Gonzaga Family

THE FAMILY

Three Centuries of Political Dominance

The Gonzaga family owned a great deal of land around Mantua. They gained control of the region politically in the 14th century, and their three centuries of rulership spanned the Renaissance and lasted into the 17th century.

Mantua's location on the Mincio River gave it strategic importance as well as attracting travelers and traders on route to the Mediterranean.

Working as Condottieri

The Gonzaga rulers supplemented their incomes by working as condottieri . They fought in many parts of northern Italy on behalf of many contenders for power, but most often they fought for Milan or Venice, the most powerful states in northern Italy.

Relationship with European Powers

The stability of the Gonzaga regime was partly based on the family's diplomatic skills, which included maintaining a strong relationship with the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire.

Gonzaga prestige is demonstrated by their marriages to the daughters of the ruling houses of Europe. In 1433, Barbara of Hohenzollern von Brandenburg (1422-81), the niece of Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, was married to Ludovico (later Ludovico II). And in 1531, Margherita Palaeologus, a descendent of the emperors of the Byzantine Empire, was married to Federico II.

In the Italy-wide conflicts between the popes and the emperors, the Gonzaga rulers often sided with the emperor. When this conflict erupted in the Sacking of Rome in 1527, Ferrante, a younger brother of Federico II, was one of the commanders leading imperial troops.

Relationship with the Church

Good diplomacy demanded a strong relationship with the Church. Ludovico persuaded Pius II to hold a Church council, which lasted ten months, in Mantua. He also arranged for his son Francesco to become a cardinal, an office that was held by many later members of the family as well.

Summary of Political Offices and Ranks

Rulers of the Gonzaga family enjoyed the rank first of capitano (1328-1433), next of marchese (1432-1530), and finally of duke (1530-1708).

●1328: Capitano. The Gonzaga family came to power when Ludovico I, at the age of sixty, was elected Capitano of Mantua. In Mantua, the capitano was elected by government councils, and its members were subject to political influence from powerful families. Ludovico expelled the former rulers, the Bonacolsi family, who had seized power in 1273 from the self-governing comune that existed earlier.

●1432: Marchese. Gianfrancesco Gonzaga bought the title of marchese from Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg in 1432. Gianfrancesco’s son, Ludovico, married Sigismund’s niece Barbara in the following year.

●1530: Duke. Federico II was granted the title of duke by Charles V. The title of duke was held by his descendants until 1627, when the main line of the Gonzaga family died out. A second branch of the Gonzaga family ruled until they died out in the next century.

PRE-RENAISSANCE PALACES AND CASTLES

Architecture Built by Francesco I

Francesco I (1382-1407) built two palaces during his period as capitano.

♦Casa Giocosa, Mantua, begun c.1388. Francesco commissioned the Casa Giocosa (House of Joy), a small palace that he used as a love nest. Later, it became famous as the home of a school established by Vittorino da Feltre under the sponsorship of Francesco's son, Gianfrancesco I. Francesco's grandson Ludovico was one of its pupils.

♦Castello San Giorgio, Mantua, begun 1395. The Castello di San Giorgio was begun in 1395 according to a four-tower design by Bartolino da Novara, who had just designed a similar four-tower castle, the Castello Estense, for the Este family in Ferrara.

Façade to Ducal Palace Complex

The complex of buildings making up the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua has grown through additions over the years.

GIANFRANCESCO I 1395-1444 (ruled 1407-44)

Titles

Gianfrancesco I was the fifth member of the Gonzaga family to hold the office of Capitano of Mantua. In 1432, Gianfrancesco paid Emperor Sigismund to grant him the hereditary title of Marchese of Mantua. Receipt of this official status ended the formality of elections and legitimized the family's right to rule in perpetuity.

Service as a Condottiere

To supplement his income from the state, Gianfrancesco worked as a condottiere. He served both Milan and Venice, who were constantly warring over control of the territory between them. Over the course of his military service, Gianfrancesco switched allegiances several times.

Marriage

Gianfrancesco married Paola Malatesta in 1409. Their union produced Ludovico II and five other children.

Dedication of Alberti's De Pictura

Between 1438 and 1444, Alberti dedicated a revised edition of his treatise on painting, De pictura, to Gianfrancesco.

Vittorino da Feltre's School

In 1423, Gianfrancesco made a significant contribution to the cultural success of the court of Mantua by inviting the prominent humanist and mathematician Vittorino da Feltre (1378-1446) to Mantua. Under Gianfrancesco's sponsorship, Vittorino established a school in La Casa Giocosa (House of Joy) at Mantua, the pleasure palace built by Gianfrancesco's father.

Vittorino's school educated the sons of the Gonzaga family, their courtiers, and other privileged families. Interested youth from poor families were also admitted, and at its peak, the school taught seventy students. It closed in 1446, soon after Vittorino's death, and two years after Gianfrancesco's death.

Vittorino's educational philosophy, which stressed the liberal arts, was modeled on Classical precepts concerning morality, style, proper social behavior, and physical fitness.

His students included Ludovico II Gonzaga and Federico II da Montefeltro. Their courts in Mantua and Urbino, respectively, were among the most culturally significant of the Renaissance despite the small size and relative unimportance of their marchesates.

Bequest for Annunziata Chancel

Gianfrancesco left 200 ducats to Santissima Annunziata in Florence for the construction of a circular chancel. His son Ludovico involved Alberti in the project, which was originally designed by Michelozzo.

LUDOVICO 1412-78 (ruled 1444-1478)

Political Background

Ludovico, who was the second Marchese of Mantua, ruled from 1444 to 1478.

In 1433 he married Barbara of Brandenburg, who was the niece of the emperor, Sigismund of Luxemburg, who ruled from 1410 to 1437.

As an astute politician, Ludovico managed to stay clear of war with his neighbors except as a condottiere fighting on behalf of whoever paid him. Although he fought for many different parties, he most often fought for the Sforza family.

Although the emperor Frederick III of Hapsburg (1440-93) never came to Mantua, Ludovico corresponded with him.

Relationship with the Church

Ludovico maintained a good relationship with a succession of popes.

He persuaded Pope Pius II to hold a Church congress in Mantua by promising that the emperor would attend. (The emperor did not.) The meeting of the papal court in Mantua began in 1459 and lasted eight months.

After the appointment of his son Francesco as a cardinal, Ludovico had an avenue of influence with the pope. This was especially useful when he was campaigning to transfer the Monastery of Sant' Andrea from the Benedictines to a foundation managed by his son. Authority over this monastery was especially desirable because it possessed the Relic of the Sacred Blood, a vial of Christ's blood, which attracted pilgrims and their gifts.

Urban Renewal

During the Church congress that took place in Mantua in 1459 and 1460, Pope Pius II and members of the papal court criticized Mantua's muddy streets and general appearance. This stimulated Ludovico to begin a campaign of upgrading the city. He paved the city center, rebuilt the market arcade, and added or rebuilt several churches and government buildings.

Education and Patronage

Ludovico's humanist education under Vittorino da Feltre made him one of the most cultured and enlightened patrons of the arts of his time. As revealed by his many surviving letters, Ludovico was actively involved in the planning and design of the projects he commissioned, and he brought many important artists and architects to Mantua to carry them out.

Employment of Pisanello

Soon after coming to power, Ludovico engaged the northern Italian painter and medallist Pisanello. Pisanello worked in Mantua a number of times during his career, and his works there are often difficult to date.

One of Pisanello's most remarkable Mantuan works is a fresco cycle illustrating scenes of War and Chivalry in the main reception hall of the Castello di San Giorgio, which is part of the ducal palace. It is unclear whether this unfinished work was begun before 1444, under Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, or after 1444, under his son Ludovico. In both its style and subject, the work exemplifies the International Gothic style, which was in fashion at most courts at the time.

Pisanello cast two portrait medals of members of the Gonzaga family. Both medals have busts on one side and equestrian portraits in armor on the other. Ludovico is known to have commissioned the one of himself around 1447, and it is believed that he commissioned the medal depicting his father, Gianfrancesco I, sometime after the latter's death in 1444.

Employment of Mantegna

In 1459 Ludovico employed the painter Mantegna, who remained in Mantua for nearly half a century and served Ludovico's son and grandson as well.

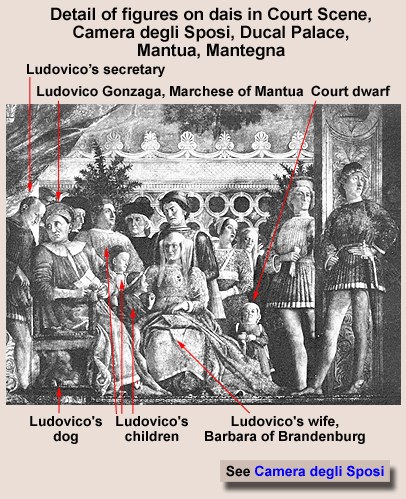

Mantegna's most important work for Ludovico was the Palazzo Ducale's audience chamber, the Camera Picta, which was later called the Camera degli Sposi, meaning the Bedroom (camera) of the Newlyweds.

The painting covers the ceiling and the two interior walls of one of the corner towers of the Castello di San Giorgio in the Palazzo Ducale. Although Mantegna was unable to paint away the ceiling's medieval rib-vaulting, he was able to cover it with fictive relief carving representing Roman ornament and featuring a series of portraits of Roman emperors framed by wreaths and ribbons.

Mantegna painted the room's walls to resemble a series of archways that reveal the open countryside in the distance. Set within this fictive architectural scheme are scenes of the Gonzaga family seated on the dais of an audience chamber and standing in an archway. References to hunting are made by a scene of servants holding dogs and a horse. Putti holding an inscribed plaque announce Ludovico's patronage.

At the center of the ceiling, Mantegna painted an extraordinary trompe l'oeil image representing figures looking over the parapet around an open oculus. Comic relief is provided by the putti playing in the parapet's openwork.

In the next few centuries, painted illusions of openings in the ceiling through which the sky and figures could be seen were repeated in the ceilings of churches, civic palaces, and villas.

Mantegna's naturalistic depiction of figures in a believable architectural and landscape setting presents a strong contrast with Pisanello's earlier International Style representation of an unstructured space filled with images of knights and chivalry.

Association with Alberti

During the course of the Church congress in Mantua in 1459-60, Ludovico became acquainted with Leon Battista Alberti, who had been in the pope's retinue.

Alberti supplied Ludovico with a design for San Sebastiano. A decade later, when Ludovico was planning to build a new Sant' Andrea to replace the older church, Alberti submitted a design and argued for its superiority over the plan that Ludovico was considering.

In not being a professional architect, Alberti's working methods differed from those of his contemporaries. Instead of supervising workmen on the site, Alberti communicated his ideas on paper. He prepared drawings of architectural details, and during construction, he maintained an active correspondence with both Ludovico and the on-site builder, Luca Fancelli, a stone-cutter from Florence.

Alberti introduced the idea that a different set of qualifications are needed by the designer than by the builder. It is a credit to patrons like Ludovico and his relative Sigismondo Malatesta that they accepted this revolutionary idea and entrusted Alberti with the design of their projects despite his lack of practical experience.

Contribution to Annunziata Chancel

Ludovico continued to support the building of a circular chancel, known as the Tribune, for Santissima Annunziata in Florence, for which his father left 200 ducats.

Ludovico Gonzaga became the patron of the tribune by 1449, and at some point, he involved Alberti in revising Michelozzo's original plans. Alberti may have redesigned the tribune in the early 1450s, but he was certainly involved after 1470.

The circular design was opposed by many Florentines because of its derivation from a pagan form like the cylindrical Roman mausoleum. Except for a few modifications, the chancel was carried out according to the circular plan designed by Michelozzo and modified by Alberti.

Churches Commissioned by Ludovico

In entrusting Alberti with the design of two important churches in Mantua, Ludovico was bold not only in utilizing an architect without practical experience but also in approving architectural plans that were new and innovative.

♦San Sebastiano, Mantua, 1460. San Sebastiano, Alberti's only centralized church, is the first church of the Renaissance to be based on a Greek-cross plan. Many of the building's proportions were based on the ratio of 3:5, which approximates the golden ratio. Two decades later, the church was completed under an architect who did not have Alberti's plan or understand classical design principles. Changes include a groin vault instead of a dome at the center and a dog-leg staircase on the side instead of a single wide flight at the front, as Alberti probably intended. It has been theorized that he also probably intended to have six, regularly spaced pilasters. During twentieth-century renovations, flights of stairs were extended forward from the side bays of the vestibule at the front.

♦Sant' Andrea, Mantua, 1470. Sant' Andrea is especially important for its use of chapels instead of side aisles to flank the nave, piers instead of columns to support the nave arcade, and a barrel vault instead of flat construction attached to the trusses to form the ceilings of the nave and choir. The façade, which is lower and narrower than the body of the church, functions as an entrance vestibule. Its design fuses a triumphal arch with a temple front and includes a second system of the orders. The façade and nave arcade correspond to each other in the sizes and shapes of their openings, the division of the vertical expanse into three levels, and the intersecting of large barrel vaults with small ones.

FRANCESCO II

1466-1519 (ruled 1484-1519)

Name and Lineage

Francesco II was the grandson of Ludovico and the son of Federico I, whose rule (1478-84) had been brief and undistinguished by any notable commissions in the arts.

Military Career

Francesco was very much involved in his military career and spent long periods away from Mantua while leading troops or being imprisoned by an enemy.

The high point of his career was the Battle of Fornovo in 1495. In this battle Francesco led Venetian forces to a partial victory against Charles VIII of France, who had led his army through Italy the year before.

Equestrian Interests

Francesco indulged his passion for horses by maintaining a large stable of horses that he used for racing, hunting, warfare, and breeding. Many of his race horses were champions, and his occasional gifts of horses to other princes were greatly valued.

Works Based on Roman Military Themes

Francesco's involvement with his work as a condottiere was expressed in his taste for art based on military themes, especially those associated with ancient Rome.

The terracotta portrait bust Francesco commissioned of himself around 1498 is Roman in form in being tapered at the base like ancient Roman busts rather than being flat at the bottom like Florentine busts.

Francesco may have commissioned Mantegna's celebrated nine-part series, the Triumphs of Caesar. The series includes scenes in which war trophies such as exotic animals are paraded through the city.

Works Based on Battle of Fornovo

The Battle of Fornovo became the theme of several of Francesco's commissions such as a prose epic describing the battle, an altarpiece showing Francesco as a kneeling donor offering prayers to the enthroned Madonna of Victory, and a scene illustrating Francesco commanding victorious forces. This last-named scene is part of a series of paintings celebrating the triumphs of the Gonzaga family.

FRANCESCO'S WIFE, ISABELLA D'ESTE

Francesco's Marriage to Isabella d'Este

Francesco was married to Isabella d'Este (1474-1539), who had been raised in the highly cultured Este family. Isabella's interests in the arts greatly exceeded that of her husband, whose absence due to his military career often left her in charge. Thanks to her, the Court of Mantua was among the most splendid courts in Italy at that time. After Francesco died of syphilis at the age of 53, she acted as an advisor to her eldest son, Federico II Gonzaga, who, at the age of 19, became the new Marchese of Mantua.

Isabella's Collecting

Isabella was one of the first important female patrons on record. As an avid collector of ancient art, she amassed a wide variety of valuable objects like ancient coins, cameos, and gemstones. She supplemented her collection of ancient sculpture by commissioning the contemporary bronze sculptor Antico to make copies of ancient statues in other collections.

Isabella also collected contemporary art, which she often bought from artists' estates through extensive correspondence.

Her failure to persuade Giovanni Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci to paint narratives for her was at least partly because she imposed a great many specifications concerning the figures such as their number, identity, scale, size, and relationship to the composition. Such matters had generally been left to the artists' discretion.

Isabella's Studiolo

To house her collections of contemporary and ancient art in her apartment in the Castello di San Giorgio, Isabella built a studiolo and a grotto beneath it. She commissioned five large allegorical paintings that were built into the paneling. These included Mantegna's Parnassus and Expulsion of the Vices, Perugino's Battle between Love and Chastity, and Lorenzo Costa's allegorical painting of Isabella, Triumph of Poetry.

In 1522, a few years after the death of her husband in 1519, Isabella moved her quarters, including her studiolo and grotto, to an older part of the palace complex so that her former quarters could be redecorated for the next marchesa, her son's future wife. Her new studiolo included a marble doorway and intarsia paneling. Two additional paintings by Correggio lightened the seriousness of the theme of virtue by adding a note of playful eroticism.

Isabella's Planning a Monument to Virgil

Isabella planned a monument to Mantua's most famous son, the Roman epic poet Virgil, but it was never executed.

Portrait of Isabella by Leonardo da Vinci

A painted portrait of Isabella d'Este, which had been stored in a Swiss vault since the beginning of the 20th century, came to light in 2013. Carbon testing dates the work to the early 16th century, and many experts believe that Leonardo painted it. The painting clearly corresponds to a drawing of Isabella that Leonardo made in 1499, when he went to Mantua after leaving Milan. At that time, Isabella asked Leonardo to make a painted version, but its existence has not been substantiated until recently. The work is now being examined to determine which parts of the painting were by Leonardo's own hand and which parts were by his assistants.

FEDERICO II

1500-40 (ruled 1519-40)

Federico's Court

As the son of Francesco II and Isabella d'Este, Federico II continued to operate a splendid court, whose number reached eight-hundred individuals. He twice entertained Emperor Charles V.

Marriage

In 1531 Federico married Margherita Palaeologus, who was a descendent of the emperors of the Byzantine Empire and who inherited the duchy of Monferrat. Because of her Greek ancestry, a fresco cycle by Giulio Romano illustrating the Trojan War in Mantua's Palazzo Ducale was presented from the Greek point of view expressed in Homer's Iliad rather than the Italian point of view expressed in Virgil's Aeneid.

Political Relationships

The rulers of the principal foreign powers in northern Italy during Federico's rule were Emperor Charles V and King Francis I of France, who were both young like Federico. Charles was the same age and came to power the same year as Federico, and Francis was six years older and came to power four years earlier.

Like most of the Gonzaga rulers, Federico fought as a condottiere. Early in his rule he joined Charles V's forces in a war to repel the French at Pavia.

Several Popes, notably Leo X, Clement VII, and Paul III, controlled the Papal States during Federico's rule.

In the mid-1520s, after Pope Clement VII allied himself with Francis I against Charles V, Federico sided with the emperor to the extent of letting imperial troops pass through his territory on their way to sack Rome. Federico's brother, Ferrante, was among Charles V's commanders.

Imperial Rewards

For his military aid against the French at Pavia and against the pope in Rome, Charles V awarded Federico the device of Mount Olympus in 1522 and the title of Duke of Mantua in 1530.

Charles also consented to Federico's marriage to Margherita Palaeologus, which brought him a second duchy.

Interests in Horses and Hunting

Federico, like his father, was passionately interested in horses and stabled hundreds of them at his villa at the edge of town, the Palazzo del Tè. His favorites were portrayed in the villa's Sala dei Cavalli.

Federico used the Palazzo del Tè as a lodge for falconry and hunting with dogs. He commissioned Giulio Romano to build a marble mausoleum for his favorite dog.

Federico's Tastes in Decoration

Federico probably developed a sensitivity for art and fine objects from his mother, Isabella d'Este.

When he was between the ages of ten and thirteen, Pope Julius II held him hostage at the Vatican, where he was exposed to some of the finest art produced in the High Renaissance. (The pope held Federico because he wished to be assured of his father's cooperation.)

Seeing fresco decoration at the Vatican by Raphael and Michelangelo pre-disposed Federico to like large-scale fresco decoration that included many muscular figures. This taste was later satisfied by his court painter, Giulio Romano, who had assisted Raphael at the Vatican and other places.

Commissioning and Collecting Paintings

Federico shared his mother's passion for acquiring high-quality art. Although he was unable to purchase any of the works of Michelangelo, he was able to obtain many important works by the leading artists of northern Italy.

♦Correggio. Federico commissioned Correggio, whose paintings were sensual and erotic, to paint a number of works based on mythology for his studiolo in the Ducal Palace and other places. As a gift for Charles V, Federico also commissioned Correggio to paint four scenes based on the erotic escapades of Jupiter, who assumed various disguises to avoid the notice of his wife while he seduced females. This group included Danaë, to whom he appeared as a shower of gold.

♦Titian. Federico maintained a friendship with Titian and commissioned many paintings from him including portraits like Federico with a pet dog. Federico also presented Titian to Charles V, who commissioned several portraits over the years.

Bringing Giulio Romano to Mantua

In 1524 Federico, who was following the recommendation of his cultural ambassador in Rome, Baldassare Castiglione, brought Giulio Romano, who had worked for Raphael in Rome, to Mantua to be his court painter and architect.

Giulio frescoed many rooms in Federico's palaces and villas including new apartments for both Federico and his wife at the Palazzo Ducale.

Giulio's Palazzo del Tè Frescoes

Giulio's most important frescoes are the ones he painted at the Palazzo del Tè. Because this was the duke's primary recreational structure, its decorations came closer to reflecting his personal tastes and interests than those painted in the Palazzo Ducale.

♦Sala dei Cavalli. The Duke's interest in horses is demonstrated by a series of equine portraits, which are presented illusionistically as if the horses were standing on a ledge within a sumptuous marble-encrusted, pilaster-trimmed room.

♦Sala di Psiche. The villa's social and amorous functions were underscored by sensual interpretations of scenes from mythology. At the wedding feast of Cupid and Psiche, for instance, the guests included amorous satyrs and woodland nymphs.

♦Sala di Gigante. In the Sala di Gigante, the gods are depicted in the act of expelling the rebellious giants. This room is dominated by images of crumbling rock structures and falling giants, which wipe out all reference to walls and corners. Moreover, the room is an echo chamber, adding the sensory element of sound to the total illusion.

Architectural Pursuits with Giulio Romano

Like his great grandfather Ludovico, Federico understood the value of architecture as a visual form of propaganda. While being held hostage by Julius II as a boy, he witnessed the launching of an architectural campaign to restore Rome to its ancient splendor.

As Giulio Romano continued to prove his merit in Mantua, Federico increased his responsibilities and rewards. He eventually put Giulio in charge of Mantua's program of urban renewal and remodeling important buildings.

♦Palazzo del Tè, Mantua, 1526-34. Giulio Romano designed the Palazzo del Tè, a villa suburbana just outside of Mantua, for Duke Federico II Gonzaga. The building consists of four equal wings forming a large square courtyard, which was originally planted as a maze. The exterior, which incorporated wide and narrow bays, was related to the courtyard by a similar vocabulary. The courtyard's four walls were designed so that facing walls follow the same pattern. At the centers of the courtyard walls are triple-arch portals on the north and south wings and pedimented portals on the east and west wings. The courtyard is often cited as an exemplar of Mannerism. The tightly packed arrangement of rusticated features stands in marked contrast to the openness and elegance of the garden façade although they have a similar arrangement of features. The garden façade's vocabulary of arches and supports approximates the configuration known as a Palladian motif. The decoration of the interior features frescoes by Giulio Romano.

♦Palazzo Ducale additions, Mantua. At the Palazzo Ducale, Federico commissioned Giulio to add the Estivale in 1539. This building and the Cortile della Cavallerizza (Riding School Courtyard) formed a viewing area and performance space for equestrian activities.

♦Mantua Cathedral renovation. After Federico's early death in 1540, his brother Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga, who was acting as regent for Federico's son, employed Giulio to renovate Mantua Cathedral and S. Benedetto in Po.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back