Medici Family

OVERVIEW

Early History

By the thirteenth century, the Medici family were in Tuscany, and by the beginning of the fifteenth century, they were well established under Giovanni di Bicci.

Medici Control of Florence

The Medici controlled Florence during most of the Renaissance. During much of the fifteenth century, Medici interests were preserved by a party of supporters who formed a majority in the Signoria, the governing council in Florence. In the sixteenth century, the Medici ruled directly as governors and dukes; their authority was instituted and backed by outside powers such as the pope and the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Medici family were expelled three times (1433-34, 1494-1512 and 1527-1530) during the Renaissance.

Ongoing Sites of Patronage

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the family church and palace were important sites of patronage.

♦San Lorenzo, Florence. The Medici family re-built and expanded the family church, which was part of the Monastery of San Lorenzo in Florence.

♦Medici Palace, Florence. The Palazzo Medici, which was built in the mid-fifteenth century for Cosimo the Elder, was an important model in the development of palaces in the Renaissance. The palace was an important site of art patronage, and new decorations and furnishings were needed after the two periods of exile.

Medici Family Crest

The principal device on the Medici coat of arms is a cluster of five to twelve balls, palle in Italian. These have been variously interpreted as coins in reference to the family banking business or as pills or oranges in reference to the profession of medicine, which is suggested by the meaning of their name, "doctors." The orange was connected with medicine through its name, mela medica, which means "medicinal apple." The Medici encouraged this connection, although there is no evidence that the family, who primarily worked as merchants and bankers, was ever involved in medicine.

The Medici coat of arms, which was displayed at patronage sites, became a familiar emblem around town.

Giovanni di Bicci

Giovanni di Bicci (1360-1429), under whom Medici power and influence increased dramatically, was well established in Florence as a man of means and political influence by the early fifteenth century.

He commissioned Brunelleschi to design a sacristy for use as a family chapel.

♦Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence. The Old Sacristy was one of the first structures in Italy to embody the new Renaissance style and the first of a succession of Renaissance chapels and churches to employ a centralized plan.

Giovanni di Bicci's Older Son's Descendants

Until 1537, the most important patrons of the Medici family were Giovanni di Bicci's older son, Cosimo the Elder (Cosimo il Vecchio), and his descendants. In the fifteenth century, this included Cosimo's son, Piero, and his grandson Lorenzo the Magnificent (Lorenzo il Magnifico).

In the next century, Lorenzo the Magnificent's son and nephew became popes, Leo X and Clement VII. They were generous patrons of the arts who made commissions in Florence, Rome, and many other places.

After the 1537 assassination of Clement VII's son Alessandro, who had been granted the hereditary title of duke by the emperor in 1532, the succession of Cosimo the Elder's line ended and passed to the descendants of his younger brother.

Giovanni di Bicci's Younger Son's Descendants

The first Medici ruler who descended from Giovanni di Bicci's younger son, Lorenzo, was Duke Cosimo I de' Medici (1519-74), who was empowered after the assassination of his distant cousin Alessandro. The title of Grand Duke of Tuscany was conferred on him by Pope Pius V in 1569, and members of the Medici family continued to rule as grand dukes until the early nineteenth century.

COSIMO THE ELDER

Achievement of Wealth and Power

Cosimo de' Medici (1389-1464), who is often called "Cosimo the Elder" to distinguish him from Cosimo I, dramatically expanded the banking fortune left by his father, Giovanni di Bicci, through financial skill and the foresight to seek markets in other parts of Italy and Europe. By the mid-fifteenth century, the Medici bank was the most prosperous business in all of Italy, and Cosimo was one of the richest men in Europe and the de facto ruler of Florence.

Political Background

Cosimo was banished from Florence in 1433 when the opposition party headed by the Albizzi family gained control of the Signoria. He spent the next year in exile in Padua and Venice before returning to Florence in 1434, after his supporters had regained political power. His return inaugurated a new era of Medici-dominated politics in Florence.

Linking Finance and Power

Part of Cosimo's success came from doing business with people who could benefit him in return. Cosimo's business favors were linked to his network of political support in Florence and other places.

In loaning Francesco Sforza funds to pay the troops needed to bring him to power in Milan, Cosimo benefited politically by having an ally to the north rather than an enemy, as the Visconti family had been. Although establishing a branch of the Medici bank in Milan had the potential to be a profitable venture, the bank lost money because the Sforza extended their loans, allowing the interest to become quite large, and ultimately much of the debt was not repaid. The bank was closed in 1478.

The bank and the Portinari Chapel at S.Eustorgio, which were commissioned by the bank manager in Milan, Pigello Portinari, show the influence of Cosimo's architect Michelozzo, but today, it is doubted that he designed them.

Designation of Pater Patriae

Cosimo's was buried in the crypt of the Old Sacristy in the family church of San Lorenzo. In front of the altar there is a porphyry slab inscribed with the words Pater Patriae, which may be translated "father of the state." This honorific was awarded posthumously by the Signoria on March 20, 1465.

Scale of Patronage

Cosimo's architectural patronage was on an unprecedented scale for a private individual. It rivaled that of contemporary dukes and guilds. Cosimo entrusted Michelozzo, his favorite architect, with many of his most important commissions.

Ecclesiastic Commissions

Much of Cosimo's patronage benefited churches and monasteries in Florence and the towns nearby. As Medici importance increased in the fifteenth century, Cosimo played an increasingly larger role in supporting the family church of San Lorenzo.

♦Decoration of Old Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence. Cosimo, along with his brother, Lorenzo, commissioned their father's tomb and the decoration of the Old Sacristy, which his father had commissioned Brunelleschi to design in 1418.

♦Church of San Lorenzo, Florence. In 1442 Cosimo agreed to become the sole patron of the enlarged church of San Lorenzo, which had been begun in the 1520s according to a design by Brunelleschi. Cosimo commissioned Fra Angelico to paint a new altarpiece that featured the Medici family's patron saints, the doctors Cosmas and Damian, in the company of the Virgin Mary and several important Dominican saints.

♦Monastery of San Marco, Florence, 1436-43. Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to rebuild the Monastery of San Marco, which is much admired for the design of the cloister and the library. Frescoes by Fra Angelico, whose settings echo the monastery's design, decorate the walls, including the monks' cells.

♦Church of Santissima Annunziata, Florence, 1444-45. Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to rebuild and enlarge the original Gothic church of Santissima Annunziata. This remodeling included the conversion of the side aisles to individual chapels and the addition of a new east-end chancel and a new entrance court called the Chiostrino dei Voti (Cloister of Vows).

Domestic Commissions

Cosimo built a new family palace and remodeled several family villas in the Tuscan countryside.

♦Palazzo Medici, Florence. Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to design a new ten-bay (later expanded) family palace, which served as a model for Renaissance palaces until the end of the fifteenth century. Its facing of cut stone was an extravagant feature for the time. Medici coats of arms were displayed on exterior corners, on windows, and in the courtyard. The presence of a chapel reflected Cosimo's power because domestic chapels required a special dispensation from the pope. The original decoration of the palace's interior, which included paintings by some of the most important artists in Florence at that time, was commissioned by Cosimo's son Piero.

♦Remodeling Medici Villa, Cafaggiolo. Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to restore several family villas, like that at Cafaggiolo, where he added antique features like a rusticated stone arch trimming the entrance.

Urban Commissions

♦Remodeling Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Cosimo commissioned Michelozzo to remodel the courtyard of the Palazzo Vecchio (then the Palazzo della Signoria). Its five stories were articulated as three, and it resembled the Palazzo Medici in style.

♦Medici Bank, Milan. The Medici bank in Milan was commissioned by Pigello Portinari, Cosimo's agent in Milan. Its ornate Gothic detail and carved features reflect northern taste. Although the attribution is doubted today, the bank may have been designed by Michelozzo.

Art Commissions

♦Donatello's David. Cosimo commissioned Donatello to make a bronze statue of David, which stood in the courtyard of the Medici Palace. As the first statue since antiquity to represent a male nude, this work is a landmark in the history of art.

PIERO THE GOUTY

Overview

Cosimo's oldest son, Piero, (1416-1469) was head of the family for only five years before he died of gout and lung disease. He is called "Piero the Gouty" to distinguish him from other family members named Piero.

Unpopularity

Piero's refusal to extend loans made by his father forced many businessmen out of business and led to his unpopularity. Consequently, there were several plots against him, which were unsuccessful.

Receipt of Filarete's Treatise

The architect Filarete sent a copy of his treatise, Trattato d'architettura, to Piero because he regarded him as a potential patron. Piero's copy is important today because it is considered to be the closest to the original of the surviving copies. In the Renaissance, Piero's copy was important because it was studied by his son Lorenzo and circulated among his friends and architectural acquaintances.

Patronage

Piero was the agent of many of Cosimo's commissions. On behalf of first his father and then himself, Piero commissioned the original decorations of the Palazzo Medici.

♦Gozzoli's Procession of the Magi. Piero commissioned Benozzo Gozzoli to paint the walls of the Medici chapel with the Procession of the Magi. This work embodies aspects of the International Gothic style, which stressed splendor rather than the new naturalism.

♦Pollaiuolo's Labors of Hercules. Piero commissioned the Pollaiuolo workshop to paint three canvases illustrating the Labors of Hercules. Although the canvases have disappeared, their basic appearance is known from small copies made by Pollaiuolo himself.

♦Uccello's Rout of San Romano. Around 1455, Piero commissioned Paolo Uccello to paint three scenes of the Rout of San Romano for the Medici palace. The scenes are now in three different museums.

♦Tabernacle and oratory, Santissima Annunziata, Florence. For the interior of the Church of the Santissima Annunziata, Piero commissioned Michelozzo to sculpt a marble tabernacle to enshrine the miraculous image of the Virgin, a painting, which, according to legend, had been begun by a monk in 1252 and finished by an angel. Piero also added a private chapel next to Michelozzo's altar canopy.

LORENZO THE MAGNIFICENT

Overview

Shortly before his death in 1469, Piero the Gouty passed the leadership of the Medici family to his oldest son, Lorenzo de' Medici (1449-92), who was only twenty.

Although Lorenzo was a strong ruler, the Medici family's dominance in Florentine politics did not go unchallenged. An attack instigated by the Pazzi family in 1478 against Lorenzo and his brother, Giuliano, left the latter dead. Although several families were involved, this episode is known as the Pazzi conspiracy.

Like his grandfather Cosimo the Elder and his father, Piero the Gouty, Lorenzo was a generous patron of the arts and an avid collector of antiquities.

The Name Il Magnifico

The appellation il magnifico is commonly used today to distinguish Lorenzo from the other members of the Medici family of the same name.

In his own day, il magnifico was a title of respect accorded governors, captains, or minor princes in general.

Humanism at Lorenzo's Court

Lorenzo's court included a number of humanists including Marsilio Ficino, who translated Plato's entire body of works from Greek to Latin, making many of them available to Italian scholars for the first time.

The Neoplatonic reconciliation of Platonism and Christianity was arguably at the heart of many works of literature and art created in Lorenzo de' Medici's circle. One of the artists whose work has been found to contain Neoplatonic themes is Botticelli. His painting Primavera, which can be interpreted along Neoplatonic lines, was found in the rooms of one of Lorenzo's second cousins.

Consequential Decisions

As head of the clan, Lorenzo's actions could have substantial consequences affecting the family's future. Two were of particular importance: in 1490 he brought the Dominican preacher Savonarola to Florence, and in 1492 he persuaded Pope Innocent VIII to make his son Giovanni a cardinal. Ironically, Savonarola gave voice to the anti-Medici sentiment that brought about the family's exile in 1494, and Giovanni, as a cardinal, engineered the family's return in 1512 by influencing Pope Julius II.

Giovanni was later elected Pope Leo X, which enabled him to spend considerable amounts on family projects and promote the career of his cousin Giulio, who also attained papal rank. As Pope Clement VII, Giulio increased the family's importance, attaining the hereditary title of duke for his son, Alessandro in 1532.

Lorenzo the Magnificent's importance in furthering the family's future prominence was recognized by his descendants' commissioning portraits of him such as the one Alessandro de' Medici commissioned Giorgio Vasari to paint in 1533.

Interest in Architecture

Lorenzo was one of the most astute, design-oriented patrons of architecture in the Renaissance. He communicated regularly with other princes, from whom he obtained plans of buildings that were relevant to his own projects and to whom he, in turn, gave plans as gifts.

From letters and other documents, it is clear that Lorenzo contributed significantly to the designs of projects with which he was involved.

Lorenzo studied the architectural treatises of Filarete and Alberti. He owned a manuscript of Filarete's Il trattato d'architettura, which the author had given his father. He passed it around to local architects like Giuliano da Sangallo and Giuliano da Maiano and allowed a few of his royal associates to have copies made.

As the newly printed chapters of Alberti's De re aedificatoria became available, Lorenzo eagerly read each. It has been suggested that the treatise's publication in Florence in 1485 was due to his instigation.

Lorenzo sometimes recommended architects to wealthy patrons with whom he corresponded. For instance, he was instrumental in Giuliano da Maiano's being employed in Naples (1485-90), where he worked for the son of King Ferdinand I, Alfonso, Duke of Calabria, who was later Alfonso II, King of Naples.

Patronage of Art

Lorenzo employed many artists such as Pollaiuolo, Ghirlandaio, Botticelli, and Mino da Fiesole.

Lorenzo invited the young Michelangelo into his court, and it was during his boyhood years at the Medici court that Michelangelo sculpted the Madonna of the Steps (1491) and the Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs (1492). The latter topic was probably suggested by Angelo Poliziano, one of the many humanists in Lorenzo's circle.

Architectural Commissions

Lorenzo is believed to have made suggestions for the designs of the structures he commissioned.

♦Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. Lorenzo engaged Giuliano da Sangallo to design the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. This villa was significant because it was the first whose basic design reflected classical styling. A number of innovations in villa design were introduced here such as a pedimented entrance, enfilade doorways, and a barrel-vaulted salone at the center. Compared with earlier villas, its styling was simpler, its scale was larger, and its shape was more horizontal. Several features were later added to its original form. The grounds were composed of both formal gardens and agriculturally productive fields. It has been difficult for historians to separate the input of Lorenzo and Giuliano da Sangallo on this project, which appears to be the result of a close collaboration between an intellectual patron with deep literary knowledge and a skilled architect with direct experience of ancient architecture.

♦Rebuilding Monastery of Santa Maria a San Gallo, Florence. Lorenzo commissioned the rebuilding of the Augustinian Monastery of Santa Maria a San Gallo from Giuliano da Sangallo in 1488. (It was destroyed in 1529.)

♦Via Laura Project, Florence. Lorenzo was involved in an ambitious scheme of urban development to create a new road, the Via Laura, to connect the church of the Annunziata with that of Cestello. The complete project was not carried out, but four new houses were constructed along the new street.

Influence on Non-Medici Projects

♦Lorenzo sat on the building committees of several important buildings, including the Palazzo Vecchio (then the Palazzo della Signoria), and he influenced the commissioning of other buildings as well.

♦Florence Cathedral façade. Lorenzo served on the committee that was convened in 1491 to choose a façade design for Florence Cathedral. (The Cathedral's original thirteenth-century façade design by Arnolfo di Cambio is known from a drawing made of a painting of it.) In the end, the selection decision was put off, and the cathedral did not receive a permanent façade until the nineteenth century.

♦Sacristy of Santo Spirito, Florence. Lorenzo was on the committee of Santo Spirito when Giuliano da Sangallo was commissioned to design the sacristy. The church's design was directly influenced by Lorenzo, who chose to implement a plan that called for three entrance doors, rather than the four doors designed by the original architect, Brunelleschi. The sacristy was located beside the church's nave. The octagonal space formed by the sacristy's eight walls is vaulted by an eight-section dome. The Sacristy's rectangular vestibule is vaulted by Giuliano's characteristic coffered barrel vault.

♦Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato. Although Lorenzo was not part of the building committee for Santa Maria delle Carceri in Prato, his influence was a decisive factor in the committee's choosing Giuliano da Sangallo after having chosen another architect for the commission. Sangallo's church, whose plan is a simple Greek cross, consists of four rectangular barrel-vaulted cross arms that project from a higher, dome-topped square block in the center. It embodies many of the features that Alberti had recommended in his treatise.

first EXPULSION AND RETURN, 1494-1512

Overthrow of Piero

Lorenzo's son Piero de' Medici, who ruled the city by controlling a major faction in the governing council, maintained power for only two years before being overthrown.

When the French forces approached Florence in 1494, Piero negotiated a disadvantageous treaty with King Charles VIII, which effectively surrendered Florence to the French. This incensed both the governing council and the populace, who rose up in rebellion against the Medici, driving Piero and his brother, Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici, from the city.

Influence of Savonarola

Savonarola, who had been outspoken in his criticism of the Medici, called King Charles the "the Sword of God." Under the French, Savonarola occupied a position of authority, and when they left, he was instrumental in organizing a new republican government whose governing body was the "Council of Five Hundred."

Savonarola's sermonizing about the Medici family's ostentatious display of material wealth added to the impetus to get rid of the Medici and reinstall a republican government.

Anti-Medici Sentiment

After the expulsion of the Medici family, the Medici coats of arms were removed from sites around the city, and the contents of the Medici Palace were looted during riots. Most of their possessions were auctioned in 1495, but some were moved to the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of government. Among them were two works by Donatello: David was moved from the Medici Palace courtyard to that of the Palazzo della Signoria, and Judith and Holofernes was moved from an earlier Medici family palace to a platform, known as the ringhiera, in front of the palace's façade. Both works were interpreted as the triumph of the weak against their oppressors, thanks to divine favor.

The Medici gardens were acquired by the Monastery of San Marco, where Savonarola was the prior.

1512 Return of Medici Family to Florence

The return of the Medici to Florence was brought about by Piero's brother Giovanni de' Medici. As an influential cardinal in Rome, he persuaded Pope Julius II to intercede militarily in Florentine politics after the French, who had supported the overthrow of the old Medici regime, were defeated at Ravenna in 1512.

The Medici family re-acquired much of their former property after their return.

Following their return, a succession of Medici family members ruled Florence as governors. After Julius II's death, Medici autonomy in Florence continued to be backed by papal power because both Giovanni and his cousin Giulio became popes, and except for Hadrian VI's twenty-month pontificate, they held the papal throne from 1513 to 1534.

GIOVANNI (POPE LEO X)

Overview

Giovanni de' Medici (1475-1521) was the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Thanks to his father's influence with Pope Alexander VI, Giovanni became a cardinal at the age of fourteen.

During the period of Medici exile, Giovanni traveled in Europe and established a power base in Rome, where he became a powerful cardinal. His image, along with those of Pope Julius II and Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, was included in a fresco that Raphael painted in 1511 in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican. Cardinal Giovanni's connection with Julius II enabled him to bring about his family's restoration to power in Florence in 1512, and following Julius' death in 1513, he was elected to the papal throne as Pope Leo X.

From his position of power in Rome, Leo ruled Florence through other family members. To improve the Medici family's image, he commissioned Machiavelli to write Florentine Histories, which emphasized the family's contributions to the city in the fifteenth century. The history, which was completed in 1525 under Pope Clement, was largely political and ended with the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1492.

Patronage in Florence and Nearby

Acting through agents and in conjunction with his cousin Giulio, who governed Florence after the death of Lorenzo the Younger in 1519, Leo X was involved in many of the Medici family's projects in Florence.

♦Windows in arches of Palazzo Medici. To increase the security and privacy of the Palazzo Medici, the arches of the ground-story arcade were filled in with solid walls containing windows designed by Michelangelo.

♦Façade of San Lorenzo. After visiting Florence as pope in 1515, Leo X decided to add a marble façade to San Lorenzo, and many architects, including Giuliano da Sangallo, Jacopo Sansovino, Baccio d’Agnolo, and Michelangelo, competed for the commission. In late 1516, the contract was awarded jointly to Michelangelo and Baccio d'Agnolo, a wood-carver and architect. Michelangelo's façade was greatly influenced by Giuliano's designs, which included such features as double columns, rounded niches, central pediments, and extensive sculptural decoration. A new contract was signed in 1518 with Michelangelo solely, but in 1520, the project was put aside in order to concentrate on a new Medici chapel.

♦Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo. Through his cousin Giulio, Leo X commissioned Michelangelo to design the Medici Chapel. The commission was occasioned by the death of Lorenzo the Younger in 1519. The chapel is also called the New Sacristy because it forms a mirror-image counterpart to Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy. The Medici Chapel is similar to the Old Sacristy in plan, the use of pendentives, and the use of materials, but it is different in having a coffered dome, rectangular windows, an attic story, a two-part scheme of stone trim, and many unusual forms.

♦Decoration of main reception rooms, Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. Important artists like Pontormo and Andrea del Sarto were commissioned to paint the main reception rooms of the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano with scenes illustrating Roman history. The chosen subjects paralleled the Medici family's own history. In del Sarto's Triumph of Caesar, for instance, Lorenzo the Magnificent, who had been presented with exotic animals by the Egyptian ambassador, is portrayed as Caesar receiving a similar tribute. The Florentine people, who resented the Medici for ending Florence's self-government, would have objected to the self-aggrandizement and imperial overtones of this subject matter.

Patronage in Rome

Pope Leo continued the Vatican projects begun by his predecessor, Julius II, and began a Villa near Rome. Most of the commissions were made by his cousin Giulio or other family members.

♦Sistine Chapel tapestries, Vatican Palace. In 1514 Pope Leo funded the creation of a series of tapestries designed by Raphael and depicting the Acts of the Apostles. The tapestries lined the lower part of the side walls of the Sistine Chapel.

♦Villa Madama. Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, acting for Leo X, commissioned Raphael to build the Villa Madama on the Monte Mario north of Rome in 1516. In being patterned after ancient Roman imperial villas, the Villa Madama was planned to include a Roman theater, a hippodrome, a fish pond, a nymphaeum, a circular courtyard, terraces, and several types of gardens. Of special significance to the evolution of villa layout was Raphael's Roman-inspired orientation of features according to the terrain. The use of the ground story for the main rooms created a close relationship between building and landscape. The most admired part is the garden loggia, whose decoration was carried out after Raphael's death in 1520. Paintings on the vaults were executed by Giulio Romano, and the stucco work was carried out by Giovanni da Udine.

♦Portraits of family members. Raphael was commissioned to paint individual portraits of Leo X and several other important members of the Medici family as well as a group portrait of the pope with two cousins, Pope Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de' Medici and Luigi de' Rossi.

GIULIO (POPE CLEMENT VII)

Overview

Giulio de' Medici (1478-1534) was the illegitimate son of Lorenzo the Magnificent's murdered brother, Giuliano.

Giulio benefited significantly from his cousin's election to the papal throne as Pope Leo X. First, he was appointed Archbishop of Florence, and later he was made a cardinal. In 1517 he became Pope Leo's Vice-Chancellor, and as such, he assisted him in managing finances and policy. Giulio acted as Governor of Florence from 1519, following the death of Lorenzo the Younger de' Medici, until 1523, when he was elected to the papacy as Pope Clement VII.

Clement VII's pontificate took place during very troubled times, and his failure to negotiate with Emperor Charles V led to the Sack of Rome.

Commissions in or near Florence

Giulio de' Medici commissioned a number of projects in Florence both on behalf of Leo X while he was serving as Florence's governor and on his own behalf after becoming pope.

♦Redecorating the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. Giulio commissioned the re-decoration of parts of the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano.

♦Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo. As pope, Giulio continued the Medici Chapel project, which he originally commissioned from Michelangelo in 1519 for Leo X. This provided the family church of San Lorenzo with another sacristy that would serve as a funerary chapel. Michelangelo's Medici Chapel effigies were important models in the development of seated tomb figures. They are unlike earlier tomb effigies because the artist was less interested in achieving likenesses than in creating transcendent figures who symbolize, according to art historian Erwin Panofski, the active and contemplative lives.

♦Laurentian Library, San Lorenzo. Although conceived by Giulio in 1519 as a repository of the Medici collection of manuscripts, which he had given to San Lorenzo, the Library was not begun until 1523. It consisted of a ground-story vestibule leading up to the second-story reading room. Giulio affected the design of the vestibule by ruling out the skylight Michelangelo had proposed as impractical to clean. He also chose to have a staircase that descended into the center of the room, leading the way in the development of monumental staircases. The unusual design of the walls and crowding of parts make the vestibule one of Michelangelo's most Mannerist designs.

Projects in Rome and at the Vatican

In Rome, Giulio concentrated on the Vatican projects and the Villa Madama.

♦Villa Madama, Rome. As pope, Giulio continued work on the Villa Madama, which had been designed by Raphael. He was especially interested in garden hydraulics, and many water features were planned. Water from mountain springs entered the garden through fountains in the retaining walls on the upper side of the parterre . From there, it flowed to other fountains as well as to the large fish pond on the terrace below the parterre. Expansive gardens had been planned, but both the main building and the grounds were less than half completed when construction stopped due to the Sack of Rome. The enemy's burning of much of the completed portion created a cloud of smoke that Pope Clement could see from his fortress in the Castel San Angelo, while the Vatican was under siege.

♦Vatican Projects. In Rome Pope Clement supported the ongoing Vatican projects of building St. Peter's and expanding and decorating the palace, where he ordered the completion of the Stanza di Constantino, the last room of the Raphael Stanze to be decorated. He initiated the commission for Michelangelo to paint the end wall of the Sistine Chapel; the original subject may have been the Resurrection rather than the Last Judgment, which Michelangelo painted during the administration of the next pope, Paul III.

second EXPULSION AND RETURN, 1527-37

Sack of Rome in 1527

During the Sack of Rome, Pope Clement VII took refuge in the Castel Sant' Angelo, which was besieged by the forces of Emperor Charles V. Because Medici rule in Florence was supported by papal power, Clement's loss of power provided the Florentine people with another opportunity to expel the Medici and re-establish a republican government.

Expulsion from Florence

The Medici family were exiled again, and Ippolito, Giulio's successor as governor of Florence, and Alessandro, Giulio's illegitimate son, fled the city. The Medici villa at Careggi was burned during the anti-Medici riots.

Imperial Support of Medici Rule in 1529

Two years later, the Medici pope and the emperor came to an accord: imperial forces would restore the Medici to power in Florence and their two families would be united by marriage when the emperor's daughter Margaret reached a marriageable age.

Alessandro as Governor and Duke

Imperial forces besieged Florence until the city surrendered in August 1530, eleven months later. Pope Clement VII's illegitimate son, Alessandro de' Medici, was made governor of Florence. Imperial troops remained to occupy the city, which assured that the emperor would ultimately have control.

In 1532, Charles V made Alessandro the Duke of Florence.

Catherine de' Medici Marries French Royalty

Ever mistrustful of the emperor, Clement VII arranged a marital alliance with France to tie himself to Francis I through the marriage of his cousin Piero's granddaughter, Catherine de' Medici, to the king's second son, Henry. In 1533, the pope traveled to Marseilles for the wedding and an opportunity to meet with King Francis. Catherine became queen consort while Henry ruled (1547-1559), and after his death, she influenced French policy both as a regent and an advisor to her sons.

Marriage to Emperor's Daughter

Part of the deal between the pope and the emperor provided that the pope's illegitimate son Alessandro marry the emperor's illegitimate daughter, Margaret of Austria (1522-86), who was later known as Margaret of Parma. Because she was only seven in 1529, the marriage did not take place until 1536, when she was fourteen.

Alessandro's Assassination

In 1537 Alessandro was murdered by a distant cousin, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, who had expected to trigger an uprising and a return to republican government in Florence.

Alessandro's Patronage

While a duke, Alessandro commissioned Vasari to paint portraits of himself and some of his most prominent relatives, such as his great uncle Lorenzo the Magnificent.

COSIMO I'S LIFE

Lineage

Cosimo de' Medici was descended from Giovanni di Bicci on both sides of his family. His mother, Maria Salviati, was a great great granddaughter of Cosimo the Elder, Giovanni di Bicci's older son. Cosimo's father, Giovanni della Bande Nere, was the great-grandson of Giovanni di Bicci's younger son, Lorenzo. Consequently, Cosimo was Giovanni di Bicci's great, great, great grandson through his mother's side and his great, great grandson through his father's. Among Cosimo's other important ancestors are his paternal grandmother, Caterina Sforza, whose father and grandfather had ruled Milan as dukes.

Although he had Medici blood from both parents, Cosimo was not predestined to lead the family. He was a member of the ruling Medici line through his mother, while his lineage through his father, technically the one that would determine his social status, was from the secondary Medici line. Cosimo's rise to power was due to the 1537 extinction of the main Medici line, and it took some time for his sole authority to be accepted.

Events

1537: Rise to Power. After the assassination of Alessandro de' Medici, influential Florentines selected his distant cousin Cosimo to succeed him as Duke of Florence. As the first Cosimo de' Medici to hold the rank of duke, he is known as Cosimo I. Cosimo, who was only seventeen, signed a power-sharing agreement that he later disregarded.

1539: Marriage to Eleanor of Toledo. In 1539, Cosimo married Eleanor of Toledo, who was the daughter of Charles V's Viceroy in Naples. From all accounts, he was faithful to her, unlike most of his peers, who kept mistresses. She had eleven children.

1540: Moving to Florence's Civic Palace. In 1540 Cosimo and Eleanor moved from the Palazzo Medici to the Palazzo della Signoria, which then became was known as the Palazzo Ducale. (The building acquired its present name of Palazzo Vecchio, meaning "Old Palace," after the ducal family moved to the Pitti Palace.) Because this building was the real and symbolic seat of Florentine government when Cosimo took up residence there, it reinforced his role as the sole power in the new government.

1549: Purchase of Palazzo Pitti. In 1549, Eleanor used her dowry to purchase the Palazzo Pitti, the largest domestic palace in Florence, and Cosimo bought a large tract of land behind it. They engaged Nicolò Tribolo to design a garden behind the palace where they could pursue their interest in horticulture.

1550: Moving to Palazzo Pitti. In 1550 Cosimo and Eleanor moved permanently to the Palazzo Pitti. At that point the Palazzo Ducale was re-named the Palazzo Vecchio and used only for government activities. In 1564 Cosimo commissioned Vasari to build a passage connecting the two buildings, which is known today as the "Vasari corridor."

1554: Conquest of Siena. In 1554, Cosimo completed his domination of Tuscany with the conquest of Siena at the battle of Marciano.

1562: Death of Eleanor. Cosimo's wife, Eleanor of Toledo, died in 1562 when she was around 43. A recent exhumation and autopsy of her remains has revealed that she had a severe calcium deficiency and bad teeth, and that her death and that of two of her sons, was caused by malaria.

1564: Abdication. In 1564 Cosimo, who had ruled for 27 years, abdicated in favor of his eldest son, Francesco.

1569: Grand-Ducal Status. In 1569, Pius V granted Cosimo the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany. Emperor Maxmilian II, who felt that the pope had overstepped his authority in granting the title, later affirmed Cosimo's Grand-Ducal status.

1574: Death. After remarrying in 1574, Cosimo died at the age of 55. A recent exhumation and autopsy of his remains has revealed that three of the vertebrae of his spine had become fused in his later years, which caused him much pain.

Rulership

Cosimo was an effective and competent leader who was able to deal with a vast array of details. His authoritarianism was made clear from his first year as the Duke of Florence when he defeated a rebel army and executed its leaders, largely exiled Florentines.

COSIMO I'S ELEVATING FAMILY'S STATUS

Changing Family Reputation

Cosimo, who aspired to equality with the rulers of Europe, used his vast wealth to create an image of himself as not only rich and powerful but also noble by birth. The family history was mythologized accordingly.

The family's achievement of wealth through banking and other commercial enterprises in the previous century was downplayed. Instead, emphasis was placed on their civic contributions and patronage.

The success of Cosimo's efforts to attain equality with the European nobility would seem to be confirmed by his elder son's marriage to Joanna of Austria, the sister of Maximilian II, Charles V's successor as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

●New symbolic imagery. Cosimo's astrological sign, the Capricorn, replaced the traditional circular devices as the dominant image referring to the Medici family. The circular forms are thought to represent either the coins of a banker or the pills or oranges (called "medicinal apples") associated with a doctor. Emphasis was also placed on the crown and French fleur d'lis emblems that had been incorporated on the coat of arms after the marriage of Catherine de' Medici to the French king's second son in 1533.

●Courtly presentation in portraits. In portraits, the Medici were portrayed in ways that reflected their ducal status and political roles. In a pair of portraits by Bronzino, Eleanor wears a jewel-studded dress and Cosimo wears a suit of armor.

●Direct portrayal of family history. In narrative scenes, family history was depicted directly rather than in the allegorical guise seen in the scenes commissioned by Leo X and Clement VII at the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano, where events in Medici history were merely alluded to through analogous Roman events. Direct portrayal was generally associated with dynastic royalty and would have been offensive to Florentines, who had been proud of their republican heritage.

●Emphasis on pomp and splendor. Events like weddings or visits from royalty were treated with great pomp. Special decoration and courtly events added to the splendor of ceremonial processions and banquets. For example, when Cosimo's son Ferdinando married Christine of Lorraine in 1589, the celebrations included a simulated sea battle in the flooded courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti. In 1608, a larger sea battle was simulated on the Arno when Ferdinando's son Cosimo II married Maria Maddalena of Austria.

Stressing Family's Involvement as Patrons

Emphasis was placed on the family's importance as patrons. Like the nobility, the Medici were able to buy the finest of everything, to initiate projects, and to promote the careers of favored artists and architects. As patrons, they were portrayed as not only bountiful but also astute, discriminating, and much involved with the planning of works they commissioned.

●Sympathetic portrayal in Vasari's Lives. Vasari's Lives, which was sponsored by the Medici through their patronage of Vasari as both a painter and an architect, presented a positive image of the Medici that stressed their good judgment as patrons. The first edition, published in 1550, was dedicated to Cosimo de' Medici.

●Collecting. Cosimo collected rare and valuable items, which enabled him to display both wealth and taste. Portraits were among the things he collected, and he owned over three hundred.

●Establishing Accademia del Disegno. Cosimo encouraged the foundation of the Accademia del Disegno (Design Academy) by Giorgio Vasari in 1563, in part to identify himself with support for the arts.

COSIMO I'S PATRONAGE

Scale and Types of Commissions

Cosimo I commissioned works of art and architecture on a scale that paralleled the patronage of foreign royalty or the popes, making Florence one of the great cultural centers of Europe during the second half of the sixteenth century. Most of Cosimo's commissions concerned his home church, his residences, and his government headquarters.

Commissions at San Lorenzo in Florence

At the family church of San Lorenzo, Cosimo commissioned both new projects and the completion of projects that had been begun by Michelangelo in the 1520s under Leo X and Clement VII.

♦Finishing the Medici Chapel. After attempting to get Michelangelo to return to Florence, in 1545 Cosimo commissioned the master's former assistants to install the sculpture he had carved for the Medici Chapel. The Chapel contained the tombs of two of Cosimo's predecessors as rulers of Florence, his great uncle Giuliano and his distant cousin Lorenzo the Younger.

♦Finishing the Laurentian Library. Cosimo resumed work on the Laurentian Library, where the Medici collection of manuscripts was to be housed. By the middle of the century, the floor and ceiling of the reading room were in place. For the design of the staircase in the vestibule, Vasari was instrumental in getting Michelangelo to send a clay model to its current architect, Ammannati. The Library was opened in 1571 although the articulation of the upper wall of the vestibule was not complete.

♦Tomb of Giovanni delle Bande Nere. To honor his father, a military officer who died in battle while serving Clement VII, Cosimo commissioned a chapel for his tomb. It was located in the main church of San Lorenzo. The sculptor Bandinelli and the painters Pontormo and Bronzino were involved in the project, which was not completed as planned.

♦Planning Third Sacristy. Cosimo planned a new chapel, which was not built until the rule of his second son, Ferdinando.

Other Ecclesiastic Commissions

♦Counter-Reformation Church Remodeling. Cosimo commissioned the remodeling of the interiors of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella to bring these churches in line with the recommendations of the Council of Trent, which stressed making the altar visible from the nave. Papal gratitude for this contribution to the cause of church reform in Florence was expressed by Pope Pius V's conferring the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany to Cosimo I in 1569. Desire for papal favor had probably motivated Cosimo's church remodeling in the first place.

♦Promotion of the Cult of the Miraculous Image of the Virgin. Cosimo promoted a popular attraction for pilgrims, the cult of the Miraculous Image of the Virgin, a painting in Santissima Annunziata, which, according to legend, had been begun by a monk in 1290 and finished by an angel.

Domestic Commissions

♦Remodeling and Expanding the Palazzo Ducale. After moving to the Palazzo Ducale, Cosimo engaged Vasari, Bandinelli, and others to redecorate the formal reception halls and apartments for himself and his wife. The most important of the formal areas were the Hall of the Five Hundred and the Quarters of Leo X. In the Hall of the Five Hundred (Salone de Cinquecento), the place of honor on the podium at one end was given to Michelangelo's Victory, which was acquired from the artist's family after his death in 1564. The quarters of Leo X consist of six rooms that were each dedicated to an important member of the Medici family: Cosimo the Elder, Lorenzo the Magnificent, Leo X , Clement VII, Cosimo I's father, and Cosimo I. These rooms contained many portraits depicting illustrious members of the Medici family and scenes of Medici deeds. Cosimo remodeled the courtyard as well. He moved Verrocchio's statue of a Putto with Dolphin from the Villa Medici at Careggi to the courtyard's center. In preparation for the 1565 wedding of his oldest son, Francesco, Cosimo commissioned Vasari to redecorate the courtyard by adding stucco relief to the columns and fresco paintings to the vaults and walls. The walls featured scenes depicting Austrian cities, which were intended to please the bride, who was from Austria.

♦Expanding Palazzo Pitti, 1550-62. In the mid-sixteenth century, Eleonora of Toledo purchased the Palazzo Pitti, a very large palace that was originally built for Luca Pitti. Cosimo purchased a large tract of land behind it. The Medici commissioned Ammannati to expand the palace with wings forming a courtyard that faced a long upward view of the Boboli Gardens behind the palace. The gardens were ornamented by fountains, sculptures, and terraces, executed largely by Tribolo and Buontalenti.

♦Vasari Corridor. In 1564 Cosimo commissioned Vasari to design a corridor connecting the Palazzo Vecchio with the Pitti Palace, which was located across the Arno. The corridor ran over the street, through the Uffizi, above pedestrian walkways along the embankment, across the Ponte Vecchio, and through or beside structures between the bridge and palace. Butcher markets occupied the bridge's street-level until Cosimo's son Ferdinando, who found their smell offensive, installed goldsmiths shops instead.

♦Rebuilding and Redecorating Villa at Castello. In 1538, Cosimo I commissioned the artist and landscape designer Nicolò Tribolo to expand the Villa Medici at Castello and add a garden. It was planned according to a scheme by the historian Benedetto Varchi and was the first garden to be based on an elaborate iconographical program. Tribolo died in 1550, and construction was turned over to Ammannati. Like most Renaissance gardens, the parterre is subdivided geometrically into four-part compartments. Neither of the two fountains made by Tribolo remains intact at Castello. The whole Fountain of Venus was moved to the nearby Villa Medici della Petraia, and the statue of Hercules crushing Antaeus from the Fountain of Hercules has been moved to a museum.

Civic Commissions

♦Uffizi Palace. Cosimo centralized the administration of the government by concentrating all its agencies, which were scattered throughout Florence, at the Uffizi. Vasari created a single huge U-shaped structure from a group of buildings. It was located off the Piazza della Signoria next to the Palazzo Vecchio. The Uffizi, which consolidated Florence's various government offices in one building, has been seen as one of the first examples of architecture used to express the structure of absolutist government. This building is now a museum whose collection of Italian art is one of the finest in the world. Vasari also painted part of its decoration.

Sculpture

♦Neptune Fountain. Cosimo commissioned Ammannati to make the Neptune Fountain for the Piazza della Signoria.

♦Statue of Cosimo's Father. Cosimo commissioned Baccio Bandinelli to sculpt a marble statue of his father, which was placed in the Ducal Palace. It was moved to a corner of the Piazza San Marco in Florence in the nineteenth century.

COSIMO'S sons' patronage

Overview

Cosimo was succeeded by his eldest son, Francesco (1541-87), whose baptism is the subject of a painting by Vasari. Francesco died without a male heir in 1587 and was succeeded by his brother, Ferdinando (1549-1609), who resigned his cardinalate. Both brothers commissioned many works of art and architecture that enhanced both their own and the Medici family's prestige.

Francesco I's Patronage (ruled 1574-87)

The focus of Francesco's patronage was the city's civic center, the Piazza della Signoria, and the buildings in the vicinity, the Palazzo Vecchio, the Loggia dei Lanzi, and the Uffizi Palace.

♦Giambologna's Rape of a Sabine Woman, 1579-82. For the Loggia dei Lanzi, Francesco commissioned Giambologna to sculpt the Rape of a Sabine Woman.

♦Remodeling of the Palazzo Vecchio. At the Palazzo Vecchio, Francesco completed the remodeling of the Salone dei Cinquecento, which had been begun by his father. He also commissioned an elaborate studiolo for himself.

♦Tribuna of Uffizi Palace. Francesco commissioned Buontalenti, who was involved in the building's completion after Vasari's death in 1574, to design the Tribuna, an octagonal salone in the east wing of the Uffizi Palace.

♦Completion of Decoration at Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. At the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano, Francesco completed the decoration that had been begun under Pope Leo X.

♦New Villa at Pratolino. Francesco commissioned Buontalenti to design a new villa at Pratolino. Its sculpture included an Apennine figure by Giambologna.

♦Roof garden on Loggia dei Lanzi. Francesco commissioned a roof garden on the Loggia dei Lanzi.

♦Fountains at the Boboli Gardens, Florence. Francesco added several fountains at the Pitti Palace including one featuring a nude statue of his father's favorite dwarf, Morgante, riding a giant turtle.

Ferdinando I's Patronage (ruled 1587-1609)

By the late sixteenth century the Medici were firmly established as the hereditary rulers of Florence, and under Ferdinando I, the focus of family portrayal shifted from the earlier Medici ancestors to Cosimo I and his successors.

♦Villa Medici, Rome. While still living in Rome as a cardinal, Ferdinando bought and expanded a villa and its gardens on the Pincian Hill in northern Rome.

♦Cappella dei Principi, San Lorenzo, Florence, 1604-1737. For the family church of San Lorenzo, Ferdinando began a new funerary chapel, which would include his own tomb. It had been planned by his father and was much larger than the sacristies designed by Brunelleschi and Michelangelo. It was not completed until the eighteenth century.

♦Gardens at Villa Medici della Petraia. At the Villa Medici della Petraia, which is near Florence, Ferdinando engaged Bernardo Buontalenti to expand the casino and build a garden. The garden is laid out as a series of terraces descending the hillside. The terraces are planted in a series of rectangular beds on each side of a central allée. A fish pond filled with large carp is located between two staircases. In the eighteenth century, the fountain of Venus, which was made by Nicolò Tribolo, was brought from its original location at the Villa Medici at Castello.

♦Equestrian monument to Cosimo I, Piazza della Signoria, Florence. Ferdinando commissioned Giambologna to cast an equestrian monument to his father for the Piazza della Signoria.

♦Equestrian monument to himself, Piazza Santissima Annunziata, Florence. Ferdinando commissioned Giambologna to cast an equestrian monument of himself for the Piazza della Annunziata.

|

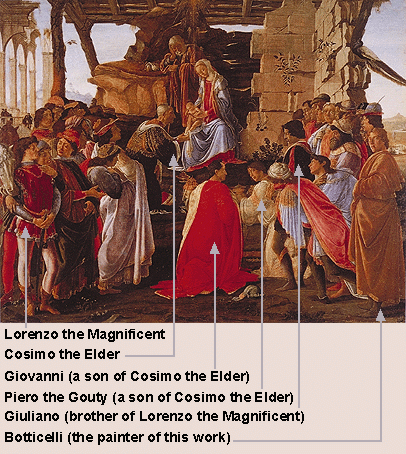

Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi, early 1470s. This painting includes figures that may represent members of the Medici family

See Also: ●Benozzo Gozzoli's Procession of the Magi ●Raphael's Portrait of Leo X with Cousins

|

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back