Leon Battista Alberti

1404-72

LIFE

Birth

Leon Battista Alberti was born in Genoa. He was the illegitimate son of a member of an important Florentine family that had been banished from Florence since 1402.

Education

Alberti began his education in Genoa, then studied at the University of Padua, and finally took a doctorate in canon law in Bologna. He took holy orders in 1432, and for much of his career, worked as a papal secretary.

Alberti's Humanist Outlook

Like many of his contemporaries, Alberti was a humanist. He had a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature, history, mathematics, science, and philosophy. When he was only twenty, he wrote an imitation of a Roman comedy that passed as genuine.

Like the ancient writers he studied, Alberti regarded Nature as man's most important teacher. He believed that rational principles guided all human activity from politics to painting.

Periods in Florence

Alberti's interest in the arts and his ideas about artistic practices were much influenced by the time he spent in Florence. He may have stayed there briefly in 1428 to take care of family business after the order of banishment had been lifted from his family.

He returned for a 2 1/2-year stay in 1434 when the pope he served, Eugene IV, left Rome to establish an alternate base of the papacy after being deposed by a Church council. Other visits continued over the years.

In Florence, Alberti developed dynamic relationships with the leading artists, who were then formulating the new style. He dedicated Della pittura, the Italian-language edition of his Latin treatise on painting, to them.

Travels and Influence

Although much of his life was spent in Rome, at times, his duties included missions to other Italian cities like Bologna, Venice, Ferrara, and Mantua.

Through both his own family background and his employment as a papal secretary, Alberti was acquainted with many rich and powerful families ranging from ruling families like the Gonzaga and Malatesta to commercially based families like the Rucellai in Florence. He affected the course of architecture through advising them on matters of patronage and designing buildings for them. Because these buildings were located in many parts of Italy, their influence on later architects was widespread.

Residence in Rome

During periods when Alberti was living in Rome, he was able to study ancient Roman buildings and ruins.

As a papal advisor, Alberti was able to become involved with plans for rebuilding the city, restoring Old St. Peter's, and expanding the Vatican complex. Although no important buildings in that city can be positively attributed to Alberti, his impact on late-fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Roman architecture is incalculable.

TREATISES ON ART

Overview

As a humanist, Alberti wrote treatises on many subjects during his long career, including one on the family (Della famiglia), which he considered the building block of a moral and rational society. His treatises on painting, sculpture, and architecture had a tremendous effect on the subsequent development of these arts.

De pictura (On Painting)

Alberti wrote his treatise on the art of painting, De pictura, in Latin in 1435. The following year he published his own Italian translation, which had minor deletions of the more arcane parts. He called it Della pittura and dedicated it to the leading artists in Florence: Brunelleschi, Donatello, Ghiberti, Luca della Robbia, and Masaccio.

.

Book I: The first book is entirely devoted to the subject of geometry and one-point linear perspective. Alberti began with the importance of reason, concluding that geometry is the rational basis for painting. The painter's goal is moral teaching through the imitation of Nature. Because Nature is best understood by means of mathematical principles, the painter must learn these principles. In this book Alberti explained the theory of linear perspective, which was widely used in the later-fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Books II and III: The second and third books of De pictura focus on design and the education of the artist, respectively. According to Alberti, the most important kind of painting is historical narrative, which he termed istoria. Citing many Greek and Roman authors, he identified istoria with morality and piety because both, he claims, are the offspring of religion.

De statua (On Sculpture)

Although De statua, Alberti's treatise on sculpture, was probably written around the same time as De pictura, it was not published until around 1464.

Because it was not translated, it was less influential.

De re aedificatoria (On Architecture)

As the first architectural treatise of the Renaissance, Alberti's De re aedificatoria (discussed later) had a decisive influence on Renaissance architecture.

ALBERTI THE ARCHITECT

Relationship to Construction

Although he was not an architect by profession, Alberti, who first turned his attention to architectural design in the 1440s, enjoyed a different relationship with the patron and site than other architects at that time.

Alberti supervised construction by means of supplying drawings and instructions and maintaining correspondence with the builders. In the course of such correspondences, he stressed the importance of adhering to the specified proportions.

Sources of Influence

Alberti's opinions about architecture were influenced by several sources.

1.Roman Architecture. Alberti was profoundly influenced by Roman architecture. He studied ancient ruins in Rome and at other ancient sites in Italy, not with an eye to their construction, as Brunelleschi had, but in order to decipher basic architectural principles. (His own work more closely resembled the architecture of ancient Rome than did any other architect's work since antiquity.)

2.Vitruvius' Treatise. Alberti was also influenced by Vitruvius' treatise on architecture, which was recovered in the fifteenth century when scholars were eagerly seeking ancient manuscripts. It was especially valued by architects in the Renaissance and later because it was the only work on architecture to survive from antiquity. Alberti was particularly influenced by its material on proportion and the orders.

3.Tuscan-Romanesque Architecture. Like others of his time, Alberti misunderstood the place in architectural history of local Italian Romanesque buildings like San Miniato al Monte and the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, which utilized certain classical forms like the column, round arch, and pedimented window frame.

4.Contemporary Florentine Architecture. Alberti recognized and admired the achievements of Brunelleschi and others in founding a new direction in architecture that coincided with the new humanist outlook. (The fact that Pope Nicholas V and Pope Pius II employed only Florentine architects was probably due to Alberti's influence.)

DE RE AEDIFICATORIA

When Written and Published

Alberti seems to have begun writing his treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria (On architecture), in the 1440s. Although a substantially complete version was shown to Pope Nicholas V in 1452, it was not published until 1485. Handwritten copies, however, were circulated among Alberti's circle of acquaintances.

Influence

Alberti's treatise greatly influenced the course of Renaissance architecture, especially with regard to the orders and the design of churches. His treatise on architecture was translated and published in England and France during periods of classical revival, when Alberti was revered.

Approach to Civic Architecture

Alberti viewed architecture as a practical combination of science and moral philosophy. He began his treatise with issues that affected entire cities such as its climate and roads. He believed that for the city to be unified, it was necessary for the various types of architecture to work together.

Similarity to Vitruvius' Treatise

Alberti's treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, was so similar to Vitruvius' De architectura libri decem that it has been speculated that Alberti initially intended to produce a more literate version of it with a commentary.

In form, both were called On Architecture, written in Latin, and divided into ten books.

In content, both named the concepts of strength, utility, and beauty as the elements of architecture. Both embraced the ancient notion that harmony and proportion are linked; and both defined harmony, a key ingredient of beauty, in terms of the relationship between the parts and the whole. Vitruvius called this quality symmetria, and Alberti called it concinnitas.

Theory of Beauty

At the core of Alberti's philosophy of design was his theory of beauty.

Albert believed that beauty depended on "a harmony and concord of all the parts, achieved in such a manner that nothing could be added, taken away, or altered except for the worse." This quality is called concinnitas.

The creation of harmony required mirroring nature's physical laws in the number (numerus), the placement (collocatio), and the proportions (finitio) of the parts.

The number and relationships of the parts to each other should be organic like the body, which has a center from which extensions on one side are balanced on the other in form, number, and placement. A basilica, for instance, conforms to this principle in having a central nave, crossing, and apse from which extensions such as transept arms and chapels project on each side in a symmetrical manner.

Proportions should follow nature. Like the ancients, Alberti believed that an underlying order in the universe was demonstrated by the correspondence between certain whole-number ratios and musical harmony, forming a harmonic proportion.

Ornament

Alberti distinguished between beauty and ornament, which together determined a work's aesthetic quality. Beauty, whose foundation was concinnitas, was intrinsic to a building's design.

Ornament, according to Alberti, was "an auxiliary brightness and complement to beauty." That Alberti did not consider ornament and structure to be mutually exclusive categories is suggested by his belief that the column is "the principal ornament of architecture" (VI.xiii).

Canon of Five Orders

Alberti attempted to clarify Vitruvius' description of the parts and proportions of the orders, which like many parts of the treatise, was vague and error ridden from generations of re-copying.

Because Vitruvius wrote his treatise more than three centuries before the end of the Roman Empire and at a time when some architectural elements, such as the composite order, were still developing, the composite order is not included in his treatise. It was first used for public architecture on the Arch of Titus.

What has become the canon of five orders originated in Alberti's treatise with his attempt to incorporate the evidence of ancient buildings, which included the composite order.

Churches

Alberti discussed churches under the category of "Temples," thereby linking them with the sacred buildings of the Classical tradition. He described a number of qualities and features he considered desirable for church design.

Alberti's first requirement for churches was that they embody beauty, which he defined in terms of harmony and proportion.

Churches also were to be elevated from their surroundings, and were to incorporate a portico into their façades. Alberti also considered the centrally planned church to be ideal, and recommended nine geometrical forms for churches, all of which were based on the radius of a circle.

Although it lacks a classical entrance portico, Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria delle Carceri incorporated many of the qualities and features for churches that Alberti described.

THE COLUMN'S ROLE

Overview

One of the central issues associated with Alberti's theories is the role of columns. He wrote that "a row of columns is nothing else but a wall open and discontinued in several places." (I.x) His view of columns was conditioned by his limited view of their place in architectural history.

Columns in Classical Architecture

Like Brunelleschi, Alberti had no knowledge of the Greek architectural tradition or the Roman debt to it. In misunderstanding the evolutionary context of Roman architecture, Alberti could not appreciate the extent to which it departed from its origins.

The Greeks used trabeated construction in which columns were sculpturally conceived, independent, structural units. The hollow cores formed by the peristyles of many ancient-Greek temples still stand despite the absence of solid walls.

The Romans used arcuated construction in which columns functioned primarily as embellishments to walls and arcades. They were also used in their original freestanding form for porticos.

Columns in Tuscan-Romanesque Architecture

Alberti misunderstood the relationship of Roman architecture not only with its Greek predecessor, but also with its Tuscan-Romanesque successor. The gap between these two earlier styles was greater in both style and years than Alberti had thought.

On Tuscan-Romanesque buildings, columns were used without entablatures, and instead, were used to carry blind arches.

Rejection of Arcade and Colonnade Combination

Unlike Brunelleschi and Michelozzo, Alberti considered columns to be ornamental rather than structural supports, and thus did not incorporate arches supported by columns into his architecture.

Use of Pilasters instead of Engaged Columns

In his early work, Alberti used engaged columns to embellish walls, but in his later work, he used flat pilasters. It has been proposed that he found an inherent contradiction between the three-dimensional character of the column and the flatness of the wall.

STYLISTIC CHARACTERISTICS

Overview

Although Alberti's style evolved over his three decades of work in architecture, certain generalizations can be made about his style.

Orders on Façades

Alberti was the first architect to articulate church and palace façades with the orders. He initially used engaged columns but later preferred pilasters. He was also the first to articulate the stories by superimposing colonnades one over another in an arrangement referred to as supercolumnation.

Free Use of Classical Forms

Alberti believed that with sufficient understanding of the vocabulary and principles of ancient architecture, it would be possible to invent new forms and combinations that maintained the Classical spirit.

●Invention of capitals. In his early work, Alberti invented new capitals using the motifs and compositional principles of Roman capitals.

●Combining pilasters with rustication. At the Palazzo Rucellai, Alberti combined pilasters with rustication.

●Use of triumphal arch and temple front. Alberti's church-façade compositions incorporated Roman building types like the triumphal arch and the temple front. At Sant' Andrea, he utilized both of these forms together.

Piers Supporting Arcades

Alberti used piers instead of columns to support arches for two reasons. He observed this usage on Roman models, and he perceived an incompatibility between the circular quality of the column and the flat plane of the arch. The use of arcades carried by massive piers gives Alberti's work a monumental quality not found in the work of his contemporaries.

Columns Ornamenting Piers

Although it is unclear who designed the first Renaissance structures using columns to ornament piers, Alberti is considered the inspiration for this form, which originated in ancient Rome and could be seen on such buildings as the Theater of Marcellus and the Colosseum. The first Renaissance structures using this form were the later destroyed Benediction Loggia of the Vatican and the unfinished courtyard of the Palazzo Venezia in Rome.

Lighting to Create Mood

Alberti's placement of skylights and windows was designed with an eye to how light would eventually be distributed in the interior.

In churches, Alberti placed windows high to provide a view of the sky instead of the city in a belief that this would inspire thoughts of the celestial rather than of the earthly realm. He preferred dim lighting, which he believed to be more conducive to religious experience.

ARCHITECTURAL WORKS

Overview

Although only two of Alberti's five major works were whole buildings, all of them had enormous influence on later architecture. Their being located in several parts of Italy widened Alberti's sphere of influence.

♦Malatesta Temple, Rimini, begun 1450. Alberti enlarged the medieval church of San Francesco in Rimini, which is popularly known as the Tempio Malatestiano, meaning the Malatesta Temple. His transformational scheme was not completed, but much of its original design is known from a medal illustrating a dome as wide as the rest of the church. The completed work consists of an outer shell that remains unfinished on the upper story of the façade. The Malatesta Temple is the first church in the Renaissance to incorporate the orders on its façade. Alberti used superimposed orders on the high central section of the façade, but was unable to repeat their use on the corners because of the lower level of the roof there. The façade's lower story was based on the Roman triumphal-arch form, and its side walls are formed of massive arcades like those of Roman structures such as the Basilica Julia.

♦Palazzo Rucellai, Florence, façade c. 1450-64. The Palazzo Rucellai is the first Renaissance palace to include the orders on its façade. They are superimposed in a variation on the Roman Colosseum. Its distinct capitals were Alberti's own invention. Many of the façade's features suggest both local Florentine influence and Roman influence. After the Rucellai family acquired additional property, the palace was expanded by two bays, which compromised its symmetry. The palace's influence was greater outside Florence than in the city itself because Florentine tastes in the fifteenth century tended toward the use of graduated rustication.

♦Santa Maria Novella, Florence, begun c. 1458. The presence of pre-existing features on the lower portion of Santa Maria Novella restricted Alberti's ability to give it a purely classical façade. To maintain continuity with the old part, Alberti covered the new addition with more patterned marble. He called attention away from this anachronistic treatment by imposing a classical framework using a temple front on the upper level and suggesting a triumphal arch on the lower. Because of the proximity of the side portals to the nave arcade, it was impossible to use engaged columns under the outer pilasters of the upper story. Several features of the church's design show the influence of Tuscan-Romanesque architecture. The use of scrolling fins to cover the side-aisle roofs was copied by later churches like Sant'Agostino (1479-83) and Il Gesù (1568-84). A scheme of simple proportions unifies the façade into a harmonious whole.

♦San Sebastiano, Mantua, 1460. San Sebastiano, Alberti's only centralized church, is the first church of the Renaissance to be based on a Greek-cross plan. Many of the building's proportions were based on the ratio of 3:5, which approximates the golden ratio. Two decades later, the church was completed under an architect who did not have Alberti's plan or understand classical design principles. Changes include a groin vault instead of a dome at the center and a dog-leg staircase on the side instead of a single wide flight at the front, as Alberti probably intended. It has been theorized that he also probably intended to have six, regularly spaced pilasters. During twentieth-century renovations, flights of stairs were extended forward from the side bays of the vestibule at the front.

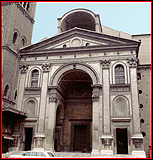

♦Sant' Andrea, Mantua, 1470. Sant' Andrea is especially important for its use of chapels instead of side aisles to flank the nave, piers instead of columns to support the nave arcade, and a barrel vault instead of flat construction attached to the trusses to form the ceilings of the nave and choir. The façade, which is lower and narrower than the body of the church, functions as an entrance vestibule. Its design fuses a triumphal arch with a temple front and includes a second system of the orders. The façade and nave arcade correspond to each other in the sizes and shapes of their openings, the division of the vertical expanse into three levels, and the intersecting of large barrel vaults with small ones.

♦Tribune of Santissima Annunziata, Florence, 1470. Because of the Gonzaga family's financial involvement in the Tribune for Santissima Annunziata in Florence, their favorite architect, Alberti, was called upon to revise Michelozzo's original plans.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back