Domestic Architecture

BACKGROUND

Social and Economic Background

The collapse of the feudal system in much of Italy in the Middle Ages affected the history of castles and palaces in that era. As new wealth was generated through business and manufacturing and more of the population lived in cities, different architectural needs arose.

Forms of Domestic Architecture

The late-Medieval period in Italy was a time of transition from the fortified forms of the Middle Ages to the refined and increasingly stylish forms of the Renaissance.

CASTLES

Decline in Importance

The importance of castles, which served as strongholds for the land-owning nobility in the early Middle Ages, declined with the rise of locally governed comuni.

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, castles were built by powerful families who had gained control of their regions. In northern Italy this had occurred in Milan, Mantua, and Ferrara, where the Visconti, the Gonzaga, and the Este, respectively, had seized control.

Castles were not built in Tuscany during this period because its cities maintained communal governments.

Defensive Features

The architectural forms that give castles their "castellated" appearance are those designed for defense. Windows were small, and walls were high and often terminated in machicolations and crenellations.

When there were outer walls, these were also crenellated. Towers functioning as bastions rose above the outer walls at regular intervals.

Moats, essentially canals around a castle's perimeter, added a further level of security.

Vulnerability to New Weapons

By the end of the fifteenth century, the invention of gunpowder and weapons that utilized it like cannon made the relatively thin walls around castles vulnerable to attack.

Transformation of Castle Form

In the thirteenth century, the castle was transformed in shape from a sprawling complex that followed the topography to a more symmetrical and compact form that was square or rectangular. This was accomplished by reducing the size of the open space between the castle and outer walls to a size that could be enclosed within the castle's own walls.

Castles of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries typically consisted of four wings connected at the corners by towers.

Examples of Castles

♦ Castle, Assisi

♦ Castello Estense, Ferrara

♦ Castello di San Giorgio, Mantua

♦ Castello Visconteo, Pavia

♦ Castello Malatesta, Rimini

♦ Castle, Sirmione

PALACES

Increased Demand

The rise of a successful business class led to an increase in the demand for family palaces in cities and towns.

Influence of Civic Palaces

Civic palaces served as models for private palaces with respect to their block-like shapes, coarse masonry, and severe style.

Size and Shape of Medieval Palaces

Because city walls limited the land available, medieval palaces extended upward rather than outward. They were narrow and tall, usually ranging from three to six stories. Courtyards were especially small.

Increased Size in the Fourteenth Century

In the fourteenth century, palaces were made wider and larger in general. Wider sites were achieved by buying adjoining properties.

Larger size also meant that more members of a clan could have apartments for their families and that these apartments could be larger.

Increasing the palace's size had practical advantages with respect to the kinds of rooms and room arrangements that were possible.

As courtyards became larger, they were made more decorative.

Functions of the Different Stories

Each of the stories had a specific function.

The ground story rested on a low basement that was used for storage. Ground-story rooms on the outer facing were often rented to shopkeepers or used for the family business. Ground-story rooms without street frontage were used for storage, service areas, and stables.

The piano nobile was used for reception rooms and private quarters for the most important family members.

The third story was made up of more family apartments.

The attic, a short story between the upper story and the roof, contained the servants' quarters and storage.

Kitchens were generally located in separate buildings, but sometimes they were placed on the top story to allow smoke and heat to escape.

Palace Façades

The dual use of many palaces for residential and commercial purposes was reflected by the ground story's having a series of large arches containing doors to shops instead of a line of windows.

Windows became more uniform in design and regular in spacing, which contributed to the overall balance of the façade. Upper-story windows were generally larger and more refined.

The need for security at the street level was addressed by the use of windows that were small and overlaid by bars. The appearance of security was often suggested by masonry emphasizing prominent joints and/or rough texture.

Amenities

During the fourteenth century, palaces were made more comfortable by several improvements.

●Window glass. Although uncommon until the fifteenth century, glass was used on the finest palaces. At that time, glass had to be imported in Italy except in Venice, which was an early center of its manufacture. Before glass was used, oiled linen or cotton fabric, which admitted light while creating a barrier, was pinned over shutters. Window glass was included among a list of "vanities" (luxuries) by a Florentine friar who interpreted the city's flood in 1333 as God's punishment for the worldliness and concern with comfort and possessions exhibited by many wealthy Florentines.

●Fireplaces built into walls. Stone fireplaces that were built into the walls became common in the fourteenth century. Earlier, braziers (metal receptacles for burning fuel) provided heat for cooking food and warming living quarters. This created a smoky environment because windows and holes in the ceiling were the only means of venting the smoke.

●Private wells. Private wells were a luxury, and most palaces were dependent on communal wells.

●Wall decoration. Textile hangings like tapestries, which were extremely costly compared with murals, were desirable for both their decorative effect and their utility in minimizing drafts. Far less expensive and more common were frescoed murals. These paintings depicted textile hangings over all but the upper wall, which often included garden views as seen through fictive architecture.

Examples of Palaces

♦ Palazzo Davanzati, Florence

♦ Palazzo Tolomei, Siena

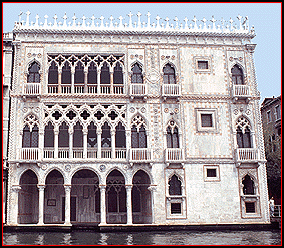

VENETIAN PALACES

Patron Families

Venetian palaces were built by wealthy merchants, who profited from Venice's being the easternmost port of Europe's Mediterranean coast. Their splendid palaces functioned both as residences for the family and as warehouses for the family business.

Among the most distinguished of Venice's patron families were the two-hundred listed in the city's Golden Book, a registry from which the doge and council members of the Venetian government had been chosen since 1297.

The palaces of the most prosperous families were located along the Grand Canal, a wide waterway that winds through a network of canals.

Palazzo Versus Ca'

As in the rest of Italy, private palaces were referred to as "Palazzo" followed by the name of the family who owned it. The designation Ca", which is an abbreviation for casa da stazio, is frequently used instead of "Palazzo" when referring to the family headquarters or palace of the family patriarch of a family whose name was attached to several palaces. Typically, as a family became larger and more prosperous, the more successful members built their own palaces.

Absence of Fortifications

Venetian palaces did not need fortifications for protection from foreign aggressors because Venetian naval forces maintained supremacy in the Adriatic Sea and much of the Mediterranean.

Consequently, palaces could be more open and include such features as large windows, loggias, galleries, and rooftop terraces. Bars on ground-story windows deterred local crime.

Site-Related Features

Venetian palaces were distinct from those of other parts of Italy because of the extreme conditions posed by the water-based site. Consequently, a number of site-related features of Venetian palaces were present during both the Middle Ages and Renaissance despite the many changes in style over the centuries.

Plan and Disposition of Rooms

Venetian palaces were designed to address two functions: providing living space for the family and warehousing goods they imported from the east to sell in Europe.

A standard arrangement of rooms that fit into the long and deep sites evolved in the Middle Ages and persisted for centuries.

A wide portico on the waterfront served as both a loading dock and formal entrance into the palace.

On the inside, a wide hallway containing a large staircase leads from the waterfront entrance to the courtyard. The land entrance is through the courtyard. This story, which was too damp to be used for living quarters, was used for warehouse space for the family business. Warehouse storage areas lay on each side of the hall.

On the second and third stories, salones occupied much of the area above the ground-story hall. In order to provide enough illumination to light the whole room, which extended far back into the palace's interior, windows were clustered across the whole front wall.

Apartments occupied the rooms along the sides.

Stylistic Influences

The principal stylistic influences on Venetian-palace façades before the Renaissance were the Byzantine and Gothic styles, which were evident in a variety of arch types.

●Byzantine Style. The most characteristic feature of Byzantine-influenced façades was the silted arch, which had a semicircular top and straight sides. The façade was first divided into three parts at the end of the Byzantine phase of the development Venetian palaces.

●Gothic Style. In the Italian-Gothic phase of the development of Venetian palaces, tracery and Gothic arches, especially ogee (S-curved) and tri-lobe arches, were used. After the building of an elaborate tracery-topped arcade at the Doge's Palace toward the end of the fourteenth century, many private palaces adopted this florid style of Venetian-Gothic design, which reached its peak in the fifteenth century.

Examples of Venetian Palaces

♦ Palazzo degli Ambasciatore, Venice

♦ Palazzo Contarini-Fasan, Venice

♦ Casa Goldoni, Venice

♦ Ca' Loredan, Venice

♦ Palazzo da Mula, Murano

♦ Ca' d'Oro, Venice

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back