to support his candidate in order to maintain positive relations with him.

Cardinal de' Medici, who controlled a faction of supporters, was brought to affirmation by a bribe from Cardinal della Rovere on behalf of the emperor. Through della Rovere, the emperor promised a 10,000-ducat pension and the emperor's support in the next papal election, which would probably not be too far off considering Cardinal Dedal's age (63) and health.

Lack of Familiarity with Nominee

Because Adrian was born in northeastern Europe and had never been to Italy, the cardinals were unfamiliar with him and soon regretted their choice.

Traveling to Italy by Ship

To maintain a neutral position in the sphere of international politics, the Pope-Elect refused the invitations of both King Francis I of France and Emperor Charles V to visit them on route to Italy. He underscored this by traveling from Spain to Rome by sea so that he would not have to travel through their territories.

FACTORS INFLUENCING UNPOPULARITY

Widespread Dislike of Hadrian VI

A number of factors contributed to Pope Hadrian VI's being disliked by both Italian Churchmen and the Roman public, who rejoiced at his death and erected a statue to his doctor, who was hailed as a liberator.

Foreign Extraction

There was substantial prejudice against Hadrian because he was not Italian, and his lack of Italian manners made him seem like a barbarian. Because Hadrian spoke no Italian, he spoke in Latin, but the Italians found Hadrian's Latin pronunciation difficult to understand.

Lack of Appreciation of Italian Art

Hadrian was shocked with some of the art he saw at the Vatican. He considered white-washing Michelangelo's ceiling of the Sistine Chapel because of its nudity and sensuality. He also frowned on ancient sculpture, which was represented at the Vatican by works like the Laocoön.

Asceticism

Hadrian's ascetic (austere and self-denying) nature put him at odds with a papal court accustomed to feasts, ceremonies, and the pursuit of pleasure.

He continued to live a Spartan life of early rising, simple food, and only a few servants. This behavior earned him a reputation for stinginess, and when he was dying, a group of cardinals demanded to know where he had hidden the funds he had saved by his penury.

Employment of Foreign Assistants

The mutual distrust between the pope and the cardinals was partly based on his employing foreign assistants like his friend Wilhelm Enckenvoert and not admitting any of the Italian cardinals into a personal relationship.

On his election as pope, he appointed Enckenvoert as the Bishop of Tortosa, and just before he died, he raised him to cardinal. This was Hadrian VI's only appointment of a cardinal.

Demand for Change

The principal source of friction between the pope and the Italian clergy was his call for changing church policies and limiting spending.

Lack of Tact

Hadrian's lack of tact and diplomatic skill was an important factor in his failure to influence either churchmen or foreign sovereigns.

REFORMING THE CHURCH

Reform to Combat Reformation

Hadrian attempted to deal with the beginning of the Reformation and Martin Luther's rising popularity by reforming the Church.

Admission of Curia's Failings

At the meeting of a German council at Nuremberg in December of 1522, the pope's representative acknowledged the Church's past abuses and blamed the Curia, its administrative branch.

Many historians consider this admission to have been the first step of the Counter Reformation, which was begun in earnest under Pope Paul III (1534-49).

Reform of Policies

Pope Hadrian VI attempted to reform the Curia, the administrative body of the Church, by eliminating simony (buying or selling church offices) and getting rid of many of the administration's secular members.

The pope would have liked to have ceased the Church's selling of indulgences but the Church was too far in debt to give up the income. Had he had the money to reimburse the cardinals for the bribes they paid for their positions, he would have taken away their existing benefices (income-producing appointments).

Reform of Spending Practices

To pay off the huge debts of his predecessor, Hadrian implemented drastic cuts in spending.

On his arrival in Rome, he stopped the construction of a triumphal arch that was being built in his honor. He halted construction and decoration at the Vatican Palace and elsewhere except for St. Peter's.

Although Hadrian did not commission any art, he did redeem the Raphael tapestries, which Leo X had pledged as security for one of his loans.

Most distressing for the cardinals was the pope's ceasing to hand out lucrative benefices. The system of benefices, in which an individual could hold many at the same time, led to the Church's administrative work being passed on to unqualified, poorly paid secular employees instead of being performed by the benefice holder.

Ineffectiveness of Hadrian's Reforms

Hadrian was unable to reform the Church because of both the shortness of his pontificate (twenty months) and the unwillingness of the cardinals and other adversely affected Church officials to implement his policies.

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Dealing with Luther's Revolt

In addition to attempting to combat Lutheranism by reforming the Church, Hadrian wanted to take action against Luther. Speaking through his representative at a Church council in Nuremberg, Hadrian demanded that the ruling from the council at Worms in 1521 be enacted with regard to punishing Luther for heresy and suppressing his preaching.

Policy of Neutrality

As underscored by his having come to Italy by sea, Hadrian wished to maintain neutrality in the conflict between Francis I and Charles V.

Charles V, who had been tutored by Adrian, had expected his support and was angry at not getting it as payback for having promoted his career by naming him Viceroy of Spain, asking Leo X to make him a cardinal, and writing a letter to the cardinals recommending him as pope.

Call for a Crusade

After Rhodes fell to the Turks in October of 1522, Hadrian tried to force Francis and Charles to join in a Crusade by imposing a three-year truce on their war, but they ignored his call.

The pope's pleas to other European leaders to join together in a Crusade also fell on deaf ears.

Conflict with Francis I

Through an interruption in the correspondence between King Francis and Cardinal Soderini, the pope learned that Francis I was planning to invade Italy. After the pope had Soderini arrested, the French broke off diplomatic relations and ceased sending Church revenue to Rome.

Because of the threat of an invasion by the French, the pope joined the emperor's alliance in August of 1523. Francis' subsequent invasion of Italy coincided with the pope's falling ill and dying.

DEATH AND BURIAL

Illness and Death

Exhausted by the recent political developments and not used to the heat of an Italian summer, Pope Hadrian VI became ill and died in September.

Burial and Re-burial

Hadrian VI was initially buried at St. Peter's in the Chapel of San Andrea. His placement between Pope Pius II and Pope Pius III prompted one of his detractors to deface his tomb with a joke about an impious pope being buried between two Piuses.

Ten years after his death, Hadrian's long-time friend Wilhelm Enkenvoert had him re-buried in a fine tomb to the right of the choir of Santa Maria dell'Anima, the Church of the German nation. The monument was designed by the Sienese architect and theater-set designer Baldassare Peruzzi and sculpted by the Florentine garden designer and sculptor Niccolô Tribolo.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back