Sant' Andrea

Mantua, designed 1470, begun 1472

Architect: Alberti

HISTORY

Commission

Ludovico Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua wished to build a larger church to replace Sant' Andrea, a small pilgrimage church that held the much-visited Relic of the Sacred Blood.

In 1470, when Ludovico was considering a plan by another architect, Alberti, who had designed San Sebastiano for him ten years earlier, submitted a plan. In a letter to Ludovico, he argued the superiority of his design in terms of construction cost and functionality. The expense of importing stone columns could be avoided by supporting the nave by pillars, whose cores could be built of brick. The access by pilgrims to the reliquary could be achieved more readily by having a wider nave.

Construction History

The building of Sant' Andrea commenced in 1472 after the old church had been torn down. Luca Fancelli, Ludovico's long-time architect, was in charge of the construction.

The church was completed from the entrance end as far as the crossing by 1494. Even though Alberti's death precluded his usual correspondence with the builder, Fancelli's construction was faithful to Alberti's design.

Construction continued in waves, and Sant' Andrea was not completed until the eighteenth century. Its final feature was the dome, which was built according to a design by the late-Baroque Italian architect Filippo Juvarra.

STRUCTURE

Vaulted Nave Ceiling

The construction of Sant' Andrea was entirely different from that of Brunelleschi's churches, which resemble Early Christian basilicas in having flat nave ceilings and columnar supports. (Flat nave ceilings were conjoined with the roof-trusses.)

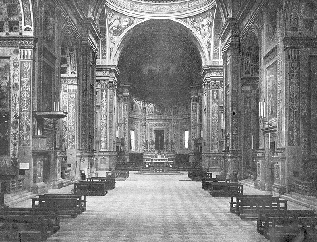

Alberti's Sant' Andrea, whose nave is 56-feet wide, follows Roman models in utilizing massive piers decorated by the orders and barrel-vaulted ceilings, which are painted with fictive coffers.

Similarity to Constantine's Basilica

As Alberti himself stated in a letter to Ludovico, he based the plan of Sant'Andrea on that of an Etruscan temple. He most likely looked to the ancient Roman Basilica of Constantine, whose plan largely coincides with Alberti's description of the Etruscan temple type in De re aedificatoria. Although the vaulting scheme of the Basilica of Constantine differs from that of Sant' Andrea in having a groin vault instead of a barrel vault for the nave ceiling, the two buildings are alike in having trios of barrel vaults flanking the nave at right angles.

Rhythmic Arrangement of Features

In using two pilasters per pier and incorporating such features as niches and doors between them to decorate the nave arcade, Alberti developed a more complex rhythm than was typical of arcade decoration during his time.

It anticipates Bramante's travata ritmica (literally "rhythmical truss"), a motif using a rhythmic alternation of features like columns and niches on sections of wall between arches. Bramante developed this combination at the Vatican on the upper level of the Belvedere Court. (The arches were later filled in.)

CHAPELS INSTEAD OF SIDE AISLES

Use of Chapels

The areas to the side of the nave, which are proportionately narrower than most side aisles, are devoted to a series of chapels. Using the areas to the sides of the nave for chapels instead of side aisles had a precedent in Michelozzo's conversion of the side aisles to chapels a quarter of a century earlier at the Church of the Santissima Annunziata.

Poor Visibility from Side Aisles

Alberti did not favor the use of side aisles because the line of columns or pillars supporting the nave ceiling compromised the view of the altar.

In the next century, the Council of Trent, also took this position when setting forth guidelines aimed at making churches more conducive to worship.

Large and Small Chapels

The three barrel-vaulted spaces on each side of the nave contain large chapels that are open to the nave but separated by a few steps.

The hollows in the nave piers, which extend to the exterior wall, contain small chapels with domed ceilings.

LIGHTING

Use of Indirect Light

Because clerestory windows, the main source of illumination in most churches, were not used, the lighting in Sant' Andrea is largely indirect. This was in accord with Alberti's belief that dim lighting was appropriate in holy places.

Sources of Light

Light enters the church from several sources.

●Dome windows. Light from the windows in the dome, which is the strongest source of light, focuses the worshipper's attention on the crossing.

●Chapel windows. Light from chapel windows offers little illumination due to their distance from the church center and their being shaded from direct light by nearby buildings.

●Rose window. Light from a rose window at the end of the nave is reduced to an indirect glow by the arched hood on the exterior.

FAÇADE

Hood

The arched hood, called the ombrellone, which extends out from the upper end of the nave, is not generally believed to have been part of Alberti's design because of its lack of relationship to the rest of the building.

Relationship with the Rest of the Church

The façade of Sant'Andrea does not conform to typical basilica façades because it does not cover the entire width and height of the entrance end of the church, due in part to the proximity of the campanile (1413), which limits the space. Instead, the façade is lower and narrower than the church proper and functions as an entrance porch that is attached to the main structure rather than forming a single front wall.

Perhaps Alberti had the Pantheon in mind when he designed the façade of Saint' Andrea, which also solved the problem of providing an entrance façade for a wider building by appending a porch and vestibule.

Roman Models

Because the façade was free from having to correspond to the basilica end in size and shape, Alberti could readily plan it along classical lines. Alberti's design for the façade combined two Roman forms, the triumphal arch and the temple front.

1.Triumphal Arch. Alberti's fondness for the triumphal-arch form was also manifest at the Malatesta Temple and Santa Maria Novella.

2.Temple Front. Alberti again utilized the pediment-on-columns form, which he had used on all three of his earlier churches, the Malatesta Temple, Santa Maria Novella, and San Sebastiano.

Dual Role of Pilasters and Entablature

The giant-order pilasters and the entablature above them belong to both the triumphal-arch and the temple-front forms.

Dual Scale of the Orders

In addition to the huge order defining the triumphal arch and temple front, there is a second system of the orders in a smaller scale. The interweaving of differently scaled systems of the orders became an important element in the architecture of Michelangelo and Palladio in the next century.

Correspondence between Façade and Interior

There are several ways in which the design of the façade corresponds to that of the interior despite its smaller scale.

●Barrel vault size. The height and width of the barrel vaults opening off the nave arcade is repeated by the central vault of the façade.

●Alternation of large and small openings. The alternation of large arched openings and small flat-topped openings that lead to the large and small chapels is repeated on the façade.

●Vertical organization. The division into three levels of the fronts of the nave piers is repeated on the side sections of the façade.

●Transverse barrel vaults. The arrangement of vaults in which secondary barrel vaults open off both sides of a central barrel vault at right angles is repeated on the exterior by the vaulting of the entrance façade.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back