Villa Barbaro

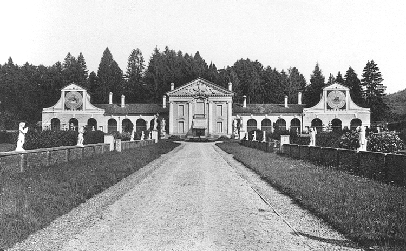

Maser, designed 1554-58

Architect: Palladio

PATRONS

Barbaro Brothers

The Barbaro brothers, Daniele and Marcantonio, commissioned Andrea Palladio to design the Villa Barbaro at Maser. Palladio had worked with Daniele from 1549 to 1556 preparing drawings for his annotated translation of Vitruvius' treatise.

Participation in Design and Decoration

The presence of many features that are not characteristic of Palladio's villas suggest that some aspects of the design and ornamentation were planned by the Barbaro brothers, who were themselves involved with architecture and sculpture. Daniele had studied architecture at a university and translated Vitruvius, and Marcantonio was an amateur sculptor.

INFLUENCE OF RECENT ROMAN VILLAS

Visits to Rome by Patrons

The brothers visited Rome many times and would have seen recent examples of the villa suburbana such as the Villa Giulia.

Terracing of Site

At the Villa Barbaro, the selection of a hillside site and the use of terracing to sculpt the land into a series of plateaus suggest the inspiration of sixteenth-century villas in Rome and the surrounding region.

The Villa Barbaro's site is so steep that the second story of the entrance side is level with the ground story on the rear.

Inclusion of a Nymphaeum

The inclusion of a nymphaeum, a feature that had been incorporated into many villas around Rome in both ancient and modern times, was probably inspired by contemporary Roman examples.

PLAN

Spread-Out Design

The main parts of the plan are a large block in the center, a wide loggia-fronted wing that stands behind the central block, and large blocks on each end of the lateral wing.

Two factors concerning the site conditioned the villa's lateral spread: the presence of foundations from an earlier laterally spread structure and the steepness of the slope, which would have required extensive excavation to accommodate a deeper building. These considerations also affected the disposition of rooms.

Entrance Block

The main reception room is a large cross-shaped hall that is located in the entrance block at the front.

Wings Containing Domestic Quarters

The plan of the villa is very unusual in that the wings, which usually contained utilitarian agricultural facilities, contained the residential suites. At most of Palladio's villas, the private apartments were massed with the reception rooms.

Four-room suites extend in a line on each side of the central hall. Enfilade doorways permit a nine-room vista from either end.

Central Hall at Intersection of Axes

At the intersection of the main and lateral axes, a central hall connects the domestic suites on each side to the cross-shaped hall at the front and to the courtyard containing the nymphaeum at the rear.

Loggias Extending to Each End

Loggias on each side of the center function as exterior hallways running the width of the building.

Service Blocks on the Ends

The large blocks on the ends contained service facilities such as the kitchen, storage rooms, stables, and dovecotes.

FAÇADE

Five-Part Organization

When seen from the front, a five-part symmetrical grouping is formed by the villa's main parts, which are easily distinguished by differences in height, roof, and features.

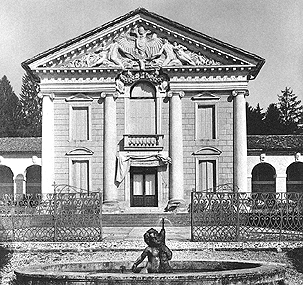

Temple Front on Central Block

The façade of the central block is articulated as a temple with colossal-order engaged columns of the ancient Roman Ionic order. Palladio modeled the columns after those of the Temple of Fortuna Virilus.

Treatment of Pediment

The intrusion of an arch into the pediment is a design Palladio may have copied from ancient Roman architecture. This motif is not found on his other villas.

The pediment contains emblems symbolizing the papacy, the Venetian state, and the Barbaro family.

Arcading of Wings

The arches of the wings are equal in size to those on the end blocks, creating continuity between these structures although the three arches on each end block are more widely spaced.

Sundials on Dovecotes

The upper portions of the two service blocks were used as a dovecotes, and their exteriors were detailed as sundials.

Atypical Stylistic Features

Several features of the façade are not typical of Palladio's villa design.

=Crowding of windows and pediment. The crowding of features such as the pediments of the upper windows and the architrave, which seem to touch, is uncharacteristic of Palladio.

=Ornate use of relief sculpture. Contrary to Palladio's usual Spartan use of ornament in pediments, which often contained no more than a family crest, the pediment of the Villa Barbaro contains a crowded grouping of large allegorical figures, emblems, and garlands, which spill out of the pediment through a break in the entablature.

=Lack of pedimented portico. The use of a pediment and columns as façade decoration rather than as the functional supports of a projecting portico was not characteristic of Palladio's villas.

=Use of curved screens on dovecotes. The use of curved screens extending outward below the pediments of the dovecotes is uncharacteristic of Palladio's design.

VERONESE'S FRESCOS

Illusionistic Character

The Villa Barbaro is one of Palladio's best-known villas on account of its trompe l'oeil fresco decoration by Paolo Veronese. His paintings cover its walls and ceilings with fictive architecture framing figures and scenes.

A few actual architectural features like cornices and door trim were added in stucco to heighten the illusion.

Subject Matter

Veronese's subject matter ranges from the real to the symbolic.

● Real people. Many figures represent members of the Barbaro family, their guests, and their household servants.

●Pastoral scenes. Landscape scenes portray an idealized world of man living in harmony with Nature. Fragments of ancient architecture allude to a bygone Classical past.

●Allegorical themes. Allegorical figures and scenes allude to themes such as the seasons and the planets. The barrel-vaulted ceiling of the central salone is painted to resemble a compartmentalized ceiling flanked by fictive balconies from which figures look down over balustrades. The central compartment contains Venus surrounded by figures symbolizing the Zodiac, an imaginary belt through the heavens that traces the sun's path over the period of a year. Gods personifying the Four Elements (Earth, Air, Fire, and Water) fill the corners, and figures symbolizing the Four Seasons occupy the rectangular compartments.

Palladio's Opinion of the Decoration

Palladio's failure to mention the Villa Barbaro's frescos in his discussion of it in I Quattro libri has been interpreted as his disapproval of the paintings.

As an architect, Palladio might well have been concerned about illusionistic paintings because they altered the architectural design of the walls they cover. Such paintings not only added solid features to the walls through the depiction of fictive columns, arches, and doors, but also subtracted parts of the walls themselves through the depiction of a space behind the wall plane.

In his treatise Palladio suggested that the choice of decoration was a matter of individual taste. It is easy to imagine that Palladio would have found it discrete to withhold his opinions about the tastes of his past, present, and potentially future patrons.

Main Features

The nymphaeum is semicircular in form and covered with relief ornament of stucco depicting cascading garlands, putti, emblems, and other classically inspired forms.

Statues of woodland nymphs occupy the apsidal niches, and statues of giants stand at the nymphaeum's outer corners and by the arched opening in the center, which leads to a grotto.

Water

The water in the circular pond originated in a mountain spring, from which it was channeled down to a reservoir serving the nymphaeum, the house, and the fields.

Inspiration

In view of the fact that none of Palladio's other villas included a nymphaeum, its use at the Villa Barbaro probably reflects the wishes of the Barbaro brothers.

Ancient descriptions of nymphaeums contributed to the popularity of this feature for contemporary Roman villas. On their visits to Rome, the brothers would certainly have seen Roman examples like the nymphaeum of the Villa Giulia.

Marcantonio's Contributions

The nymphaeum at the Villa Barbaro is believed to have been designed by Marcantonio Barbaro. Its copious use of relief sculpture is more indicative of his taste than of Palladio's.

Marcantonio, who was an amateur sculptor, may have made the four giants. (The stucco is attributed to Alessandro Vittoria or an artist of his circle.)

Background

In the late 1570s Palladio was called back to the villa to add a small church, which was intended to serve the local parish as well as the Barbaro family.

Centralized Design

This commission was Palladio's only opportunity to construct a central-plan church. Other earlier attempts to create a centralized church, at Il Redentore, for example, were denied and replaced with Latin-cross plans. Palladio considered the circle to be the ideal form, and this, like many of his predecessors, conceived of the central plan as the ideal structure. This preference is visible in the symmetry of many of his villas, particularly the Villa Rotonda, which is symmetrical on all four sides.

Similarity to the Pantheon

In addition to its popular name of Tempietto (Little Temple), this church has been called Piccolo Pantheon (Little Pantheon).

Like the ancient Pantheon in Rome, the Tempietto has a pedimented portico and a shallow, stepped dome that is hemispherical on the interior and rests on a circular exterior wall.

Although interrupted by three arms containing chapels, the circularity of the church's walls and dome still dominate the visitor's impression of the interior.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back