Sixtus V

April 24, 1585 - August 27, 1590

BACKGROUND

Birth and Family

Pope Sixtus V was born Felice Peretti in 1521 in Grottammare, which is near Ancona, a port city across the Adriatic Sea from Dalmatia. His father's family fled from Dalmatia in the fifteenth century, after the Turks began to flow into the region following the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Felice's family was poor and worked on a farm. Later, as Pope Sixtus V, he recounted how as a boy he tended pigs and his father worked in the fields.

Education

Peretti's uncle, a Franciscan friar, sent him to be educated at the Franciscan monastery at nearby Montalto. Felice joined the monastery as a novice when he was twelve. He attended the universities in Ferrara, Bologna, and Fermo and completed a doctorate in 1548, a year after having been ordained a priest in Siena.

Early Career

Peretti, who was a gifted administrator, served as the rector of the Franciscan monasteries in Siena (1551), Naples (1553), and Venice (1556).

PRE-PAPAL CAREER IN ROME

Association with Important Cardinals

Because Peretti had developed a reputation as an orator, Cardinal Carpi, who was the protector of the Franciscan order, took him to Rome in 1552 to deliver the Lenten sermons. His fiery sermons brought him to the attention of Cardinals Caraffa and Ghislieri, with whom he shared many attitudes and beliefs. After they became Pope Paul IV and Pope Pius V, respectively, they employed him in increasingly important positions.

Career Under Paul IV

When Paul IV's pontificate began, Peretti was serving as a rector in Naples.

=Member of Reform Committee. Paul IV appointed Peretti to serve on his reform committee.

=Head of Inquisition in Venice. In 1556, Paul IV appointed Peretti to head the Inquisition in Venice, a position that Paul IV had also held early in his career. Peretti's harshness led the Venetian government to ask for him to be recalled, which took place under Pope Pius IV in 1560.

Career Under Pius IV

In 1565, Pius IV assigned Peretti to accompany Cardinal Ugo Boncompagni's delegation to Spain to investigate heresy charges against the Archbishop of Toledo. At this time, he and Cardinal Boncompagni, the future Pope Gregory XIII, developed a dislike of each other.

Career Under Pius V

Pius V noted that Peretti's past was similar to his own. Both of them had been poor, worked as herders, and been educated at monasteries, where they had been able to distinguish themselves as scholars.

=Bishop of Saint Agatha of the Goths. In 1556 Pius V named Peretti the Bishop of Saint Agatha of the Goths in Naples.

=Confessor to the Pope. Peretti became Pope Pius' confessor, a privileged position of confidence.

=Vicar General of the Franciscan Order. In 1566, Pius V appointed Peretti to be the Vicar General of the Franciscan Order.

=Cardinal di Montalto. In 1570, Pope Pius made Peretti a cardinal with the titular church of Saint Simeone. Peretti was generally called Cardinal di Montalto in reference to the Franciscan monastery where he had begun his ecclesiastic life.

Career Under Gregory XIII

When his old enemy Cardinal Boncompagni became Pope Gregory XIII, Cardinal di Montalto withdrew from public life. He concentrated on producing a scholarly edition of the writings of Saint Ambrose, one of the four original "doctors" of the Church. He also built a villa designed by Domenico Fontana on the Esquiline, one of Rome's seven hills.

Election as Pope

During the thirteen-year period of Gregory XIII's pontificate, Cardinal di Montalto's absence from public life served to shield him from conflicts within the Curia. With his dark-horse status and the support of powerful friends such as Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici, who became Duke of Tuscany upon the death of his older brother in 1587, Cardinal di Montalto was elected on the fourth day of the conclave that opened after Gregory XIII's death in 1585.

ESTABLISHING LAW AND ORDER

Taking Drastic Action Against Criminals

As pope, Sixtus V took stern measures to end the banditry and general lawlessness that had developed under his predecessor, who had driven many nobles to crime by seizing their property. He ordered that anyone caught stealing or carrying a weapon would be hung.

Hanging Criminals and Displaying Heads

Criminals were hung publicly from gallows erected around the city, and in at least one well-known case, the head of an executed offender was displayed on the bridge in front of the Castel Sant'Angelo.

Punishing Other Crimes More Harshly

Prostitutes were not allowed to leave a small district of Rome.

The death penalty was applied to pimps and mothers who put their daughters into prostitution.

Creating Police-State Environment

The police had the right to enter the homes of citizens on mere suspicion, and Romans lived in terror.

Establishing Order in Two Years

Although the number of criminals has been estimated to have been many thousands, Pope Sixtus V's strong measures solved the crime problem within a couple years.

REORGANIZING THE CURIA

Thorough Restructuring

Pope Sixtus V is particularly noted in papal history for his complete reorganization of the Curia, the papal administration. His reworking of the system made it more efficient and provided for a more even distribution of the work.

Longevity of His System

Sixtus' restructuring was so effective that it remained unchanged until the early 1960s, when changes were made by the Second Vatican Council.

Fifteen Permanent Departments

The work of the Church was divided into fifteen categories, For each category Sixtus appointed a permanent congregation of cardinals to administer it. Among the fifteen congregations were the Inquisition, the Index of Forbidden Books, the Council of Trent, Rites and Ceremonies, Pubic Welfare, Establishment of Churches, and Roads, Bridges, and Waters.

Strengthening of Pope's Power

Sixtus V's changes to the Curia centralized and strengthened the pope's authority and changed the nature of his dealings with the cardinals. Arranged into congregations, the cardinals reported to the pope, who made the final decisions. With this structure in place, the cardinals were clearly shown to be subordinate to the pope, rather than ruling with him, thus weakening their power.

RELATED CHANGES

Limiting the Number of Cardinals

Pope Sixtus fixed the number of cardinals at seventy. This number stayed in force until John XXIII (1948-63) raised it.

Sixtus defined more stringent guidelines for the selection of cardinals. Having children or grandchildren disqualified potential candidates.

Bishops to Report on Dioceses

Sixtus revived a law that required bishops to report on the state of their dioceses every five years.

FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

From Debt to Surplus

Sixtus V's financial management turned the deficits he inherited from his predecessor's pontificate to surpluses despite the fact that he spent enormous sums remaking Rome into a Christian capital. The surplus, stored in Castel Sant'Angelo, was so great that the pope was one of the richest leaders in Europe.

Although the buildup and retention of capital initially worked to the Papal State's economic advantage, keeping such a significant amount of money out of circulation soon began to damage the economy.

Means of Raising Revenues

In addition to cutting expenditures on everything except architecture, Sixtus instituted several policies to raise money.

=Taxing food. Sixtus imposed a tax on all food, which made him immensely unpopular.

=Selling church offices. Sixtus V revived the practice of selling offices. Julius II's ban on this practice had been enforced since the time of Paul IV.

=Extending loans. The pope financed public loans at interest.

PROMOTING FRANCISCAN ORDER

Franciscan Background

Pope Sixtus V was a strong advocate of his own order, the Franciscans, who had educated him and employed him as a preacher, as the rector of three different monasteries, and as the vicar general of the Order.

Selecting the Name "Sixtus"

Sixtus V chose the papal name "Sixtus" in homage to Sixtus IV, the last Franciscan pope.

Giving Generous Financial Support

Sixtus V was generous in his endowment of the Franciscan order and its facilities.

Promoting Status of Prominent Franciscans

Pope Sixtus raised the status of several prominent Franciscans.

●Declaring Saint Bonaventure a Doctor. Pope Sixtus declared the thirteenth-century Franciscan theologian Saint Bonaventure a doctor of the Church. (The four Latin Doctors of the Church are St. Gregory the Great, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and St. Jerome.)

●Canonizing Diego of Alcalà. At the request of Philip II, in 1588 Sixtus canonized the Spanish hermit priest Diego of Alcalà, who was a Franciscan.

Building the Cappella Sistina

At Santa Maria Maggiore, Sixtus commissioned the Cappella Sistina, which is also known as the Chapel of the Presepio (Manger). As a Franciscan, Sixtus V was particularly devoted to the Incarnation of Christ and often had himself depicted with imagery related to the birth of Christ.

The manger in the Cappella Sistina dates back to the seventh century and was revered and updated throughout the centuries, including with a statue group by Arnolfo di Cambio in the thirteenth century. The manger and statues are preserved under the high altar in the center of the Cappella Sistina.

VATICAN PRESS AND PUBLICATIONS

Establishing Vatican Press

In 1587, Sixtus V established the Vatican press.

Edition of Septuagint

One of the first publications of the newly established Vatican Press in 1587 was a new edition of the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament.

Sistine Vulgate

In fulfillment of the Council of Trent's call for a new edition of the Vulgate, St. Jerome's Latin translation of the Old Testament, Sixtus V set up a commission to produce a new one.

Sixtus V, who was a scholar himself, became impatient and took on the project himself. In haste, he brought out the Sistine Vulgate in 1590. It was so full of errors that it was withdrawn after his death that same year.

The Sistine Vulgate was replaced in 1592 by the Clementine Vulgate, which was published by his successor, Pope Clement VIII. The Clementine Vulgate remained the official version until the 1960s.

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Opposition to Huguenots

In France, Sixtus V opposed the Huguenots (French Protestants) by supporting the Catholic League, a French organization aimed at maintaining Catholic power. He was guarded in his support for his Catholic ally, King Philip II of Spain, because he feared that increasing the king's power would give the Spanish greater hegemony in Italy.

Sixtus issued a bull against Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot who was one of the three Henrys fighting for the throne of France. The bull stated that Henry of Navarre was a heretic, that he had lost any right to succeed to the throne of France, and that his subjects were not obligated to obey him.

The War of the Three Henrys ended with the accession in 1590 of Henry of Navarre after the assassinations in 1588 and 1589, respectively, of Henry of Guise, a nobleman who headed the Catholic League, and of King Henry III, the third son of Catherine de' Medici.

Henry of Navarre was unable to take control of Paris until after he converted to Catholicism in 1593, three years after Sixtus V's sudden death from malaria.

Not Paying Share for Armada

Sixtus V encouraged Philip II of Spain to invade England, ruled by the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I. Sixtus promised to pay a million scudi toward the expense of raising the Spanish Armada, a fleet of 130 ships carrying thirty-thousand men, but after the Armada's defeat in 1588, he refused to pay.

ASSESSMENT

Summary of Major Accomplishments

Sixtus V accomplished a phenomenal amount in his five years as Pope.

●Re-establishing law and order. Enacting a harsh code of justice enabled Sixtus to restore law and order to Rome within two years of taking office.

●Reorganizing the Curia. Sixtus restructured the papal administration into fifteen Congregations (committees) of cardinals. The new system worked so well that it was used for over three and a half centuries.

●Establishing Vatican Press. Sixtus established a press at the Vatican and published new editions of several important documents.

●Continuing Church reform. Sixtus continued to carry out reforms at home and to spread Catholicism abroad through missionary activity in Japan, China, the Philippines, and South America.

●Re-establishing Catholicism in some areas. Sixtus minimized Italian participation in the ongoing wars in Europe and succeeded in bringing some parts of Europe back to Catholicism.

●Turning debt to surplus. Sixtus turned debt to surplus by cutting expenses and increasing Church income. To achieve the latter, he taxed food, sold Church offices, and extended loans.

●Bringing fresh water to Rome. By rebuilding 22 miles of a Roman aqueduct, Sixtus brought fresh water to Rome from Palestrina.

●Increasing the food supply. Sixtus V, who experienced poverty as both a child and a member of a mendicant order, wanted to improve the lives of the populace by improving economic conditions and public facilities. He increased the amount of land available for farming by draining marshes. He regulated food prices to avoid drastic price swings.

●Transforming city to Christian capital. By refurbishing buildings, repaving streets, adding new streets, enlarging church piazzas, and erecting obelisks, Sixtus transformed Rome into a grand capital of Christendom.

Unpopularity

Like Paul IV and Pius V, who had both befriended him when they were cardinals and appointed him to positions of responsibility when they were Popes, Sixtus V was unpopular because of his harshness as head of the Inquisition and the police force and because he expanded their jurisdiction to include public morality.

Sixtus' tax on food also earned him much hatred. As had been the case with Paul IV, after Sixtus V' death angry mobs demonstrated their rage by tearing down a statue of him that had been erected on the Capitoline hill.

CITY PLANNING IN ROME

Broad Approach

Sixtus V revolutionized the appearance of the city of Rome through a combination of refurbishing and improving its infrastructure, building new streets to connect major pilgrimage churches, enlarging and remodeling piazzas, and using colossal ancient columns and obelisks to create monumental landmarks. The law passed under Gregory XIII providing the civil government the right to take property for public use was key to Sixtus' ability to enlarge piazzas and build long, straight roads.

Destruction of Ancient Buildings

Unfortunately, some of the clearing affected ancient Roman architecture, which Sixtus did not value because of its pagan roots. He ordered the destruction of the palace of Septimius Severus and part of the Baths of Diocletian, of which much had already been converted to a Carthusian monastery and church under Pope Pius IV.

Adding and Improving Streets

Streets were important because they helped pilgrims find their way from site to site and facilitated penitential processions, a medieval practice that Sixtus V revived.

Sixtus re-paved 121 of the existing streets of Rome, widening many of them.

Sixtus V changed the urban flow of Rome decisively by building five new streets that linked pilgrimage churches and made Santa Maria Maggiore a central hub.

♦Strada Felice. The Strada Felice (now Via Sistina) connects Santa Maria Maggiore with the church of Trinità del Monti.

♦Via Santa Croce. The Via Santa Croce connects Santa Maria Maggiore with the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, which is outside the city walls.

♦Via San Lorenzo. The Via San Lorenzo connects Santa Maria Maggiore with the church of San Lorenzo Outside the Walls, which, as the name suggests, was outside the city walls.

♦Via Panisperna. The Via Panisperna connects Santa Maria Maggiore with the area approaching the hill of the Campidoglio.

♦Via San Giovanni. The Via San Giovanni connects San Giovanni in Laterano with the ancient Roman Colosseum.

Building and Enlarging Church Piazzas

Pope Sixtus V embarked on an ambitious program of accentuating the city's most important pilgrimage churches by enlarging and improving the piazzas associated with them. He employed the architect Domenico Fontana to design and carry out his urban projects.

Restoring Aqueduct and Building Fountains

Sixtus' increased the water supply to Rome by restoring an ancient aqueduct. This not only provided the inhabitants with a source of water but also made it possible to supply water for the many fountains that Sixtus subsequently built.

♦Acqua Felice, Rome to Palestrina. Sixtus V began restoration of a 22-mile long section of the ancient Roman aqueduct in 1585 and opened it in 1589. The aqueduct flowed into the Moses Fountain (also known as the Fontana dell'Acqua Felice), a large fountain on the Quirinal, Rome's highest hill. The restored aqueduct brought fresh water to the entire city for the first time since the days of the Roman empire. Until that point, Romans were dependent on the polluted waters of the Tiber River.

♦Fontana dell'Acqua Felice, Piazza San Bernardo. The Fontana dell'Acqua Felice was built by Domenico Fontana. It is also called the Moses Fountain for the sculpted figure of Moses striking a spring in the rock. The iconography of the fountain was Sixtus' answer to the pagan Neptunes commonly placed on fountains. With the arrival of a source of fresh water to the Quirinal, it became possible to occupy the site, and many villas were subsequently constructed on the hill, particularly by cardinals. Sixtus V's patronage is announced by the many symbols from the Peretti coat of arms.

REUSING ANCIENT MONUMENTS

Using Ancient Monuments in Piazzas

Although Sixtus had little interest in pre-Christian architecture, he did have the imagination to realize that the colossal ancient monuments that were around the city of Rome would add grandeur and unity to piazzas and serve as highly visible landmarks to help pilgrims, for whom Rome was unfamiliar territory, locate important pilgrimage churches.

To this end, he utilized colossal sculptures, which the Romans brought back from Egypt as trophies of their conquests. Most impressive were monumental columns, which the Romans made to celebrate the achievements of their emperors, and obelisks, which were entrances of Egyptian temples.

Christianizing Ancient Monuments

To remove the taint of paganism, the monuments were Christianized in ceremonies conducted by Sixtus. Their conversions were proclaimed by inscriptions on pedestal bases and crosses or statues of saints on top.

Moving and Erecting Obelisks

Unlike the monumental columns, which were still standing, all except one of the obelisks had fallen, and some had to be searched for and excavated from under the debris that accrued over time. All were moved to the piazzas of important churches by Domenico Fontana.

The obelisk that remained standing was the one beside St. Peter's, which had overlooked the site of the martyrdoms of many Christians, including, perhaps, the crucifixion of St. Peter himself.

Four obelisks were erected at new sites, and if Sixtus' pontificate lasted longer, three others would have been erected at other sites: St. Paul's Outside the Walls, Santa Maria degli Angeli, and Piazza Navona. The fragment of an obelisk that now rises at the center of Piazza Navona as the crowning element of Bernini's Four River's Fountain was added in the seventeenth century.

Examples in Rome

Pope Sixtus initiated making ancient works such as colossal sculptures, monumental columns, and obelisks the centerpieces of important piazzas.

♦Horse Tamers Sculptural Group, Quirinal. At the Quirinal Palace, Domenico Fontana erected a sculptural group for Sixtus V in 1589 using a pair of statues representing the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, who are often referred to as the "Horse Tamers." The statues were moved from the entrance of the Baths of Constantine and positioned side by side in front of the Quirinal Palace. In 1786 an obelisk was added, and they were re-positioned. The giant basin was not added until 1818.

♦Column of Trajan, Piazza Venezia. The Column of Trajan, originally the centerpiece of the Forum of Trajan, is now surrounded by Piazza Venezia near the Vittorio Emanuele Monument and the Palazzo Venezia. Sixtus had a statue of St. Peter placed on top, and in 1587 he dedicated the column as a Christian monument.

♦Column of Marcus Aurelius, Piazza Colonna. The Column of Marcus Aurelius, which originally stood in front of the Temple of Marcus Aurelius, is now the center of the Piazza Colonna. The column was crowned by a statue of the apostle St. Paul and dedicated in 1588.

♦Obelisk, Piazza di San Pietro, Vatican. The obelisk in front of St. Peter's was brought from Egypt by Caligula in A.D. 38 and erected in the center of the hippodrome known as Nero's circus. After the complex of buildings making up the Vatican was built on and beside the site of Nero's hippodrome, Old St. Peter's was located beside this obelisk, which was left standing because it was regarded as the last witness of many martyrdoms. It is the second tallest of Rome's obelisks (the tallest is that at San Giovanni Laterano). Sixtus commissioned Domenico to position the obelisk in front of St. Peter's at a point that was then outside the entrance to the Vatican. Domenico Fontana became famous in his own lifetime as the architect-engineer who succeeded in moving this obelisk into a new position. There is a story that when the obelisk was being erected, the pope ordered everyone to be silent under pain of death. When the strain seemed to be near breaking the overheated ropes, a sailor saved the day by yelling out "Water on the ropes." Instead of death, he was honored as his town, Bordighera, received a concession to supply palms for Palm Sunday. Sixtus identified himself with the obelisk by including symbols from his family's arms at its base and top.

♦Obelisk, Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano. The Lateran obelisk, the largest standing obelisk in the world, was brought to Rome from the Temple of Amen in Thebes in A.D. 357. The obelisk was particularly important to the papacy as it had been brought to Rome on the order of the first Christian emperor, Constantine, whose connection is emphasized in the dedication and inscription on the base. Constantine died in 337, before the obelisk had been brought to Rome, and it was his son Constantius who carried out its shipping and installation in the Circus Maximus, Rome's largest hippodrome. Before Domenico moved this obelisk in 1587-88, it lay in three pieces under a layer of dirt and debris from the ruined hippodrome. It was positioned in the Piazza San Giovanni Laterano so that it could be seen from several streets that entered the piazza, thus aiding pilgrims seeking San Giovanni in Laterano and the Holy Stairs.

♦Obelisk in Piazza dell' Esquilino. The red granite obelisk in the Piazza dell' Esquilino, which stands at the rear of Santa Maria Maggiore, was brought to Rome by the Emperor Augustus. It was found at the remains of the Mausoleum of Augustus in 1519.

♦Obelisk in Piazza del Popolo. The obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo, which was the first to be brought to Rome from Egypt, was brought from Heliopolis in 10 BC by Augustus. It had been made for Rameses II.

ECCLESIASTIC PATRONAGE

Church Properties in Rome

Sixtus V rebuilt and repaired numerous churches, monasteries, and hospitals. He gave titular status to Santa Maria del Popolo and Santa Maria della Pace, which had been built by the last Franciscan pope to precede him, Sixtus IV. In addition to changes at the Vatican, he improved the papal residences at the Lateran and the Quirinal.

♦Santa Maria Maggiore and Piazza dell' Esquilino. Pope Sixtus restored the Early Christian church of Santa Maria Maggiore and made it the hub of several streets that led to other pilgrimage churches. Sixtus built a piazza on the church's rear that led to the Strada Felice (now the Via Sistina) and embellished it with an obelisk brought from the Mausoleum of Augustus. In the right transept, Sixtus added the richly decorated Cappella Sistina, which contained tombs for Pius V and himself. A crypt under a tabernacle in the chapel holds a nativity scene believed to incorporate stones from the grotto of Bethlehem and hay from Christ's manger. The nativity scene was housed in its own chapel, known as the Presepio and dated to the seventh century. It was the first structure built in imitation of the location where Christ was born. The relics and chapel were especially important to Franciscans, who are particularly devoted to the Incarnation of Christ.

♦San Giovanni and Lateran Palace. Sixtus made extensive changes at the complex of buildings at San Giovanni in Laterano. He demolished the old palace, which had been the principal residence of the pope before the papacy moved to Avignon, and replaced it with a new Lateran Palace designed by Domenico Fontana. Sixtus also added a Benediction Loggia to the right transept of San Giovanni. Further, he built a separate structure for the Holy Stairs, which had been housed in the old palace. He moved a reliquary there as well. The addition of an obelisk to the open area helped to unite the separate structures.

♦Quirinal Palace. Sixtus continued the Quirinal Palace, the papal summer residence began by Gregory XIII, who had selected the highest hill in Rome in hopes of finding better air during a malaria outbreak. Domenico designed the main façade and a fountain featuring a pair of ancient statues representing the horse tamers Castor and Pollux. The piazza was named Monte Cavallo (Mount Horse) for them. Sixtus' successors continued to expand the palace, which was finished in the 1730s. Today it serves as the official residence of the President of Italy.

Vatican Projects

At the Vatican, Sixtus worked on completing St. Peter's and building a new library.

♦Dome of St. Peter's. Under the architect Giacomo della Porta, Sixtus V had the dome of St. Peter's completed in 22 months by using a large force of 800 men working around the clock. Although it was different in detail and somewhat taller, which made it more stable, its engineering followed Michelangelo's double-shell design.

♦Vatican Library. Sixtus V commissioned Domenico Fontana to design a new home for the Vatican library to replace a smaller library founded by Pope Sixtus IV and located on the ground story of the Nicholas V wing. The design of the new second story, in which books were stored on shelves located along the outer walls, followed a design that had been introduced recently at El Escorial. The Library was lavishly decorated by Cesare Nebbia and others with scenes of famous ancient libraries as well as of Sixtus' buildings in Rome. The placement of the library across the recently completed Belvedere Court spoiled Bramante's thousand-foot vista. According to art historian James Ackermann, Sixtus' goal in building the library in that location was to destroy the Vatican's resemblance to a pleasure palace composed of fountain-filled gardens and a large theater. Sixtus closed the sculpture court to visitors because it contained nude statues like the Apollo Belvedere, and the Laocoön, whose propriety at the Vatican had also been questioned by Hadrian VI and Paul IV, who gave away many ancient works.

♦Palace of Sixtus V. Sixtus V commissioned Domenico Fontana to build a new palace, the Palace of Sixtus V, across the courtyard from Bramante's entrance façade. The palace, now the Apostolic Palace, forms a third wing of the Courtyard of S. Damaso and is a residence of the pope.

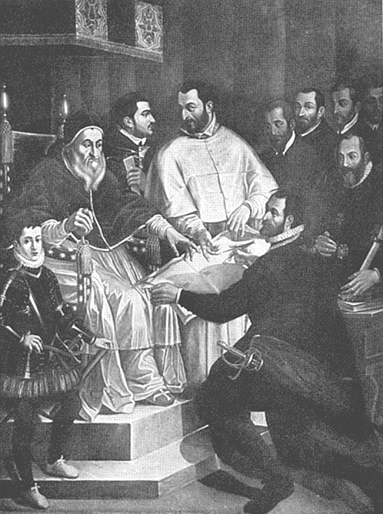

Pope Sixtus V Approving the Plan for the Reconstruction of the Vatican Library |

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back