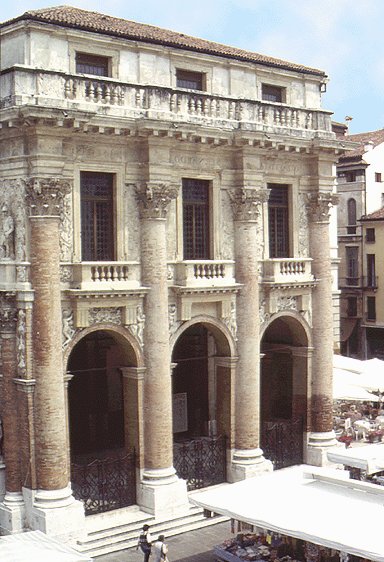

Loggia del Capitaniato

Piazza dei Signori, Vicenza, 1571-72

Architect: Palladio

BACKGROUND

Function

The Loggia del Capitaniato in Vicenza was designed by Andrea Palladio as an addition to the palace of the capitano, the Captain, who was appointed by the Venetian Republic to maintain order in the city.

The ground story functioned as a public loggia. The piano nobile, which had to be entered from the original palace, served as a meeting hall for the city council.

Patron

The capitano during the period of its construction was Giovanni Battista Bernardo, whose name is inscribed in the frieze. Bernardo, with the cooperation of the city council, was responsible for the Loggia and many other civic improvements that were made to Vicenza in the later sixteenth century.

The medieval palace and its one-story Renaissance loggia, which needed repair, suffered by comparison with Palladio's recent work on the Basilica, Vicenza's principal civic palace, which was located across the Piazza dei Signori.

Size

Experts disagree about whether the Loggia had originally been designed as a three-, five-, or seven-bay-wide structure.

GENERAL DESIGN

Description

The Loggia is a three-bay wide rectangular structure whose arcaded front is decorated by two-story columns. On the piano nobile, the windows and their individual balconies rest on brackets in the form of triglyphs. The balconies consist of sections of balustrade resting on lintels comprised of cornice-and-frieze sections. Another balustrade tops the entablature. The attic has plain square windows and simple pilaster trim above the columns.

The side that faces a side street is designed as a single arch flanked by solid bays and one-story high columns.

Use of Uncovered Brick

The brick used in constructing the arcade's piers and engaged columns was not covered by stucco, and its warm color produces a pleasing contrast to the lighter neutral tones of the stone trim and stucco relief.

Use of the Composite Order

The ornate quality of the composite order enables the columns to assert themselves despite the distraction offered by the relief-carved ornament decorating the wall areas. The plainer Tuscan and Ionic orders are used on the Basilica across the street.

Abundant Use of Relief

A dense pattern of stucco relief covers much of the available wall surface of the main two stories and adds to the Loggia's grandeur. This form of ornament is not typical of Palladio's work, in which ornament was derived from the orders and walls were defined by planes.

USE OF THE COLOSSAL ORDER

Late-Career Usage

The use of the colossal order, which is the Loggia's most striking feature, was part of Palladio's late style. Although he used two-story columns on villas from the 1550s, it was not until the 1560s that he used them on church façades and domestic palaces.

Use of Engaged Form

The Loggia's far more sculptural treatment of using half-round engaged columns instead of pilasters makes the columns, not the arches, seem to be the building's support system. These columns appear to be capable of supporting a substantial load rather than just the entablature and the balcony.

Visual Effects

The use of the colossal order had several advantages for the Loggia's appearance in relation to its site and function.

●Counterbalancing the Basilica. The Loggia's large scale and dramatic appearance, which resulted from the use of the colossal order, counterbalanced the Basilica's breadth and massiveness.

●Projecting dignified public image. The monumentality suggested by the use of the colossal order added dignity to the office of capitano and prestige to the city.

Absence of Secondary Order

Except on the right side, Palladio did not use a smaller, secondary order with the colossal order as he had at San Giorgio Maggiore and the Palazzo Valmarana and as his architectural predecessors who used the colossal order, Alberti and Michelangelo, had at Sant' Andrea and the Palazzo dei Conservatori, respectively.

Palladio's unexecuted design for the Palazzo Barbarano, which preceded his design for the Loggia, also used the colossal order without a secondary order.

MANNERIST FEATURES

Discontinuities

Several discontinuities compromise the clarity of the design of the Loggia and reflect the Mannerism that was still current in the Veneto.

●Discontinuity between facings. The front and right side do not match.

●Discontinuity of horizontal lines. The main horizontal features, the entablature and the string course, are interrupted by other features. The front plane of the entablature is broken by ressauts, and its architrave is pierced by the window tops. The string course, which consists of low-relief horizontal moldings that are aligned with the balcony moldings, is split into short sections by the windows and their individual balconies.

Merging of Stories

Without the use of a prominent horizontal member between the ground story and the piano nobile, a standard feature in sixteenth-century palace design in central and northern Italy, these two stories appear to merge in an arrangement reminiscent of Antonio da Sangallo the Elder's Palazzo Nobile-Tarugi.

As at Sangallo's palace, the walls of the main two stories of Palladio's Loggia are not distinguished from each other by a contrast between their surfaces, and because both stories are decorated by relief, they read as a continuous surface.

DESIGN OF LATERAL FAÇADE

Comparison with the Front

The loggia on the right side is different from its front. (The matching left side was only added in the early twentieth century.)

●Similarities. The lateral façade is similar to the front in having three bays articulated by engaged Composite-order columns and stucco-covered wall surfaces. These features help unify the two facings.

●Differences. The lateral façade differs from the front in having columns that are only one-story high, bays of two different sizes, and center-emphatic three-part compositions on both stories

Incorporation of Triumphal-Arch Motif

The Battle of Lepanto, which took place in 1571, the year the Loggia was begun, is commemorated by the side façade's triumphal arch shape and its allegorical sculpture program in which Victory and Peace occupy pedestals beside the main arch.

The battle, a great naval victory over the Ottoman Empire that was fought by a coalition of European forces, marked a turning point in stopping the advances of the Turks into Europe. Vicenza contributed money and two ships to the Venetian forces, whose fleet played a large role in the victory.

Reasons for Reducing Column Size

Not using colossal columns like those of the front on the lateral façade can be attributed to several aesthetic considerations.

●Lack of space. Because the lateral facing was narrower than the front, there would only have been sufficient room for two bays of the same size as the front ones, and the use of only two would have violated the classical design principle of centering a bay in the middle of a façade. If columns like those of the front were used with three narrower bays, the thickness of colossal columns would have been disproportionately large compared with the width of the intervals between them.

●Close viewing distance. The lateral façade faced on a side street from which the available viewing distance was short. Consequently, two-story columns would have seemed overly tall and out of scale with the surroundings.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back