Fortifications

INTRODUCTION

Seminal Period in Fortification Design

Because the introduction of gunpowder into Europe at the dawn of the Renaissance created a need for artillery-resistant fortifications, the field of military architecture offered an opportunity for architects to use their creative gifts to develop a new system.

The revolutionary new approach to the design of fortifications that developed in Italy has been called the most original architectural innovation of the Renaissance.

Later Standardization

Once a best solution was reached, fortification designs became formulaic, and the field became a specialty of military engineers. Because fortifications ceased to vary much at that point, the most vital and interesting period of Italian fortification design was during the transitional period when architects were experimenting with new solutions.

GUNPOWDER

Definition and Properties

Gunpowder is an explosive mixture of potassium nitrate (40 - 75%) with charcoal and sulfur. Among explosives, gunpowder is one of the less powerful types because of its relatively slow rate of combustion, which makes it suitable as a propellant in guns.

In cannon, the gunpowder is packed into a small chamber located behind the barrel, and after ignition, it quickly releases gas that pushes the missile packed next to it through the barrel. Explosives with a fast rate of combustion would destroy the gun barrel because of the rapidity of the release of gas.

Less than half of the substance is converted to gas, and the rest becomes soot and smoke.

History

Although the invention of gunpowder is widely attributed to the Chinese in the first millennium, the evidence of its origin is inconclusive. The Arabs, who are credited with gunpowder's refinement, may have played a larger role in its invention, and simultaneous development in several places is also possible.

Gunpowder's properties and ingredients were first recorded in Europe around 1268 by Roger Bacon, an English monk who practiced alchemy, an early form of chemistry that attempted to produce gold from less valuable metals.

Early Use in Weapons

The Chinese were the first to utilize gunpowder as a weapon by packing it into a bomb delivered by a catapult. Later, they used gunpowder as a propellant in tubes made of bamboo.

These were succeeded by barrels made of metal in the twelfth century. Much of the subsequent development of gunpowder and guns took place in Europe.

Use in Weapons in Italy

In Italy, an early reference to guns was made in 1326 by the city council in Florence, who called for the manufacture of cannon.

In the fifteenth century, gunpowder was widely used in Italy, where the design of fortifications was profoundly affected by the end of the fifteenth century.

Gunpowder's Effects on Siege Warfare

The siege--the surrounding and blockading of a fortified position--has been a part of warfare since the beginning of civilization. Famous accounts of sieges in ancient literature include Joshua's toppling the walls of Jericho in the Old Testament and the siege of Troy in the Greek epic poem, The Iliad.

Before the introduction of gunpowder, the defender of a fortress had the advantage militarily, but afterwards, until fortifications were modified to defend against artillery fire, the attacker had the advantage.

The inadequacy of medieval fortifications, which emphasized height rather than strength, was made painfully clear by the victorious march through Italy in 1494 of the French king Charles VIII. His siege train included many powerful cannon, which enabled him to take city after city with a force of only 40,000 men. With gunpowder, invaders no longer needed to pass over walls--they could shoot holes through them instead.

CANNON

Definition

A cannon (same term for plural) is a large gunpowder-powered mounted weapon. It consists of a chamber containing gunpowder next to a tubular barrel from which a projectile is propelled by the sudden release of gas after ignition. Sub-varieties of Renaissance cannon include "hooped" cannon, "bombards," and "mortars."

Cannon are mounted to fixed architectural positions or to carriages, which makes them mobile and better able to absorb the recoil of firing. The choice of platform generally depended on whether they would be used for defending fortresses from the inside or attacking them from the outside.

Construction, Materials, and Transport

The earliest cannon barrels were made of metal wedges held in a circle by hoops and mounted to a bed by metal straps. "Hooped" cannon were succeeded by cannon whose barrels were cast of iron. The larger cannon, called "bombards," were usually cast in several sections to make them easier to transport. On site, the sections were mounted to timber beds.

Because large bombards might weigh 8000 pounds, they were generally pulled by oxen, the strongest but slowest of the draft animals used in Europe. The use of horses to pull the artillery, which enabled it to keep up with the army, contributed to the success of the 1494 invasion of Italy by the French.

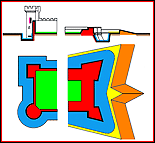

Breech- and Muzzle-Loaded Designs

Early cannon were breech-loaded (loaded from the rear) and closed by various plugging devices. A wedge was usually inserted between the powder chamber and a fixed block at the rear.

Breech-loaded cannon were succeeded by closed-end castings that were loaded through the muzzle. Cast bronze was much safer and could fire a more powerful load than cast iron, but its cost was three times more.

An early form of muzzle-loaded cannon was the mortar. It was short like a single section of a bombard, and its powder chamber was smaller in diameter but proportionately longer.

Projectiles

Although arrow-like missiles were sometimes used, the most common early projectiles were stones that had been carved into spheres.

Metal balls, which were invented by the French, were easier to produce. Because they were smaller than stone balls of the same weight, equal destructive force could be achieved using smaller cannon.

Another advantage of metal balls was that they could be made into incendiary devices by heating them to red hot before firing.

WARFARE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY

Plurality of Political Entities

In the Renaissance, Italy served as a battlefield for several types of conflict. Underlying this strife was the plurality of political entities whose rivalries prevented their standing together against foreign invaders.

Regional Rivalries

The various political entities of Italy continued to fight each other for territorial control as they had for centuries, and struggles between neighbors occasioned much warfare. Over time, the independent city-states tended to be absorbed by the five major political entities of Italy in the Renaissance: the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Florence, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of Naples.

Spanish and French Imperialism

France and Spain fought both each other and resistant cities for control over many parts of Italy. At the beginning of the Renaissance, the Spanish already ruled the Kingdom of Naples, which occupied southern Italy. In 1494 the French marched through Italy to claim Naples, taking cities on the way by siege unless they surrendered. They withdrew the following year after much of Italy united against them.

During the first half of the sixteenth century, the principal antagonists were Francis I (ruled 1515 to 1547) and Charles V (ruled as emperor 1519 to 1556). Francis fought to extend his territory, and Charles fought to establish a land bridge between Spain and Germany because he was both King of Spain and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

The most serious of the foreign incursions into Italy was the Sack of Rome in 1527, in which Imperial troops inflicted much damage on the city and left the pope weakened politically. During the rest of the century, the Spanish increasingly controlled Italy through appointed governors.

Papal Militancy

The Italian popes of the Renaissance, especially Alexander VI, Julius II, Clement VII, and Paul III, fought repeatedly to enlarge the Papal States and expel foreign occupiers. Often, their motives involved securing land for relatives.

Turkish Expansion

The Turks, who had established the Ottoman Empire in 1299, were pushing northwestward into Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. With the aid of gunpowder and powerful cannon that fired large stone balls, Sultan Mehmed (Mohammed) II conquered the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1453. Raids on coastal cities became more frequent, and in 1480, less than three decades later, his incursions into Europe included Otranto on the Italian mainland.

Turkish expansion into Eastern Europe continued until the Turks were decisively defeated at sea at the Battle at Lepanto in 1570, which marked the turning point of Europe's efforts to repel the Turks.

THE "TRACE ITALIENNE"

Introduction

Italian medieval defensive features, which were designed to repel attackers who used mechanical devices, were rendered obsolete by the introduction of gunpowder. This stimulated Italian fortifications designers to invent a radically different form of fortification known as the "trace Italienne" or the "bastioned trace." A "trace" is a plan.

The transition began in the middle of the fifteenth century and was complete by the middle of the sixteenth century.

Changing Walls

The introduction of gunpowder brought about many changes to the design of walls.

●Walls reduced in height. The height of the perimeter was reduced because strength rather than height prevented destruction by cannon fire. Height offered no advantages because the guns of the time were less accurate when fired downward from high walls, and missed shots rarely damaged secondary targets. When existing fortifications were modified, the heights of walls and towers were lowered.

●Walls widened into ramparts. Masonry walls were thickened into ramparts, mounds made up of earth or rubble, by piling up dirt against the inner facings of existing walls.

●Walls battered at base. The base of the entire perimeter was sloped outward so that invaders next to the wall could more easily be seen and fired upon. A lip called a "cordon" divided the slanted section called the "scarp" from the vertical section above.

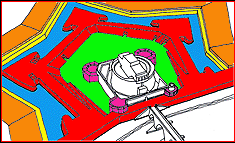

Developing Bastions

Bastions are structures that project from defensive walls and enable men with weaponry to defend the intervening sections of wall and provide cover for the adjacent bastions. Changing the design of bastions was a vital part of the new system.

●Tall towers converted to low bastions. Instead of rising above the level of the walls like medieval towers, the new bastions were the same height as the sections of wall between them. This continuity of level facilitated communication and the moving of troops and munitions from bastion to bastion along platforms behind the parapets. When medieval fortifications were modified, towers were lowered and filled in with earth.

●Circular shape replaced by V shape. Round bastions, which were initially used because curved surfaces deflected indirect hits, left blind spots where the enemy couldn't be reached by flanking fire. This problem was solved by determining the bastion's shape by projecting lines from the firing positions in the flanks of adjacent bastions, which formed arrowhead or wedge-like shapes. Because of their superiority in eliminating blind spots, angled bastions were often added to existing fortifications such as the walls surrounding the Vatican.

●Flanks established on own facings. Positions from which flanking fire could be directed from the side to the area directly in front of the adjacent bastion were established on short, necklike facings extending from the fortress walls.

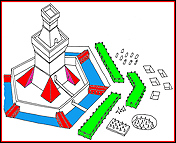

Contouring Land

Contouring the land with ditches and mounds was an important part of the new trace Italienne system of fortifications. Masonry was only used for parts like retaining walls, parapets, and platform roofs.

●Earthen rampart surrounding protected area. The use of earth with walls originated at Pisa in 1500 when it was discovered that adding dirt behind the walls enabled them to withstand artillery fire.

●Ditch surrounding rampart. A deep, wide ditch encircled the rampart. Soldiers trying to approach the walls would be exposed to attack while trying to cross such a ditch. The addition of a ditch also increased the difficulty of tunneling to the walls to blow up a section from underneath. Francesco di Giorgio considered ditches to be a necessity in his treatise on military architecture.

●Firing platform lining ditch. Within the ditch on its outer side was a plateau for soldiers to use for firing.

●Glacis surrounding ditch. Beyond the plateau was a mound of earth called a glacis, which sloped downward at a low angle on the outer side and protected the firing platform. The presence of this mound meant that cannonballs would have to be angled upward to clear it, which lessened their impact. The glacis was developed in the 1520s.

Later Development of Formulaic Approach

Because the angle bastion was based on geometry, the desire to maximize efficiency while minimizing expense led to typically star-like plans of five or more points. Once the logic of a best design was realized, a formulaic quality was inevitable.

Financial Impact

The "trace Italienne" ultimately made warfare more expensive by increasing the cost of fortifications and the number of soldiers necessary to defend or attack them. Because construction could be paid for over time, adding defenses was generally a wise investment. Siena, however, spent itself into bankruptcy building fortifications in 1544.

TRANSITIONAL PHASE

Transitional Versus Later Fortifications

Because of the formulaic approach to fortification design after the trace Italienne was fully worked out, the designs made during the transition were more varied and imaginative than those made later.

Treatises

The subject of fortifications was addressed in several Renaissance treatises on architecture.

In the 1460s Filarete wrote Il trattato d'architettura, which included an ideal city in the form of a star shape based on two squares overlaid.

Francesco di Giorgio focused on the subject of military architecture in Architetture civile e militare (Civil and Military Architecture).

Sebastiani Serlio wrote a work on military architecture late in his career that was subsequently labeled "Book VIII" of his Architettura by Jacopo Strada, a Mantuan antiquarian and art dealer.

Because a number of the drawings found in Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks illustrate weapons such as cannon and mechanical devices, it has been speculated that he had planned to use them in a treatise on military architecture of his own. Leonardo emphasized his own ability as a military engineer when he wrote to Ludovico Maria Sforza, the regent of Milan, concerning employment.

Modifying Existing Fortifications

Because of the impracticality of replacing medieval fortifications, existing structures were usually modified to make them more effective. At Castel Nuovo, advanced firing lines were added twice. Initially, galleries for heavy weapons were added outside the walls while shooters above them supplied covering fire.

Non-angled bastions could be made more defensive by extending the structure into the blind spots.

Development over Time

The development of the trace Italienne began in the middle of the fifteenth century with the use of polygonal towers. Many of its critical features were being used by the turn of the century, but it was not until the second quarter of the sixteenth century that the new system was widely adopted. By mid-century, it was adopted universally across Europe. Knowledge about the new system, whose success was demonstrable, was spread by printed material.

New Parts and Forms

Among the new forms invented in the process of experimentation are capannati, which were important in developing strategic locations from which to fire, and ravelins, which moved the firing positions outward and added strength at particular points.

Important parts of the new trace Italienne system include casemates, blast-resistant vaults from which to fire through embrasures, openings that are tapered to maximize protection for shooters.

The Architects

Among the most important architects who regularly designed fortifications in the Renaissance are Francesco di Giorgio, Baccio Pontelli, three architects of the Sangallo family, and Michele Sanmicheli.

Baldassare Peruzzi, who spent most of his career in Rome working on private and papal commissions, worked on fortifications in his native city of Siena for a seven-year period after building activity had ceased in Rome following the Sack.

Although not regularly employed on military architecture, Michelangelo worked on the fortifications of Florence in 1529 without pay because he was a strong supporter of republican government and wanted to see the city retain its independence from Medici rule. Florence overthrew the Medici after the Sack of Rome left the Medici pope Clement VII powerless until he came to terms with Charles V, who then laid siege to Florence.

FRANCESCO DI GIORGIO'S FORTIFICATIONS

Importance in Fortifications History

One of the most important pioneers of artillery-oriented fortifications was Francesco di Giorgio, who wrote the first significant treatise on the subject, Trattato di architettura civile e militare (1487-92).

Francesco stressed not only the use of effective defensive features but also a layout in which the command centers were connected by efficient lines of communication. Many of the features he built or illustrated in his treatises on fortifications contributed to the development of the trace Italienne.

Features Favored by Francesco

As an architect of the transitional phase, many of the features Francesco designed were refinements to general features that had been used in earlier fortifications. The use of ditches and concentric barriers, for instance, had been mainstays of medieval fortifications.

●Individualization by site. Francesco's fortifications were individualized to address the site's topography and existing architecture.

●Steep scarp. To prevent the inner fortress' walls being scaled, Francesco sloped the lower walls steeply and projected the cordon prominently.

●Ditches. Francesco considered ditches to be vital because they created zones of vulnerability for the attacking infantry, made mining activity more difficult by forcing it deeper, and protected the lower walls from artillery fire. Francesco also favored moats, which were easily achieved when fortresses were located beside rivers or the sea.

●Concentric barriers. Francesco arranged concentric rings of fortifications that enabled lower-level shooters to be covered by higher-level shooters behind them.

●Casemated walls and bastions. Francesco equipped fortresses with casemates, blast-resistant vaults with embrasures for firing artillery. He often built them low into castle walls and on multiple levels in bastions. Having a concentration of firepower compensated for the slowness between rounds.

●Capannati. Francesco utilized capannati, a form of casement that was not built into the walls. He often placed them across ditches and at the corners of strongholds. He placed free-standing capannati in ditches and on platform roofs.

●Variably shaped bastions. Francesco experimented with different shapes of bastions. He liked cylindrical forms because they deflected missiles. Because he also appreciated the viewing advantages of angular bastions, Francesco sometimes used a form that combined features from each by using wide, curving walls that meet in a point.

●Detached forward defenses. Francesco illustrated the building of a variety of obstacles such as pits, fences, and fields of sharp projections outside the ditch. These obstacles forced attackers to fire high and weave through them. He also advocated the use of ravelins, angled or curved sections of wall that shielded bastions or towers from the enemy.

Patrons

Although Francesco di Giorgio designed defenses for sites all over Italy, most of his work was for two patrons. Both were powerful rulers who recognized the need to fund fortification projects generously.

●Federico da Montefeltro. Federico II da Montefeltro commissioned Francesco, who worked on many parts of the ducal palace, to design fortifications in the duchy of Urbino, which was surrounded by land-hungry neighbors.

●King Ferdinand of Naples. King Ferdinand I, who ruled the Kingdom of Naples from 1458 to 1494, employed Francesco to design fortifications because he feared raids from the Turks, who had taken Otranto in 1480. After Ferdinand's death, Naples was taken by the French but regained when Francesco assisted Alfonso II, Ferdinand's successor, by exploding gunpowder in a mine under the walls.

BACCIO PONTELLI'S FORTIFICATIONS

Old and New Features

Baccio Pontelli was influenced by Francesco di Giorgio, whose fortifications around Urbino would have been known to him. He understood the importance of designing bastions individually according to the sites they overlook.

As typical of his day, Pontelli's designs included features that were outmoded or soon would be such as machicolations, tall towers, and circular bastions. His progressive features included outward-sloping lower walls, ditches, low bastions, ravelins, and embrasures.

In 1490, Pope Innocent VIII appointed Pontelli as inspector general of fortifications in the Marches.

Works

In addition to his fortifications at Ostia, Baccio Pontelli is believed to have designed fortifications at Senigallia (1479-1492), Osimo (1487-8), Offida (1488), and Jesi (c. 1488-92).

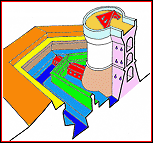

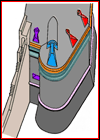

♦Ravelin of Fortress at Ostia, 1483-86. To protect Rome from Turkish raids to coastal cities, Baccio Pontelli was commissioned to build a fortified castle near Ostia, which had been the port of Rome in ancient times. The commission was made in 1483 by Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, who had been appointed Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia that year by his uncle Pope Sixtus IV. The castle, which included a nicely decorated apartment, came to be called the Castle of Julius II because Giuliano also spent time there after he became Pope Julius II. Although medieval machicolations were still used, the angling outward of the lower wall was a modern feature. An especially important modern feature was the use of a ravelin, a separate, freestanding structure outside the fortress walls.

SANGALLO BROTHERS' FORTIFICATIONS

Collaboration of the Brothers

As brothers, Giuliano da Sangallo and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder often collaborated on projects. As the younger, less well-known brother, Antonio often assisted his brother and supervised work in his absence. This was especially true early in his career. The extent of their individual contributions on many shared projects is difficult to determine.

Giuliano's Work on Fortifications

Like other successful architects of the Renaissance, Giuliano received commissions for all types of structures including fortifications, which were much in demand during his lifetime. One of his most noted defensive structures was a bastion at the Fortress of Poggio Imperiale.

Antonio's Specialization in Fortifications

Many of the commissions received by Antonio individually were for fortifications, which were to a large extent, his specialty. He received many commissions to build fortifications from Pope Alexander VI and from the city of Florence.

After the Medici, who had been patrons of the Sangallo family, were expelled from Florence following the 1494 French invasion, Antonio went to Rome and worked for Alexander VI. The principal fortifications work Antonio did for the pope was the conversion of Castel Sant'Angelo into a papal fortress and the building of fortresses along the coast to deter further encroachment by the Turks.

In 1504, shortly after the death of Alexander VI, Antonio returned to Florence where he became chief engineer of fortifications. During the next decade, he tended to specialize in fortifications. In 1518 Antonio moved to Montepulciano.

Antonio da Sangallo worked on a number of fortifications projects over his long career, which spanned around half a century. Among the most admired of the fortresses designed by Antonio are those of Civita Castellana (1499-1501), Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi (1495-1513), Nepi (1499-1501), and Nettuno (1501-3).

Works

The brothers worked both separately and together.

♦Walls at Colle Val d'Elsa, c. 1485, Giuliano da Sangallo. Giuliano da Sangallo designed horizontal "letterbox" embrasures in a pillbox at the Walls at Colle Val d'Elsa.

♦Castel Sant'Angelo, Rome, Antonio da Sangallo the Elder. At the Castel Sant'Angelo, Antonio made a number of changes and additions for Pope Alexander VI that would make it into a papal fortress. He strengthened the defenses by converting Pope Nicholas V's cylindrical corner towers to polygonal bastions. Antonio built a cylindrical tower between the fortress and the bridge, the Ponte Sant' Angelo, to control traffic coming from Rome. He added a moat using water from the Tiber. He also added several features that would enable a besieged pope to take refuge there such as a comfortable apartment, a cistern for the collection and storage of water, storage rooms for provisions, and a concealed passage known as the Passetto di Borgo, which ran along the top of the Leonine Walls. The remodeling of the interior included a prison that had a special cell block for important prisoners such as the pope's political enemies.

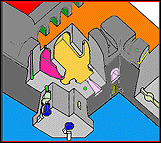

♦Bastion at the Fortress of Poggio Imperiale, near Poggibonsi, 1495-1513, Giuliano da Sangallo and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder. The Sangallo brothers constructed the Fortress of Poggio Imperiale, which was built to protect Florence. The fortress was located on the main road into Florence from Siena.

♦Fortress of Nettuno, 1501-03, Giuliano da Sangallo and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder. Giuliano and Antonio built the Fortress of Nettuno. Its bastions included both progressive features such as curved shoulders and obtuse-angled points and dated elements such as the decorative frieze.

BALDASSARE PERUZZI'S FORTIFICATIONS

Work in Siena

Baldassare Peruzzi, who principally worked in Rome, came to work on the fortifications of his native city of Siena following the Sack of Rome, during which he was imprisoned and held for ranson. The Sienese government paid his ransom and commissioned an overhaul to the city's dated defenses.

From 1527 to 1533, he revolutionized the city's defenses by building five new bastions to guard gates where parts of the topography left the city vulnerable to attack.

♦Bastions of San Viene, Camollia, and Laterina. The best-preserved of Peruzzi's new bastions stand near the gates of San Viene, Camollia, and Laterina. (Peruzzi's fortifications at Siena are the subject of the next page.)

ANTONIO DA SANGALLO THE YOUNGER'S FORTIFICATIONS

Training and Experience

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger was trained as an architect and military engineer by his uncles Giuliano and Antonio da Sangallo, who were both on the cutting edge of fortifications design around 1500.

Antonio received many commissions for fortifications during his career. His reputation as a military architect led to Clement VII's assigning him, along with Michele Sanmicheli, to survey the fortifications of castles in the Papal States in 1526.

Works

♦Fortress stage of Villa Farnese, Caprarola, c.1521. Early in his career, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who later became Paul III, commissioned Antonio and Baldassare Peruzzi to design a fortress at a family property at Caprarola. They designed the villa's pentagonal perimeter, but its exterior detail and interior were designed by its subsequent architect Vignola, who left the moat dry and used the platform roofs of the bastions as terraces.

♦Fortress Michelangelo, Civitavecchia, completed 1535. The Fortress Michelangelo was begun under Pope Julius II by Bramante to secure the port city of Civitavecchia, and it was completed under Pope Paul III by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. This fortress is significant for achieving the first complete enceinte (belt of walls and bastions) using aspects of the new approach. The octagonal tower at the center on the harbor side reflects the new use of angular bastions, but the round bastions on the corners reflect the fortress' having been begun before angled bastions were in use. The fortress is named for Michelangelo, who made an addition to the tower in the center.

♦Fortezza da Basso, Florence, 1534. One of Antonio's most impressive fortresses is the Fortezza da Basso in Florence. It was commissioned by Pope Clement VII's illegitimate son, Alessandro de' Medici, who governed Florence as a duke. (His rule had been sponsored by Charles V, whose imperial forces besieged and took Florence in 1529-30 as part of a deal between the emperor and the pope.)

♦Rocca Paolina, Perugia, 1540-43. The Rocca Paolina in Perugia was commissioned by Paul III, who felt triumphant at having finally taken Perugia into the Papal States. The city had fought hard over the years to maintain its independence, which had been compromised already by both the French and other popes. The fortress was despised by the citizenry because it symbolized their loss of liberty, and when the old order fell in the nineteenth century, it was destroyed.

♦Double Bastion at Porta Ardeatina, Rome, 1535-42. Antonio da Sangallo the Younger designed the Bastions at Porta Ardeatina as part of a new beltway around Rome for Pope Paul III. The pope wanted to improve Rome's defensive capacity, whose inadequacy had been demonstrated by the Sack of Rome in 1527. The doubling of the flanks and faces dramatically increased the number of gun emplacements possible, and this bastion could accommodate sixteen heavy weapons and eight lighter ones. A raised gun platform called a cavalier stood above the open deck, which was also a gun platform. Casemates below allowed greater protection for the artillery men. To prevent the enemy from tunneling below the walls, listening posts were established underneath the ditch. Soldiers with listening horns occupied horizontal shafts that were reached through well shafts. Flues above the vertical chambers ventilated the shafts.

MICHELE SANMICHELI'S FORTIFICATIONS

Origin and Early Career

Michele Sanmicheli, who was born in Verona, was one of the most experienced military architects of the sixteenth century. Vasari credited him with the invention of the angle bastion at delle Maddalene in 1527, but this bastion has now been attributed to Michele da Leone.

During his eighteen years in Orvieto, Sanmicheli often worked as a military architect. For Pope Clement VII, he worked on fortifications for Parma and Piacenza and assisted Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in inspecting the fortifications of the cities in the Papal States in 1526.

Employment by the Venetian Republic

By the end of 1526, Sanmicheli returned to his native city of Verona and began modernizing the city's fortifications by adding angle bastions. Verona was then part of the Venetian Republic, and its location southwest of Venice made it the first line of defense against attack on the mainland.

By 1530, Sanmicheli had been engaged by the Venetian Republic to work on fortifications, and in 1535, he was officially put in charge of the fortification of all Venetian possessions on both the mainland and in the Mediterranean.

To visit the fortifications of Venetian possessions, Sanmicheli traveled extensively in the Mediterranean and may have been the only Italian architect of the sixteenth century to have seen the architecture of Greece.

Inspection Tours

Notable among Sanmicheli's inspection tours of the fortifications of Venetian possessions are the following:

●1531: Mainland. With the Commander-in-Chief of Venetian forces, Francesco Maria della Rovere, Sanmicheli visited the fortifications of Venetian territory on the mainland.

●1534: Dalmatia. In 1534, Sanmicheli inspected the fortifications of Venetian territory in Dalmatia, across the Adriatic from Venice.

●1537-40: Adriatic and Aegean. Sanmicheli traveled in the Adriatic and Aegean Seas, reaching Crete, which was then called "Candia."

●1550: Adriatic. Sanmicheli toured Venetian holdings in the Adriatic.

Style

Sanmicheli's gates conveyed a refinement that was in accord with views expressed by Venice's general commander, who had criticized Venice's gates for representing the brute force associated with dictatorships rather the civility associated with republican governments.

Sanmicheli created an impression of solidity and impregnability in designing gates by organizing rusticated walls into planes overlaid with rusticated columns carrying an entablature. He favored the simplest, heaviest order, the Doric, and he typically bracketed half-round columns by placing pilasters or square columns on the ends.

Works

During his employment as the chief military architect of the Venetian state, Sanmicheli designed fortifications at a number of sites. He also designed city gates, which are presented on the screen devoted to public buildings.

♦Fortezza di Sant' Andrea, Lido, Venice, 1535. Fort St. Andrew stands at the entrance to the lagoon, the most strategic of all locations. Long wings containing gunports in both directions made it impossible for Turkish invaders to reach the city. At the center is a majestic three-bay portal. Its lower story, like Sanmicheli's gates, features rustication arranged in several planes. The Doric colonnade, which is outermost, is followed by the arcaded plane, and finally, by the blind arches of the innermost plane. The upper story serves as a lookout tower. Its brick construction forms a contrast in color and texture that sets off the stone heraldic emblems, inscription, and lion relief. The lion has significance to Venice because it is the emblem of the city's patron saint, the Evangelist St. Mark.

(Author's note: The devotion of the next page to Baldassare Peruzzi's fortifications at Siena is a reflection of the availability of illustrations of this site rather than of his being more important than the other military architects.)

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back