Baths

DERIVATION FROM GREEK PRECEDENTS

Origin in the Greek Gymnasium

Like many Roman architectural forms, Roman baths originated with Greek baths, which were originally part of gymnasiums. Gymnasiums functioned not only as places for washing but also as places for social interaction and cultural events.

Early Greek Bathing Facilities

Early Greek bathing facilities included rows of marble basins that were filled with cold water.

Early tubs provided hip baths, which accommodated the bather in a sitting position while immersing only the hips and buttocks. Tubs increased in size to accommodate full immersion.

Water was heated in boilers attached to furnaces, whose fuel, either wood or charcoal, could be added from outside the structure. The popularity of hot bathing led to the development of neighborhood bathhouses, which were located outside the city walls.

ROMAN HEATING INNOVATIONS

Overview

The Romans pioneered a system of radiant heating in which heat is conducted by the floors and walls themselves, which were made of materials that would absorb and retain heat. The baths were heated by filling the spaces under the floor and in the wall with hot gases created by furnaces.

Hypocaust System under the Floor

Although rudimentary forms of floor heating were employed in ancient Greece as early as the fifth century BC, the earliest remains of a bath using the hypocaust system are the Stabian Baths at Pompeii, which date to the second century BC. The Greeks may have developed a similar system at about the same time.

The floor was formed of concrete, which retained heat well and conducted it evenly. It rested on a series of short pillars of around two to five feet tall, which created a space beneath the floor that was heated by furnaces.

Tubuli in Walls

By the first century AD, bathhouse walls were heated by a system of hollow channels formed by tubuli, box-like terracotta tiles that formed vertical channels when stacked. Side by side stacks of tubuli formed the cores of walls. Holes in the sides of the tubuli allowed the hot gases to circulate laterally as well.

The stacks were located just beyond the edge of the floor, where they could be filled by the hot gases of the hypocaust system. Like concrete, terracotta retained heat well and conducted it evenly.

MAJOR ROOMS

Development of a Temperature Sequence

Although Greek bathing facilities included areas of different temperatures, it was the Romans who introduced a three-stage sequence from hot to cold. Roman advances in heating technology facilitated the regulation of areas of different temperature.

Caldarium

The caldarium, the warmest of the main rooms, was heated by steam and contained one or more tubs of very hot water.

Both domes and barrel vaults were commonly used for caldariums.

Tepidarium

The tepidarium lacked pools and mainly functioned as a transitional space between the frigidarium and the caldarium.

While warming up in the tepidarium, bathers were massaged and anointed with oils.

Because more time was spent in this chamber than the others, it was usually the most well decorated part of the bathhouse.

Frigidarium

The frigidarium, the coolest of the rooms, contained pools of unheated water for a cold plunge.

The frigidarium at the Baths of Diocletian, now the transept of the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, was formed of three groin vaults. Because they rise above adjacent parts of the structure, clerestory windows could be used.

Large open-air swimming pools were located just beyond the frigidarium at imperial baths such as the Baths of Caracalla and the Baths of Diocletian.

Later Refinements--Sweat Rooms

As Roman engineers improved their technology, sweat rooms, which were hotter than the caldarium, were created. The sudatorium was a steam room filled with moist steam, and the laconicum was a dry-heated chamber similar to today's saunas.

THERMAE

Comparison with Balnea

Thermae were one of the two basic types of public bathhouses in ancient Rome, the other being balnea, which were earlier and more common. Thermae were large and built by Roman emperors, who wanted to entertain the populace while enhancing their own reputations. Balnea were small and built by businessmen for profit. In plan, thermae were generally symmetrical and balnea were generally asymmetrical.

Layout

As they evolved, thermae became increasingly symmetrical and reached full symmetry in the first century AD.

Essentially, the major bathing facilities that were used by men and women together such as the caldarium, tepidarium, frigidarium, and swimming pool, lay along the central axis. Personal facilities that were used by men and women separately such as dressing rooms, massage rooms, and latrines, lay along each side.

Multiple Facilities

The large thermae followed the communal tradition of the Greek gymnasium, which integrated athletic, cultural, and social facilities. These sumptuous complexes included sports fields and tracks, libraries, lecture halls, theaters, and gardens.

INFLUENCE ON LATER ARCHITECTURE

Renaissance

In the Renaissance, the use of massive coffered vaults of varied types, i.e. barrel vaults, domes, and apses, like those of the imperial baths, was adopted for many types of structures. Raphael employed vaults of several types at the Villa Madama. Churches like Alberti's Sant' Andrea, Bramante's St. Peter's, and Vignola's Il Gesù made significant use of barrel vaults, apses, and domes.

The large semicircular windows used at thermae such as the Baths of Caracalla and the Baths of Diocletian were used by Andrea Palladio at San Giorgio Maggiore. These windows are called thermal windows in reference to their origin at thermae or Diocletian windows in reference the Baths of Diocletian.

Modern Period

In the nineteenth century, massive coffered vaults and thermal windows were often used in the United States for public buildings. The largest of these were metropolitan train stations like New York City's Pennsylvania Station, which was torn down, and Grand Central Station, which was restored to its original condition at the end of the twentieth century.

EXAMPLES OF ROMAN BATHS

Imperial Baths in Rome

Private Bathing Facilities

Baths Outside of Rome

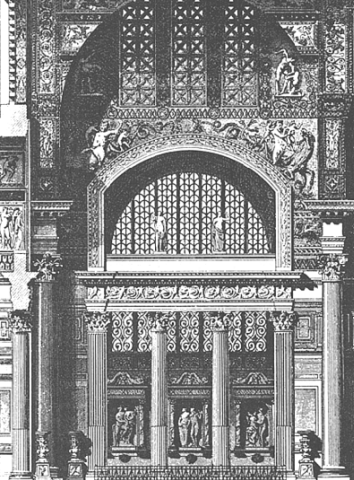

Restoration of Baths of Diocletian, Rome, c. 298-306

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back