Villa Medici

Poggio a Caiano, begun 1485

Architect: Giuliano da Sangallo

BACKGROUND

Name

Poggio means "hill" in Italian, and as suggested, the Villa Medici is located in a hilly region.

Competition for the Commission

In the early 1480s Lorenzo de' Medici held a competition for the design of a villa that would be built at Poggio a Caiano, a few miles west of Florence. The design by Giuliano da Sangallo was selected over those of many more experienced architects, including Giuliano's own master, Francione.

Lorenzo's Influence

Lorenzo was one of the most astute and design-oriented patrons of architecture in the Renaissance. From letters and other documents, it is clear that he contributed much to the design of the villa at Poggio a Caiano.

Lorenzo's ideas would have been affected by his knowledge of architectural treatises, which he would have shared with Giuliano. His knowledge of Latin would have enabled him to read Vitruvius before the publication of translations.

Lorenzo was also familiar with Alberti's treatise. He read the individual chapters as soon as they were printed.

Another source of architectural theory that Lorenzo knew was Filarete's treatise. Although it was not published until recently, Lorenzo knew this work because the author had sent a copy of the manuscript to his father, Piero the Gouty, in hopes that he would be inspired to commission the sort of architectural schemes he described.

Significance

In being much larger and more ostentatious than earlier villas, the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano marks a transition point in villa design. Its increased size accommodated large-scale entertaining.

CONSTRUCTION HISTORY

Overview

The history of the Villa Medici's sporadic construction and decoration was largely precipitated by the changing circumstances of Medici power. During the period of the villa's construction and decoration, the family twice experienced exile from Florence and twice saw a member elected pope.

1474: Purchase of property. In 1474 Lorenzo purchased the property from Giovanni Rucellai, who had bought it from his father-in-law, Palla Strozzi.

1485: Beginning of construction. Construction was begun in 1485.

1494: Cessation of construction. Construction ceased in 1494 when the Medici were expelled from Florence after the French invasion of Italy. Only the front third of the villa had been completed, and the salon was not yet vaulted.

1512: Medici regain power. With the help of Julius II, the Medici regained control of Florence in 1512, and Giovanni de' Medici became Pope Leo X the following year.

1515-19: Completion of structure. Construction resumed in 1515, and the villa was completed according to Giuliano's design in 1519.

1520: Beginning of decoration. The fresco cycle decorating the salone was begun by Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio, and Jacopo Pontormo following a program by Paolo Giovio.

1521: Cessation of decoration. Pope Leo X died in 1521, and decoration ceased.

1531-34: Continuing of painting. In 1531, Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici) re-commissioned the painting of the salone to Pontormo, but little was completed before the pope's death in 1534.

1578-82: Completion of decoration. In 1578, Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici commissioned Alessandro Allori to finish the salone frescoes according to a revised program by Vincenzo Borghini.

MAIN PARTS

Square, Compact Block

The villa is structured as a square block capped by wide eaves and belted on the ground story by a loggia. When seen from the front, the building has a cubic quality that is enhanced by the absence of string courses and the presence of quoins on the corners. The block's severity is emphasized by the contrast between the unadorned, cream-colored plaster of the wall surface and the dark pietra serena of the trim.

When seen from the sides, however, indentations change the shape of the upper storie from a square to an H-shape. The indentations allow light to reach the ends of the salone at the building's core.

Belt of Ground-Story Loggias

A continuous ground-story loggia surrounds the central block on all four sides. The arches and piers forming the loggia are constructed of red brick, which makes the loggia distinct from the main block.

A balustrade on the loggia's roof edge identifies the terrace formed by the loggia's roof.

Wide Eaves

Visually, the wide eaves function to cap off the villa's cubic mass, and functionally, they provide shade and shelter to the terrace around the perimeter on the piano nobile.

Temple Front Screening Recessed Portico

A classical temple front consisting of columns carrying a pediment screens the opening of a recessed portico. This is the first example of a temple-front façade in Italian Renaissance domestic architecture.

Because the entrance portico is recessed, the temple front consists of decorative moldings and relief applied to the wall plane rather than a porch with a pitched roof that projected out from the main structure.

The height-to-width proportions of the temple front of the Villa Medici are squat compared with those of most temples. The presence of the central windows on the top story made it impossible to place the pediment higher.

The use of a barrel vault for the ceiling of a classical portico has no precedent in ancient architecture.

Later Additions

Several features were added after the Renaissance such as a clock set in a large crest on the roof and curving staircases that replaced the horse ramps, which ran perpendicular to the façade.

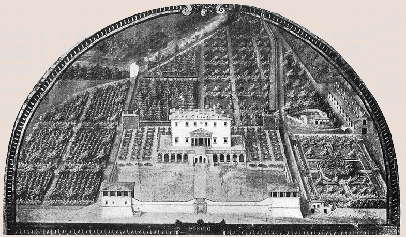

A painting of the villa executed near the end of the sixteenth century illustrates its pre-Baroque form.

INNOVATIVE FEATURES

Temple-Front Entrance

This is the first use of a Classical temple front on a villa (or palace). Temple-front porticos of the colossal order later became a hallmark of Andrea Palladio's villas.

Symmetrical Plan

The plan is symmetrical in its outer shape and nearly symmetrical in the arrangement of rooms on the interior.

Because apartments occupy the corners on the piano nobile, the public spaces, including the open terraces, form a Greek cross within a square. The center is occupied by a large rectangular salone.

Enfilade Openings

The interior doorways are aligned on axes so that when the doors are open, a series of rooms can be seen. This arrangement, called enfilade doorways, was used at many grand palaces. Enfilade openings were used at the Vatican Palace on the wing begun by Nicholas V (1447-55), whose piano nobile is known as the Raphael Stanze.

Large, Barrel-Vaulted Salone

The salone is revolutionary in its large size and use of a coffered barrel-vaulted ceiling. Giuliano's studies of ancient sites probably inspired the latter feature.

ROMAN-INSPIRED DECORATION

Relief Sculpture on Portico

Classical forms like the pediment and frieze were ornamented with relief sculpture as they had been in ancient times, but the subject matter was personalized to reflect the Medici family.

●Pediment. In the center of the pediment is a relief of the Medici-family crest. Extending from it on each side are two ribbons following a serpentine course that fills the pediment's acute angles.

●Frieze. The blue and white terracotta frieze of the entablature is classically inspired in form and content. It is an allegory of Time and includes a number of ancient agricultural deities including Janus. As the god of January, Janus refers to Lorenzo de' Medici's January first birthday. Janus is also the god of all beginnings, and alludes to the Return of Time and the Golden Age of the Medici under Lorenzo.

Fresco Decoration of the Salone

Fresco, a medium that had also been used by the Romans in its a secco mode, was used to decorate the salone. Scenes of Roman history and mythology are filled with allegorical meanings that promote and glorify the Medici dynasty.

●Artists. The fresco paintings were begun by Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio, and Jacopo Pontormo around 1520-21. They were finally completed between 1578 and 1582 by Alessandro Allori according to a revised program by Vincenzo Borghini.

● Subjects. It is thought that the figures in the lunette of the salone depicts the story of Vertumnus and Pomona from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The two gods are surrounded by other agricultural deities, and an inscription above their heads, taken from Virgil’s Georgics, refers to the divine nature of agriculture. Some scholars believe the figure of Vertumnus represents Janus, and thus Winter, Pomona is Spring, and the fresco can therefore be interpreted as the Four Seasons.

Scenes illustrating Roman history parallel the Medici family's own history. For example, an event of 1487, during which Lorenzo the Magnificent was presented with exotic animals by the Egyptian ambassador, is represented in Andrea del Sarto’s Caesar Receiving Tribute, in which Caesar is presented with gifts from a sultan. Lorenzo is depicted as Caesar and is thus made analogous to the ancient Roman ruler. Such a portrayal was typically associated with rulers of noble origins and would have been considered boastful and inappropriate by Florentines, who recalled the Medici's commercial roots and resented the family's role in ending Florence's self-government.

Coffering of Barrel Vaults

The interlocking of curved terracotta tiles for coffering, which was used for the barrel-vaulted ceilings of the portico and salone, emulates an ancient Roman technique of coffering. Like the pediment, these blue and white terracotta tiles also contain Medici coat-of-arms.

Grotto with Herms

Behind the loggia on the rear facing is a grotto, a type of garden feature that had been used by the Romans. Its freestanding supports are herms in the form of satyrs.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back