Early Christian and Byzantine Churches

BACKGROUND

Two Basic Plans

Christian churches were first built in Italy after A.D. 313, when Christianity was given the status of an official religion by the Roman emperor Constantine.

The two basic types of church plan, axial and central, were both established during the fourth century. Although these forms were modified in subsequent centuries as Christianity became established throughout Europe, the main parts were determined at this time.

The Church's western branch tended to prefer the axial plan, and its eastern branch tended to prefer the central plan.

Christian Phase of Roman History

In the Christian phase of Roman history, a number of events marked the Roman Empire's final decline, which had begun over a century before the legalization of Christianity. Early signs were instability at home and a loss of territory abroad.

●313. Constantine legalized Christianity.

●330. Constantine moved the capital from Rome to Constantinople.

● 395. The Roman Empire was divided into separate eastern and western empires, the Byzantine and the Roman Empires. (The splitting of the Church into the Roman Catholic Church in the west and the Eastern Orthodox Church in the east did not take place until the eleventh century.)

●402. Honorius, Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, moved the capital to Ravenna.

●410. The Visigoths conquered Rome.

●476. The Visigoths conquered Ravenna.

EARLY CHRISTIAN BASILICAS

Selection of Basilica Form

Once Christianity had become legal, the Church was free to develop architectural forms that were appropriate to Christian rituals. The basilica form, which was used in Roman society as a court of law and public meeting place, was selected because it could accommodate many people and provide good illumination.

Roman temples would have been unsuitable because their interiors were dark and too small for crowds, being intended to only accommodate priests and other officials. Their association with pagan rituals also made Roman temples unacceptable.

Main Parts of Roman Basilicas

●Nave flanked by side isles. The Roman basilica was rectangular in shape and divided lengthwise into a central nave and flanking side isles. The roof over the side-isles was usually lower than the nave roof, creating a vertical wall between the two floor levels that could be pierced by clerestory windows.

●Entrances. The number and positions of entrances varied.

●Apses. Apses, semicircular recesses with half-hemispherical vaults, accommodated the magistrates who presided over Roman courts. The position of apses varied, but were usually located on the ends.

Christian Modifications to the Basilica

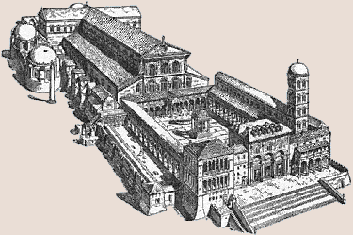

The Roman basilica plan was modified in several respects soon after it was adopted as a Christian building. These modifications are illustrated by reconstructions of Old St. Peter's.

●Atrium. A courtyard called an atrium was added to the entrance end.

●Narthex. A rectangular entrance vestibule called the narthex was placed perpendicular to the nave. Originally, the narthex was an open arcade forming the side of the atrium next to the nave, and after these forecourts ceased to be built, the narthex's outer side was enclosed.

●Nave. The nave's longitudinal space was used by worshippers, who faced the end opposite the entrance, where the priest conducted services at the altar.

●Transept. To accommodate the crowds of worshippers who came to venerate the tomb of St. Peter, lateral wings forming a transept were added at the end opposite the entrance of Old St. Peter's. Transepts did not become a standard feature right away, and many basilicas remained essentially rectangular. The intersection of the transept and the nave is called the crossing. Because crucifixion was an ignominious form of execution that the Roman civil authorities reserved for criminals and traitors, the cross was not used as a symbol of Christianity in the Roman era, and the basilica's Latin-cross plan was not intended to be symbolic.

●Apse. A single apse was placed at the end opposite the entrance. It contained the altar and the bishop's throne, which occupied the same position as the magistrate's throne had in the apses of Roman basilicas. The plans of many early apses were straight-sided instead of semicircular.

Eastern Orientation of Apses

Christian basilicas were generally oriented so that the apse faced east.

The general rule of apses facing eastward was violated in the fourth century by Constantine, who founded a number of Rome's oldest churches. Among the churches he founded with apses facing westward were Old St. Peter's, St. Paul Outside the Walls, St. Lawrence Outside the Walls, and St. John Lateran.

One explanation for this reversal in orientation in the fourth century is that this arrangement provided that the bishop within the apse be facing east when celebrating the Mass, which he performed while facing worshippers in the nave.

EXAMPLES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN BASILICAS

Rome was the site of much church building in the fourth and fifth centuries.

♦ Old St. Peter's, Rome, begun c. 333

♦ St. Paul Outside the Walls, Rome, late 4th century

♦ Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, begun 432

EARLY CHRISTIAN CENTRALIZED structures

Classical Precedents

Centralized structures had a long history before the beginning of Christianity.

Because it has neither a beginning nor an end, the circle is identified with eternity, making it appropriate for mortuary use on a symbolic level.

●Mycenaean beehive tombs. In Greece in the second millennium BC, the Mycenaeans built circular tombs called "beehive" tombs in reference to their interior shape. These structures were constructed of large stones that were laid to form steep corbel-vaulted domes. The largest one known is the so-called Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae.

●Greek tholoi. In classical architecture, the term tholos (pl. tholoi) refers to any ancient circular structure and includes such forms as tombs, temples, and commemorative structures. The term tholoi also applies specifically to circular Greek tombs, from which circular temples were derived. The first above-ground buildings were cylindrical in form and had conical roofs. Columns supported the roof on the interior. Circular temples consisted of cylindrical cellas surrounded by circular peristyles. Another type of circular building used by the Greeks is the commemorative structure that had no mortuary context. The most famous example is the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, whose cylindrical form is comprised of Corinthian columns linked by marble slabs. Lysicrates built the monument to display his prize as the sponsor-producer, the choregos, of the winning drama at the Festival of Dionysos, which took place annually at the Theater of Dionysos in Athens. Originally, Lysicrates' prize, a bronze tripod, was displayed on the roof at the top of a Corinthian capital.

●Etruscan tumuli. In Italy in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, the Etruscans built cemeteries of tumuli, tombs that were covered by circular mounds. Etruscan mounds were generally earthen and often rose from masonry retaining walls. The underground tomb chambers were often carved out of the "living rock," stone that has been left in place after removing material to form an underground cavity. The straight-sided tomb chambers found within did not reflect their circular exteriors.

●Roman mausoleums and cenotaphs. In Italy during the final centuries of the first millennium BC and the opening centuries of the next, the Romans built circular mausoleums like those dedicated to Augustus, Caecilia Metella, and Hadrian. They also built cenotaphs, structures that commemorated a deceased person whose remains were placed elsewhere.

●Roman circular temples. Like Greek circular temples, Roman circular temples had cylindrical cellas ringed by circular peristyles. This type is illustrated by the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum in Rome and the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. The Pantheon, the most famous of all ancient Roman buildings, is also a circular temple but it is uncharacteristic due to its large size and lack of peristyle

Early Christian Centralized Structures

In Early Christian architecture, centralized structures were used for tombs, martyria, and churches, categories that overlapped each other because some churches were built as tombs or martyria.

●Tombs. Tombs like Santa Costanza, which was built for Constantia, Constantine's daughter, were built in circular form. This tomb was consecrated as a church in 1254.

●Martyria. Circular martyria, which included both tombs and cenotaphs, were built to honor well-known Christians who had been martyred for their faith. A famous church that was also a martyria is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which originally included an open-air circular enclosure that encompassed the supposed burial site of Jesus Christ. After the original structures were destroyed by the Turks, Crusaders built a large rotunda over the site.

●Churches. The church of San Lorenzo in Milan consists of a large rotunda surrounded passages of lower height.

EXAMPLES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN CENTRALIZED STRUCTURES

♦ Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

♦ Santa Costanza, Rome, c. 350

♦ San Lorenzo, Milan, c. 370

BYZANTINE CHURCHES

Background

After the division of the Roman Empire into eastern and western empires, the culture of the eastern empire, known as the Byzantine Empire, evolved separately, taking much, including its language, from Greek culture.

The sixth century is considered the first golden age of Byzantine art and architecture. In the Near East, its flowering was strong in Constantinople, and in Italy, it was strong in Ravenna and Venice.

Post-Roman Political History of Ravenna

In the fifth century, the center of Italian culture shifted from Rome to Ravenna, where a number of mortuary and ecclesiastic structures marked the highly eventful passing of the fifth and sixth centuries.

●402. The Roman emperor Honorius moved the capital of the Western Roman Empire to Ravenna to escape conquest by the Visigoths, barbarian invaders from Europe.

●410. The Visigoth king Alaric conquered Rome.

●423-450. Galla Placidia, Honorius' half-sister, maintained power after his death.

●476. The Visigoths conquered Ravenna.

●493. The Visigoth king Theodoric made Ravenna the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom.

●527-65. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian ruled during the most brilliant period of Ravenna's cultural history and commissioned two of the most imaginative centralized churches in the history of architecture.

●540. The Byzantine general Belisarius conquered Ravenna.

Byzantine Churches in Ravenna

Both basilican and centralized plans were used for Byzantine churches in Ravenna. Byzantine basilicas generally had simple exteriors that expressed their internal parts.

Byzantine central-plan churches were often organized as a series of galleries surrounding a rotunda.

Church interiors were covered by mosaics that shimmered with gold and by polished marble that displayed rich coloring and distinct veining.

Byzantine Churches in Constantinople

Justinian's most admired church is Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. This church is spectacular in its large size and revolutionary in introducing pendentives.

Another influential church Justinian built in Constantinople is the Church of the Holy Apostles, which has been destroyed. This church's plan, a Greek cross with domes in the center and on the arms, was a model for San Marco in Venice.

Byzantine Churches in Venice

A second golden age of Byzantine art and architecture occurred in the tenth through the twelfth centuries. Although the main centers of Byzantine culture at this time lay to the east of Italy in cities like Constantinople and Athens, the Byzantine style was still a major influence on the art and architecture of Venice, which carried on an active trade relationship with many Byzantine port cities.

San Marco, which was begun in 1063, is one of the most outstanding Byzantine churches from the second golden age. It combines Romanesque massiveness with a typically Byzantine Greek cross plan. The cathedral's shape is obscured from the front by the addition of an entrance vestibule.

EXAMPLES OF BYZANTINE TOMBS AND CHURCHES

♦Tomb of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, 425-c.440

♦Tomb of Theodoric, Ravenna, c. 526

♦San Vitale, Ravenna, 526-47

♦Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, 532-37

♦Sant' Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, 533-49

♦Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, begun c. 504

♦San Marco, Venice, begun 1063

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back