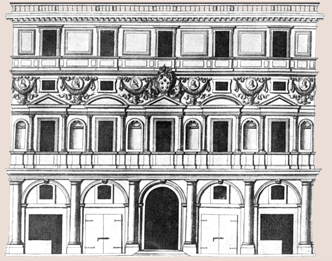

Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila

Rome, begun 1518-20

Architect: Raphael

BACKGROUND

Commission

Giovan Battista Branconio dell' Aquila commissioned Raphael to design the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila in Rome around 1518.

Location in the Borgo

The palace was located along the Via Alexandrina in the Borgo, the area between the Vatican and Castel Sant' Angelo.

Also located in the Borgo was the Palazzo Caprini, which had been designed by Bramante and now served as Raphael's own residence.

Destruction of the Palace

Like the Palazzo Caprini, the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila was torn down in the seventeenth century to make way for a colonnade to form a new piazza in front of St. Peter's.

Because these palaces were destroyed, they are known only through sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drawings and other documentation.

INFLUENCE OF THE ANTIQUE

Departure from the Palazzo Caprini Type

Although the Branconio palace was like Bramante's Palazzo Caprini in its use of basic features and architectural forms, it differed in more important ways such as the treatment of columns.

Antiquarian Perspective

Both Raphael and his patron, Giovan Battista Branconio, were early antiquaries, proponents of antiquarianism. They studied ruins, coins, inscriptions, and other physical evidence of the ancient past. In his capacity as Leo X's architect in charge of antiquities, Raphael had advocated preserving ancient buildings and recording their appearance through drawings.

Raphael's design of the façade of the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila exhibits a number of significant innovations that increased its similarity to antique architecture in both appearance and spirit.

Absence of Rustication

The most noticeable and radical of Raphael's innovations at the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila is the absence of rustication, a feature that was traditionally used on palace ground stories as a holdover from medieval times, when fortification was necessary.

As the first palace of the Renaissance to lack rustication, the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila began a new trend in the design of palace façades. In this, the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila made a break with the highly influential Palazzo Caprini.

Presence of Orders on Ground Story

Coupled with the absence of rustication on the ground story is the presence of story-high engaged columns of the Doric order, which stood between the arches. Raphael's usage of story-high engaged columns, which separate the arches framing individual shops, is more expressive of the building's internal structure than Bramante's usage of them to mark the bays on the piano nobile of the Palazzo Caprini, which fronted continuous spaces such as the salone.

These columns may have been meant to continue the motif of a colonnaded entranceway. The use of colonnades to surround forums or line entrance corridors was recommended by Vitruvius, as Raphael would have known.

According to a biography of Pope Nicholas V by Giannozzo Manetti (1396-1459), a colonnaded entranceway through the Borgo to the Vatican had been planned in the previous century. The engaged columns on the ground story of the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila would have continued the colonnade motif if such a project were to be revived.

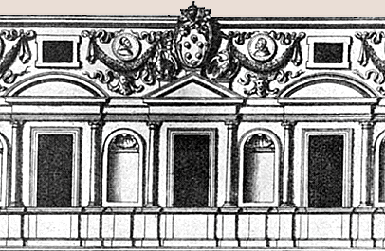

Stucco Relief

Paralleling Bramante's invention of an aggregate of stucco and marble powder to make a cheap and effective imitation of rusticated stone, Raphael invented a mixture suitable for forming elaborate relief sculpture. This enabled him to create rich effects like those he admired from antiquity.

INVENTION AND IRREGULARITY

Mannerist Qualities

More than any other building by Raphael, the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila exemplifies his departure from the rational classicism of Bramante and heralds the tendency to invent novel ways of using architectural forms, a tendency that evolved into the style known as Mannerism.

Violations of Classical Principles

On the façade of the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila, some of the traditional principles governing classical architecture were violated.

=Using niches above columns. The classical principle of placing supports over supports and openings over openings was violated by the use of niches above columns, which created an interplay between the columns' convexity and the niches' concavity.

= Staggering similar features. The traditional vertical alignment of similar features was violated by the staggered arrangements of the columns with the colonnettes and of the arches on the ground story with the apsidal niches on the piano nobile.

=Using independent sections of the entablature. Unlike the sections of entablature above the windows, which appeared to be carried by the columns below them, the sections of entablature spanning the wall between the windows were independent of a system of construction involving the orders.

=Ambiguity of parts. Clarity and order are lost due to the crowding of both the architecture and the ornament. The relationship and identities of the parts of the Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila were ambiguous because they were crowded together. A band of stucco ornament connected the upper stories. On both stories, the bands of wall below the windows were broken in plane in correspondence with the features above.

=Alternating triangular and segmental pediments. Another of Raphael's novel combinations of forms is the alternation of triangular and segmental pediments over windows, which he also used at the Palazzo Pandolfini in Florence. This alternation had precedent in the interiors of such ancient Roman buildings as the Pantheon and the Temple of Venus and Rome, which were built after Vitruvius set forth the principles that Renaissance architects regarded as classical.

ORNAMENTAL SCHEME

Art Forms

In addition to the ornament provided by the orders and other architectural detailing, there is a full scheme of enrichment by art.

●Sculpture in niches. The apsidal niches between the windows contained sculptures, which would have carried the lines of the columns upward visually.

●Stucco relief. Relief ornament was used autonomously over much of the surface instead of only in places where it appeared to articulate the structure. It spreads out to fill all the available wall space, and in the center, it extends up in front of the upper story. The ornament includes classical motifs such as fluttering ribbons and festoons. The presence of eagles, aquilis in Italian, refers to the patron's home town of Aquila.

●Portrait medallions. Within the dips of the garlands are medallion containing portraits. The use of medallions, which resemble giant coins, refers to the owner, Giovan Battista Branconio, who was a numismatist, a student and collector of coins. He and Raphael shared a common interest in antiquarian matters, and their portraits faced toward the coat-of-arms in the center.

●Medici coat-of-arms. At the top center of the relief ornament was the Medici coat-of-arms, which is identifiable from the palle. Consent to display it would have come from the Medici pope Leo X, who employed Giovan Battista Branconio as privy chamberlain.

●Panels containing marble or fresco paintings. Between the windows of the top story were square panels that probably contained colored marble or fresco paintings of narrative content.

Emblematic Character of Assemblage of Ornament

Taken as a whole assemblage, the images are emblematic of the patron's identity and interests.

The abundant use of ornament gave the façade a festive appearance as if it were hung with temporary decoration for a special occasion.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back