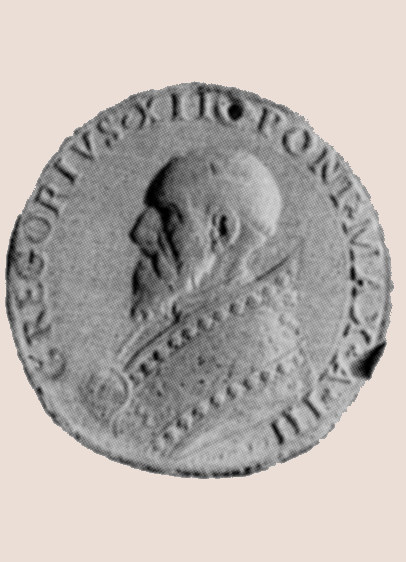

Gregory XIII

May 14, 1572 - April 10, 1585

BACKGROUND

Birth and Family

Pope Gregory XIII was born Ugo Boncompagni in 1502 in Bologna. His father was a merchant.

Education and Early Career

Ugo studied canon and civil law at Bologna University, where he took a doctorate and remained to teach for eight years (1531-39).

Among his students were several individuals who later became very important cardinals such as Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, the grandson of Pope Paul III, Cardinal Reginald Pole, a member of the House of York in England, and Cardinal Carlo Borromeo, Pope Pius IV's much-respected nephew who was made a Saint.

PRE-PAPAL CAREER IN ROME

Secretary to Cardinal Parisio

Thanks to his knowledge of canon law, Ugo was made a secretary to Cardinal Parisio in Rome.

Appointments Under Paul III

Pope Paul III appointed Ugo First Judge of the Capitol and papal abbreviator (drafter of papal bulls), among other titles. In 1547, he traveled to Bologna as one of Paul III's representatives at the early sessions of the Council of Trent.

While in Bologna attending sessions of the Council of Trent, Ugo fathered a child, Giacomo, with Maddalena Fulchini.

Appointments Under Julius III

During the pontificate of Pope Julius III, Ugo continued to rise in the hierarchy of the Curia and became a pontifical secretary in 1552.

Appointments Under Paul IV

Pope Paul IV appointed Ugo to accompany and advise his nephew Cardinal Carlo Caraffa on diplomatic missions to France in 1556 and to Brussels in 1557. In 1558, Paul IV appointed Ugo Bishop of Vieste.

Appointments Under Pius IV

Pope Pius IV sent Bishop Boncompagni to the Council of Trent as his confidential deputy from 1561 to 1563. This was the final phase of the Council, when the focus was on drafting recommendations for Church reform.

In 1565, Pius raised Ugo to the rank of cardinal priest.

Pius IV also appointed Cardinal Boncompagni his legate, or representative, to Philip II. Although from a papal point of view, Boncompagni's mission to Spain was not successful, the Spanish king came to respect Boncompagni and later favored his election as pope.

ELECTION AS POPE

Farnese as Leading Candidate

At the beginning of the 1572 conclave to choose Pius V's successor, the favorite was Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who had been an important force in the College of Cardinals since his election to the cardinalate by his uncle Paul III in 1534.

Selection of Cardinal Boncompagni

Although Farnese lacked the support to be elected pope, he had enough influence to affect the selection. His list of cardinals he would be willing to support included Cardinal Boncompagni, who had also been suggested by Cardinal Carlo Borromeo. (Cardinal Borromeo had already declined nomination.)

Reform-Oriented Selection

Because he had participated at the Council of Trent and helped draft its recommendations for reforming the Church, Cardinal Boncompagni was an apt choice for continuing to carry out Tridentine (based on the Council of Trent) reforms.

REFORMING THE CLERGY

Establishing Clerical-Abuse Committee

Soon after taking office, Pope Gregory XIII appointed a number of committees of cardinals to discover and eradicate any forms of abuse by the clergy that were not already being corrected.

Enforcing Clerical Residence

Like his predecessor Pius V, Gregory, was insistent that churchmen of all ranks reside in their ecclesiastic residences.

Gregory energetically used both diplomatic and military means in attempting to bring Protestant nations, particularly Poland, Sweden, and England, back to Catholicism. While one of Gregory XIII's envoys did succeed in convincing the Swedish king, John Wasa III, to secretly convert to Catholicism, his conversion was short-lived, and he soon returned to the Protestant fold. In the case of England, Gregory XIII favored an invasion, but he was unable to bring it about.

INSTITUTIONS FOR REFORM

Supporting and Founding Orders

Pope Gregory XIII recognized the potential of reform-oriented orders to spread the teachings of the Church and restore its image.

The pope strongly supported the recently founded Jesuit order, which had been approved by Paul III in 1540. Because the order's emphasis on spreading the faith coincided with the Pope's zeal for combating Protestantism in Europe and paganism in the New World and the East, he funded them to run colleges and conduct missionary activity around the world.

Gregory approved the foundation or expansion of several new orders including the Congregation of the Oratory (Oratorians) founded by Philip Neri (1575), the Barnabites (1579), and the Discalced (Shoeless) Carmalites, who were founded by Saint Teresa of Avila as an offshoot of the Carmalite order (1530, recognized 1575). The original Carmalite order had been founded in the thirteenth century by a community of hermits.

Establishing Colleges

Gregory XIII believed that persuasion through education could be a powerful tool in the battle against the defections of Catholics in Europe. To stop this movement and bring Protestants back to the Church, Gregory gave financial support to existing colleges and established many new ones.

These colleges were largely run by the Jesuit order and were intended to train future priests. Pope Gregory expanded the German College in Rome, which trained young Germans who aspired to be priests. They were trained in groups of over a hundred at a time and then sent back to their homelands to become agents of change.

Using Bartolomeo Ammannati as his architect, the pope also enlarged the Roman College, which had been established by the founder of the Jesuit order, Ignatius Loyola. This institution was later renamed the Gregorian University in Gregory's honor.

Among the colleges Gregory founded in Rome were the Greek college (1577), the English college (1579), the Maronite college (1584), the Armenian college, and the Hungarian college.

Sponsoring Missionary Activity

Because the Jesuit Order's emphasis on spreading their religion coincided with the pope's approach to combating Protestantism in Europe and paganism in the New World and the East, he funded them to conduct missionary work around the world.

Many of the colleges established by Gregory XIII were focused on training missionaries to convert residents of countries that were predominantly pagan. Gregory sent missionaries to China, Japan, and India in the Far East and to Brazil in the New World. The Jesuits established schools that taught Catholicism and played a major role in the world-wide diffusion of the Catholic faith.

Using Nunciaries for Persuasion

In recognizing the value of persuasion in achieving reform, Pope Gregory called for embassies, ambassadorial residences in foreign cities, to play a more active role in converting Protestant leaders and negotiating for the rights of Catholics to practice their religion. With these goals in mind, Pope Gregory established embassies in more foreign cities, particularly in what is now Germany.

EMENDING ECCLESIASTIC DOCUMENTS

Overview

Pope Gregory commissioned the scholarly revision of many Christian texts and directed committees to emend (correct) some of the Church's official documents.

Emendation of Corpus Juris Canonical

The Corpus juris canonical contained the official law code of the Roman Catholic Church, which consisted of a series of historical decrees.

The project to establish an official corrected version was called for at the Council of Trent and begun by Pius IV, who appointed a committee that included Pope Gregory when he was a bishop. Gregory continued his work on ecclesiastical law as a cardinal under Pius V, contributing to a critical edition of Gratian's Decretum.

As pope, he directed the committee to continue and approved its emendation in 1580. The new code was published in 1582.

Emendation of Roman Martyrology

In 1580, Pope Gregory commissioned a committee of ten specialists, led by Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto and including Cesare Baronius, to write a new Roman Martyrology. The new text was closely founded on earlier versions believed to be authoritative, including the Martyrology of Saint Ciriaco of Rome and the version compiled by the Benedictine Usard. (Usard was a ninth-century Benedictine monk and scholar who had been commissioned by Charles the Bald to produce an abridged compilation of earlier martyrologies.)

Because the first two editions (1583) were full of errors, they were suppressed after the publication of a corrected edition in 1584.

ENCOURAGING PILGRIMAGES TO ROME

Declaring 1575 a Jubilee Year

Pope Gregory XIII inspired the faithful to undertake pilgrimages to Rome by declaring 1575 a Jubilee Year. Around 400,000 visitors came to Rome that year. Confraternities provided food and shelter.

Income for the Church

While in Rome, pilgrims visited the city's historic churches, especially the major pilgrimage churches and prayed to saints, who were often represented by relics and images. The influx of visitors brought money to the church and the city.

Preparations in City of Rome

In preparation for the mass arrival of foreign visitors, Pope Gregory enacted a program of urban renewal. He repaired the Vergine aqueduct and added fountains to several piazzas.

In addition to improving some of Rome's major streets, Gregory continued construction of the Via Angelina and built the Via Merulana, which connected the pilgrimage churches of Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano.

Papal Promotion of Pilgrimages

Pope Gregory promoted touring holy sites by making public visits to important sites himself. At the age of seventy-three, Pope Gregory climbed to the top of the Scala Santa at Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano on his knees. The Scala Santa, meaning the "Holy Stairs," is believed to have been brought from Pontius Pilate's palace in Jerusalem.

INSTITUTING THE GREGORIAN CALENDAR

The Julian Calendar's Inaccuracy

Because the system of keeping track of time that had been instituted under Julius Caesar (c.100 -55 BC) contained a small inaccuracy, the solar-based calendar was no longer synchronized with the occurrences of the equinoxes.

(The vernal equinox marks the beginning of spring, around March 21, and the autumnal equinox marks the beginning of fall, around September 22. The equinoxes occur when the sun crosses the imaginary plane defined by the equator, marking the transitions from the northern to the southern hemisphere in the spring and from the southern to the northern hemisphere in the fall.)

The motivation for reforming the calendar stemmed primarily from wanting to celebrate sacred events at the correct times, and the date of Easter celebrations is determined by the spring equinox. Consequently, the inaccuracy in the Julian calendar caused the civil and solar calendars to fall ever further out of synch, leading to an increasingly early date for Easter celebrations. Gregory's aim was to harmonize the two and restore the traditional Easter period.

Correcting the Calendar

The new "Gregorian Calendar" reset the date from October 5 to October 14 and adopted a calendar of 365 days. An extra day was added at the end of February every fourth year, and the years with 366 days are called "leap" years.

Dates of Adoption

The new calendar, which is still in use, was adopted in 1578 in Catholic countries. Protestant countries, who suspected Catholic motives, were slow to adopt it. In England, for instance, it was not adopted until 1752.

Prestige from New Calendar

Adopting a calendar that was scientifically more accurate reflected well on the church and its claims to universality. Furthermore, the calendar was now named for a Catholic pope instead of a pagan Roman Consul.

The construction of the Tower of the Winds, a four-story tower at the Vatican, celebrated the achievement.

PROPERTY CONFISCATION AND CRIME

Church Debt

Gregory XIII spent liberally on infrastructure, education, and expansion of the church. He established new colleges and foreign missions and embarked on an extensive building program involving new roads, new buildings, and many restorations. His spending exceeded the revenue coming into the church by a considerable amount, creating much debt.

Confiscation of Nobles' Property

To raise additional funds, Gregory resorted to confiscating the property of nobles in the Papal States on the basis of irregularities in old legal records concerning titles and debts.

Crime and Lack of Order

After being dispossessed of their wealth and land, some impoverished nobles turned to supporting banditry and other unlawful activities, creating a state of lawlessness and near anarchy in the Papal States.

The local police cooperated with gangs led by nobles, and by 1583, riots were breaking out in Rome. Order was not restored in the region until the pontificate of Gregory's successor, Sixtus V.

ASSESSMENT

Positive Accomplishments

Pope Gregory was effective as a pope in a period in which the Church needed to redefine itself. He matched his predecessor Pius V in his zeal for carrying out Tridentine Reforms, but he differed from him in approach. Gregory XIII placed less emphasis on prosecuting heretics through the Inquisition, and instead, he established colleges to train new clergy, an innovation as there had not been a specific, standardized training program before this time.

The pope also made effective use of religious institutions like reform-oriented orders that were active in spreading Catholicism around the world.

He commissioned corrections of important church documents and instituted a more accurate calendar that is in use today and bears his name.

His measures were effective, and the Church was successful in improving its image and regaining some parts of Germany that had become Protestant.

Failure to Maintain Civil Order

Seizing the property of noble families was a poor solution to the budget shortfall and contributed to banditry and a general state of lawlessness.

Nepotism on a Small Scale

Although Pope Gregory did promote a few of his relatives, his awards to them were nominal compared to the excesses of the Borgia, della Rovere, and Medici popes, who loaded their relatives with benefices and, at times, conducted foreign policy in accordance with their family's interests.

He awarded cardinalates to two nephews whom he considered worthy of high office but withheld such an office from a third, less-worthy nephew.

Gregory appointed his illegitimate son, Giacomo, governor of Castel Sant' Angelo and arranged for him to marry a member of the Sforza family. He also furthered Giacomo's career by arranging favors from beyond the Papal States. The Venetian state added Giacomo to their directory of nobles, and Philip II made him a general in the Spanish army.

Celebrating a Massacre

One of the most questionable episodes of Gregory XIII's pontificate was his celebrating news of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in which thousands of French Huguenots (French Protestants) were slaughtered on the eve and day of St. Bartholomew (August 23 and 24, 1572).

Gregory declared a general jubilee and had the Te Deum sung in the church of San Marco to give thanks for the liberation of France. He recorded the massacre visually in both a medal and three scenes of Vasari's frescoes in the Sala Regia at the Vatican Palace.

Gregory's reaction has been defended on the basis that he had been informed that the slaughtered Huguenots had plotted to overthrow the French government and kill the ruling family. Considering the secrecy that such a plot would have required, it is unimaginable that so many men, women, and children could possibly have been complicitous.

It is generally recognized that the primary motivation for the massacre was political enmity rather than religious fervor or revenge against the participants of a treasonous plot.

Plotting Elizabeth I's Overthrow

Pope Gregory's approach to England was particularly aggressive, and he supported two attempts to launch attacks from Ireland to overthrow England's Protestant queen, Elizabeth I. He felt justified in this aggression because she was persecuting Catholics in response to the many Catholic-sponsored plots against her.

PATRONAGE

Projects Outside Rome

As head of the Papal States, Pope Gregory commissioned civic and ecclesiastic projects in many places.

♦Ports. The pope, who understood the importance of ports to the economy of the Papal States, built new ports at Cesenatico and Ravenna and strengthened the fortifications at Civitavecchia.

♦Street and sculpture in Loreto. Gregory XIII made several improvements at Loreto, which was a magnet for pilgrims because of the presence of Santa Casa (Holy House), the supposed house of the Virgin Mary. He built a road and named it the Via Boncompagni for his family. He also commissioned further decoration to the marble shell designed by Bramante to enclose the holy structure.

Civic Commissions in Rome

To beautify Rome for the 1575 Jubilee, Pope Gregory undertook many projects early in his pontificate. He eased the way for urban renewal projects such as widening streets and building new roads by passing legislation in 1574 to allow land to be seized in the interest of public projects. The new law also required buildings to be built next to each other, which eliminated the narrow passages between buildings that became filled with garbage.

♦Continued construction of Via Pia. Pope Gregory continued the construction of the Via Angelina, which had been begun by Pius IV.

♦Initiated construction of the Via Merulana. The pope built the Via Merulana, which connected Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano two of Rome's 's major pilgrimage churches.

♦Improved Piazza Navona by repairing aqueduct nearby and adding fountains to ends. The pope commissioned the repair of the city's major aqueduct, the Acqua Vergine. Part of its water flowed into the fountains at the Piazza Navona. Gregory XIII commissioned Giacomo della Porta to install fountains at each end. At the center of the piazza was a long low fountain intended as a trough for horses. Only the fountain at the southern end was completed with figures, and it was redesigned in the seventeenth century by Bernini, who repositioned its tritons (mermen) around a statue known as the Moor, which has vaguely African features and holds a dolphin. Bernini made the piazza's central fountain, the Fountain of the Four Rivers, in the 1650s. Figures were not added to the northern fountain until the nineteenth century, when a Neptune group was installed.

♦Added Fountain to Piazza della Rotunda. Pope Gregory commissioned Giacomo della Porta to design a fountain for the Piazza della Rotunda, which stands in front of the Pantheon.

♦Converted part of the Baths of Diocletian to Grain Storage. To build a grain-storage facility, the pope utilized part of the old construction of the ancient Baths of Diocletian, which had largely been converted to a Carthusian monastery.

♦Continued Construction of Palazzo Senatorio, Campidoglio. Pope Gregory continued the reconstruction of the façade of the Palazzo Senatorio, which Michelangelo designed as part of his plan for the Campidoglio.

Ecclesiastic Commissions in Rome

♦Churches. Pope Gregory refurbished venerated churches like Santa Maria Maggiore, whose porch needed restoration, and contributed to the building of new churches like Il Gesù, whose primary patron was Alessandro Farnese.

♦Colleges. Pope Gregory sponsored the expansion of the German and Roman Colleges and the building of new colleges for the Greeks, English, Maronites, Armenians, Hungarians, and others.

♦Residence on the Quirinal. Because of an outbreak of malaria at the Vatican in 1574, Pope Gregory decided to build a pontifical residence on the Quirinal, Rome's highest hill. He commissioned the work from Ottaviano Mascherino, and the project was begun in 1583. Gregory's successors expanded the project, which was not finished until the 1730s. The completed structure combines the size and formality of a royal palace with the expansiveness and landscaping of a villa. Today, the palace serves as the official residence of the President of Italy.

Commissions at the Vatican

♦Hall of Maps. On the west wing of the Belvedere Court, Pope Gregory added a fourth story, which contains a gallery called the Galleria della Carte Geografiche (the Hall of Maps), after the sixteen large maps of Italy that decorate its walls. Gregory commissioned Ignazio Danti to design its decoration.

♦Tower of the Winds. To celebrate his instituting the Gregorian Calendar, Gregory commissioned a four-story tower called the Tower of the Winds.

♦Sala Regia paintings. The pope commissioned Vasari to complete the scene of the Battle of Lepanto that he began for Pius V in the Sala Regia and to add three scenes illustrating the recent massacre of the Huguenots in France on St. Bartholomew's Day.

♦Drum of St. Peter's. Pope Gregory maintained Vignola as chief architect at St. Peter's. After Vignola's death in 1573, Gregory appointed Giacomo della Porta. In the opening years of Gregory's pontificate the drum was completed, but the dome remained for his successor.

♦Gregorian Chapel, St. Peter's. Gregory's most significant and influential project in St. Peter's was the construction of a chapel dedicated to St. Gregory of Nazianzus, now known as the Gregorian Chapel after its builder and its dedication. The chapel, which was located under the north subsidiary dome, was designed by Giacomo della Porta, and its decoration overseen by Girolama Muziano. The chapel is notable for the extraordinary richness of its decoration, made up of marbles, precious stones, mosaics, and bronze. It houses both the relics of St. Gregory of Nazianzus and the tomb of Pope Gregory XIII.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back