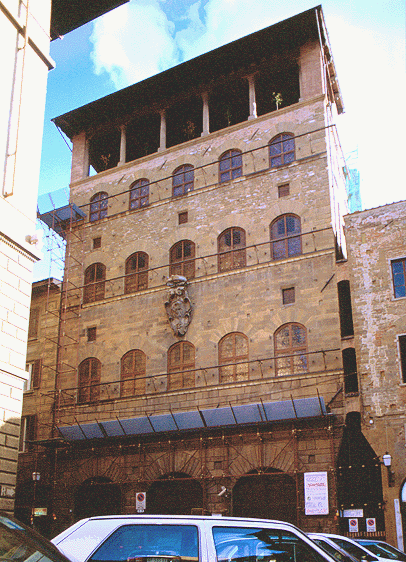

Palazzo Davanzati

Florence, c. 1330

BACKGROUND

Ownership and Uses of the Palace

Although the Palazzo Davanzati functioned as the residence of a wealthy family for around six centuries, its recent history has included other uses.

●c. 1330: Davizzi family residence. The Davizzi family, a rich family who made their fortune in the wool trade, built the Palazzi Davizzi around 1330. Although the palace was primarily a residence, from 1427 until the completion of the Uffizi Palace, which was built to amalgamate all of the city's government offices, part of the Palazzo Davanzati was used as a tax office. Because possessions were taxed, the records found there reveal much about commissions for art and architecture.

●1516: Bartolini family residence. When the Davizzi family's financial circumstances declined and they could no longer maintain such a palace, it was sold to the Bartolini family.

●1578: Davanzati family residence. The Davanzati family purchased the palace in 1578 and made improvements such as adding a rooftop loggia.

●1838: Tenements. After the death of the last member of the Davanzati family in 1838, the palace was divided into tenements and allowed to deteriorate.

●1904: Private restored house museum. In 1904, the palace was purchased by Elia Volpi, an antiquarian and painter, who restored and opened it as a private museum in 1910.

●1951: State-owned house museum. The Italian state acquired the property in 1951 and uses it as a museum, the Museo della Casa Fiorentina (Museum of the Florentine House), to display items related to early Florentine domestic life.

Restoration by Elia Volpi

Elia Volpi's restoration from1905 to 1910 included the removal of many coats of whitewash. In many chambers, this revealed the original fourteenth century fresco decoration, which illusionistically depicts architecture, wall hangings, and scenes beyond fictive openings. Doors, windows, and much of the woodwork were replaced using old materials. The terra-cotta floors were also replaced.

Current Furnishings

The original furniture is long lost, and the furniture shown in the black-and-white photographs of the interiors was acquired by Volpi after World War I. Although some of these pieces remain, most of the current furnishings were donated by other museums and private donors.

INFLUENTIAL FEATURES OF FAÇADE

Principles and Influence in Next Century

The façade shows a greater concern for regularity and symmetry, qualities that were stressed during the Renaissance. The façade creates an overwhelming impression of regularity despite such irregularities as the asymmetrical projection of the upper stories on one side and the lack of continuity between the five windows of the upper stories and the three arches of the ground story.

The following features of the Palazzo Davanzati's façade were repeated in the next century on the highly influential Palazzo Medici.

Lack of Ornamentation

Although the use of ornamental moldings and other carved features was typical in the fourteenth century, there was no ornamentation other than the texture of the masonry. (The highly decorative family crest was not added until the sixteenth century.) The severity resulting from the lack of ornamental features further emphasizes the façade's regularity by clarifying the main features.

Arches on the Ground Story

The ground story differs from the other stories in having three large arches, which were hung with large wooden doors that could be closed at night.

Ground story rooms facing the street were useful for conducting business or renting to shopkeepers.

Stringcouses Marking Story Divisions

String courses below the rows of windows mark the divisions between the stories. Their use clarifies the design and adds horizontal accents that counterbalance the palace's vertical shape.

Regularly Spaced, Matching Windows

The windows are uniform in shape and spacing along each row. They are also aligned vertically from row to row.

The small rectangular windows of the ground story, which were placed high and covered with iron bars to make them secure, are centered above the arches.

The windows of the second and third stories are the same size, and those of the fourth story are smaller.

Although the windows have segmental arches, which were less favored in the Renaissance than round arches, the consistent use of them to span all the openings is consistent with the Renaissance principle of regularity. In having longer voussoirs at the top, these arches are similar to Florentine arches, whose openings are round.

Diminishing Heights of Stories

The heights of the original four stories decrease as the stories rise.

Changes in Masonry Texture

The different stories are distinguished by changes in the texture and refinement of the masonry. The stones are dressed and laid with prominent joints at the street level, partially dressed and laid without prominent joints at the second level, and less carefully finished on the upper levels, where the infill is coarser. The infill on the third story is composed of rough-surfaced stones, and that of the fourth story is of brick.

PLAN AND GENERAL DESIGN

Site

The Palazzo Davanzati stands on a large, block-deep site that was formerly occupied by the residences of several members of the Davizzi family. Tower-like palaces are believed to have occupied the northern and southeastern sections of the palace, which face two different streets.

Both the expenses and the spaces of the new palace were shared by several Davizzi households.

Influence from Civic Palaces

The Palazzo Davanzati's severe styling, blockish shape, and central courtyard echo similar features found on late-Medieval civic palaces like the Bargello and the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Its similarity to fortified civic palaces would have been greater before the addition of the rooftop loggia in the sixteenth century because crenellations, another characteristic of civic palaces, probably capped the roof edge originally.

Private Courtyard

Because the site was an amalgamation of several properties that were clustered around a common courtyard, the Palazzo Davanzati's courtyard was private. In the fourteenth century, most palace courtyards were shared with neighbors.

The courtyard was supported by a combination of free-standing and engaged octagonal pillars. The capitals vary in design, and one of them is carved with portrait heads of members of the Davizzi family.

The vaulted areas around the open well were used for storage, servants' quarters, and stables.

A spacious staircase snakes around the outer wall and connects the corbel-supported galleries that ring each story. The galleries serve as hallways connecting the rooms on each level.

Rooms

The same plan governs the second, third, and fourth stories, dividing each floor into five rooms. The head of the family would have occupied the piano nobile.

DECORATION OF THE INTERIOR

Illusionistic Frescoes

The walls of most of the rooms were decorated by trompe l'oeil frescoes illustrating features such as carved cornices, expensive wall coverings, and views through fictive openings.

Wooden Ceilings

Ceilings were constructed of timber beams. Large, elaborately formed and carved corbels add to the richness of the woodwork. Many of the surfaces were ornamented by painted patterns, which were frequently applied by stenciling.

Terracotta Floors

Floors were made of terracotta that was rubbed with oil. The patterns varied from room to room.

Significant Rooms

The largest of the Palazzo Davanzati's rooms are the saloni on the front facing, which measure 23' deep and 53' long. These rooms would have been used for entertaining and group activities like meals. The large room on the rear of the palace would have been the principal bedchamber. Because the piano nobile was the domain of the head of the family, many of the most lavishly decorated rooms are located on that story.

●Salone on Piano Nobile. The salone on the piano nobile is 20' high. There is evidence that this room was divided some time after it was decorated. The smooth plaster walls are mottled in warm neutral colors. Stenciled patterns decorate the timber-frame ceiling, and carved bolsters (corbels) brace and accentuate the main beams. A large fireplace of pietra serena is built into the wall so that the smoke is carried out through the walls. The five large windows have circular leaded panes and wooden shudders, which can both be opened to the inside of the room when fresh air is wanted.

●Room of the Parrots. The large room on the piano nobile that faces the alleyway is known as the Sala dei Papagalli, the Room of the Parrots. It is named for a frescoed parrot motif in the light-colored diagonal bands framing diamond-shape panels. The whole was intended to resemble a patchwork wall covering.

●Room of the Peacocks. The large room on the southeastern facing of the piano nobile, which was used as a bedroom, is called the Sala dei Pavoni, Room of the Peacocks. Peacocks and other exotic birds can be found in the part of the upper wall that is painted to resemble a series of trees and shields beneath a row of gables. Much of the wall is painted with a geometric pattern in which interlacing Ds, which refer to the Davizzi name, form compartments containing crowns, lions, and fleurs-du-lis.

●Davizzi-Alberti Nuptial Chamber. The large southeastern room on the third story is the Davizzi-Alberti nuptial chamber. Crests of the two families were incorporated in the fresco decoration of the walls and ceiling. A frescoed frieze around the upper wall illustrates a story from the courtly love tradition of medieval France.

AMENITIES

Well and Pulleys in Walls

The Palazzo Davanzati had not only its own well but also a means of bringing water to the upper floors. Systems of pulleys built into the walls at the palace's corners brought water to the major rooms on all stories.

Fireplaces Built into Walls

The main rooms contain fireplaces that were built into the walls or corners. Before fireplaces were built-in, open fires in braziers were used for heat, which created smoke that was difficult to remove through windows.

Leaded-Glass Windows

The windows contained glass panes set in leading. Glass was a luxury feature at this time, and the lights of windows were commonly made of oiled linen.

The panes and leading of the second and third stories are circular, and those of the fourth story are diamond-shaped.

Wrought-Iron Hardware

In addition to such standard items of exterior palace hardware as hinges, door bolts, door knockers, hitching rings, and torch holders, the Palazzo Davanzati had fittings for hanging luxuries such as awnings and wall hangings.

●Hooks and brackets for hanging awnings. Awnings were useful because they blocked the sunlight while allowing air to circulate. The tops of the awnings were suspended from wooden poles held by wrought-iron hooks above the windows. The bottoms of the awnings were held about three feet out from the building by poles that were held by brackets.

●Hooks for hanging wall coverings. Wrought-iron hooks that were spaced about a foot apart were installed along the string courses for use in hanging tapestries or other special wall coverings during times of celebration.

Loggia on the Rooftop

The addition of a loggia to the rooftop in the late sixteenth century provided the residents with a pleasant spot from which to enjoy the open air and a view of the city. Much of the view is now blocked by the addition of a building across the street, the Via Porta Rossa.

The loggia not only provided a space for leisure but also modernized the façade by replacing the crenellations, which were outmoded by the fifteenth century, with a horizontal feature.

Palazzo Davanzatti, Florence

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back