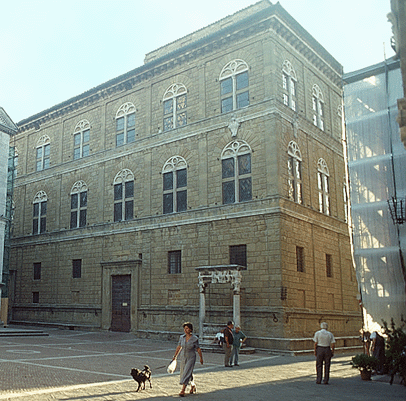

Palazzo Piccolomini

Pienza, 1459-62

Architect: Bernardo Rossellino

BACKGROUND

Commission

The Palazzo Piccolomini was commissioned by Pope Pius II of the Piccolomini family as part of a project to make an ideal city of his native town of Corsignano, which he renamed Pienza.

The Pope, who had strong views concerning the project's design, selected Bernardo Rossellino as the architect for this project.

Importance

The Palazzo Piccolomini was important in the history of palace design for its early use of pilasters. These classical features were first seen in domestic architecture on the façade of the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. By the end of the fifteenth century, pilasters were also utilized on palace façades in Rome.

Orientation

The palace's main entrance faces the street rather than the piazza, from which there are two secondary entrances.

COMPARISON WITH RUCELLAI PALACE

Linkage to the Palazzo Rucellai

Bernardo was familiar with the façade of the Palazzo Rucellai because he supervised its construction. Although Alberti is traditionally credited with the design, some architectural historians consider Bernardo to have been its architect.

Features Common to Both Palaces

The two palaces share several similarities.

=Pilasters carrying entablatures. The façades of both palaces are articulated on all three stories by pilasters carrying string courses detailed as entablatures.

=Smooth rustication. The masonry on all three stories of both palaces utilizes smooth rustication in which dressed stone is laid with prominent joints.

=Base detailed as pedestals of pilasters. The bases of both palaces include the detailing of pedestals under the pilasters, but the detailing of the Palazzo Piccolomini is less distinct. (Alberti used bases to adjust column heights so that columns could be proportioned in accordance with their individual orders regardless of the heights of the individual stories.) The benches and hitching rings are features that were common to other palaces as well.

= Vertically aligned windows. The windows of both palaces are aligned vertically, unlike many other palaces at mid-century. The windows of both, like most fifteenth-century Florentine palaces, were rectangular on the ground story and biforate on the upper stories.

Differences from the Palazzo Rucellai

Several features distinguish the Palazzo Piccolomini from the Palazzo Rucellai.

●Wider window spacing and less enframement. The windows are further apart on the Palazzo Piccolomini than on the Palazzo Rucellai, and the masonry around them is treated differently. On the Palazzo Rucellai the windows appear to have frames because the stones along their sides are uniform in width, forming a columnar grouping, but on the Palazzo Piccolomini, the blocks framing the windows vary in width because they are part of the bond.

●Rustication of ground-story pilasters. The pilasters on the ground story of the Palazzo Piccolomini are rusticated, which makes them blend in with the wall rather than stand out like the smooth ashlar pilasters on its upper stories and on all three stories of the Palazzo Rucellai. This gives the lower story a coarser texture than the stories above, which was quite common on Renaissance palaces.

OPEN-AIR FEATURES

Courtyard

The courtyard loggias vary in depth on the different facings. The entrance wing facing is slightly deeper than the side facings, and the loggia on the rear is around twice as deep as those on the sides.

The courtyard is enclosed on three sides by wings containing rooms and on the fourth side by an outward-facing loggia.

Garden Loggias

The Palazzo Piccolomini has loggias on all three floors of the garden facing. These loggias, especially the highest one, provide a view of not only the garden but also the distant countryside. The pope was fond of this view and specified the palace's placement and use of loggias with it in mind.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

|

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back