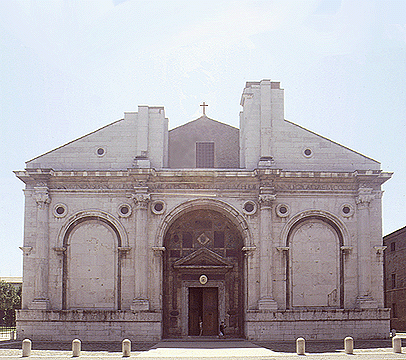

Malatesta Temple

(Tempio Malatestiano)

Rimini, begun c. 1450

Architect: Alberti

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Patron and Project

Alberti designed a new exterior for the Church of San Francesco for Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta (1417-68). San Francesco was the family church of the Malatesta family, the rulers of Rimini. A chapel inside was dedicated to Saint Sigismondo, the family's patron saint.

The Church's Mortuary Function

The Church's function as a repository for the Malatesta family tombs was expanded to include the tombs of a number of distinguished humanists of Sigismondo's court. Their tombs were to be located in exterior arches along the sides of the church, and those of Sigismondo and his mistress Isotta, who later became his wife, were to have been placed in the front. (The placement of tombs in the exterior arches of churches dates to medieval times.)

In the course of construction, the burial places of Sigismondo and Isotta were changed to the interior, and their tombs were accentuated by sculpture.

Sigismondo's Excommunication

In 1459, Pope Pius II excommunicated Sigismondo and stripped him of part of his territory.

The Pope's complaints included Sigismondo's filling the church with pagan images from antiquity, which changed its focus from a celebration of the glory of God and St. Francis to a celebration of the power and taste of its patron.

Pius' conflict with Sigismondo was also conditioned by stories of the latter's participation in political intrigue and various acts of personal immorality including the murder of his wife.

After this time, Sigismondo's political fortunes declined.

CONSTRUCTION

History

Work began on the remodeling of the interior in 1447.

By 1450 Alberti had come to the project and designed the exterior.

After Sigismondo's excommunication in 1459, work on the Malatesta Temple slowed, and in 1461, it ceased altogether. Little past the ground story of the exterior shell had been completed at that time.

Materials from Other Churches

The patterned marble incorporated into the façade around the portal had been removed from Medieval churches in nearby Ravenna such as Sant'Apollinare in Classe.

On-Site Supervision

Alberti wrote directions for Matteo de' Pasti, who supervised the building's construction. He stressed the importance of adhering to the specified measurements and made a clay model of a capital of his own design, a variant of the composite order, for the sculptors to follow.

Remodeling of the Interior

The remodeling of the interior, which preserved the Gothic character of the original church, was carried out by Matteo de'Pasti, and its design is generally attributed to him. Alberti has also been cited as a possible designer of the interior, although this is unlikely considering his preference for Classical over Gothic architecture.

Sculpture

The sculptural ornamentation was carried out by Agostino di Duccio.

BASIC DESIGN

Arcaded Shell Around Old Church

Structurally, Alberti's addition to San Francesco was a free-standing shell formed by an arcaded lower story measuring three vaults wide and seven vaults long.

The Malatesta temple was the first building in the Renaissance whose exterior reflected an understanding of the plasticity of Roman architecture. Alberti's plasticity is illustrated by a number of features on the façade.

Features that were Unfinished or Not Built

When the project was abandoned, the exterior was unfinished, and several major features that had been planned were not built.

●Upper story of façade. The decoration of the upper story of the façade remains incomplete.

●Dome over apse end. A gigantic dome spanning the building's full width at the apse end of the original church had been planned.

●Barrel-vaulted ceiling. On the inside, a barrel-vaulted ceiling built of wood had been planned. It would have formed an inner shell over the nave and hidden the original timber trusses.

DESIGN ACCORDING TO 1450 MEDAL

The Medal

Alberti's original conception of the Malatesta Temple can be envisioned from a medal cast in 1450 by Matteo de' Pasti.

Dome across Rear

The façade is silhouetted by a giant dome at the rear.

Arch over Central Columns

The upper wall is articulated by a pair of pilasters that are connected at the top by a semicircular arch. In the actual construction of the unfinished upper level, pilasters instead of engaged columns were used.

Segmental Half-Pediments

The upper stories of the side aisles were originally conceived as segmental half-pediments, whose curves would have echoed those of the dome and arches. Some idea of the appearance of Alberti's original design can be gained from viewing the side-aisle roofs of the façade of San Zaccaria in Venice by Alberti's follower Mauro Codussi.

Triumphal-Arch Form

The lower level resembles a three-portal triumphal arch.

The Basilican Façade Problem

This innovative combination of features on the façade addressed one of the problems that troubled architects throughout the Renaissance--designing an entrance façade in a classical style for a basilican church with a high nave and lower side aisles.

To unify the upper and lower stories, Alberti used a scheme of supercolumnation on the inner columns, but because the corners of the façade were lower than its center, this treatment was not repeated over the outer columns.

TRIUMPHAL-ARCH FORM

Similarity to Triumphal Arch

As highlighted by the medal, the lower story resembles a triumphal arch. The resemblance is increased by the use of dark marble around the portal, which creates a darkening that approximates the dark underside of a triumphal arch.

Symbolic Connotations

Triumphal arches have both secular and religious connotations.

Because triumphal arches functioned in Roman times to commemorate the achievements of rulers, the use of this form for Sigismondo's church implied that he, too, was a man of achievements.

In the context of Christian architecture, the triumphal arch signified the soul's triumph over death through God's gift of eternal life.

Triple-Arch Models in Rome

In using a triple-arch design, Alberti probably had in mind three-portal Roman triumphal arches such as the Arch of Septimius Severus and the Arch of Constantine.

Like these triumphal arches, the church's outer arches are smaller in both height and width, but the difference in the sizes of the central and side arches is less apparent because the side arches are elevated by platform bases, which make them nearly as high as the wider central arch.

Detailing Following Local Arch

Many of the details seem to be taken from Rimini's own ancient arch, the Arch of Augustus, rather than from the triple-arch models in Rome.

●Engaged columns. The columns are engaged rather than free-standing.

●Platform bases. The columns stand on platform bases spanning the widths of the piers instead of on their own individual pedestals.

●Absence of columnar forms under impost blocks. The areas below the impost blocks supporting the arches are not detailed as columns or pilasters, but instead, are part of the bond.

●Roundels in spandrels. Roundels rather than figural reliefs decorate the spandrels.

Composite Order Model in Rome

Alberti may have had the Arch of Titus in Rome in mind when he selected the composite order.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back