![]()

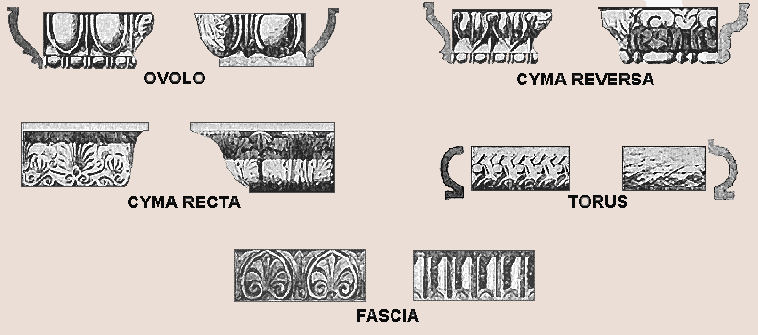

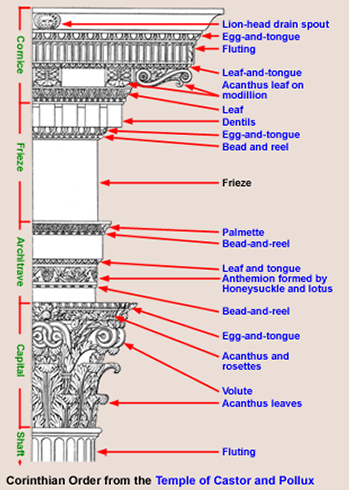

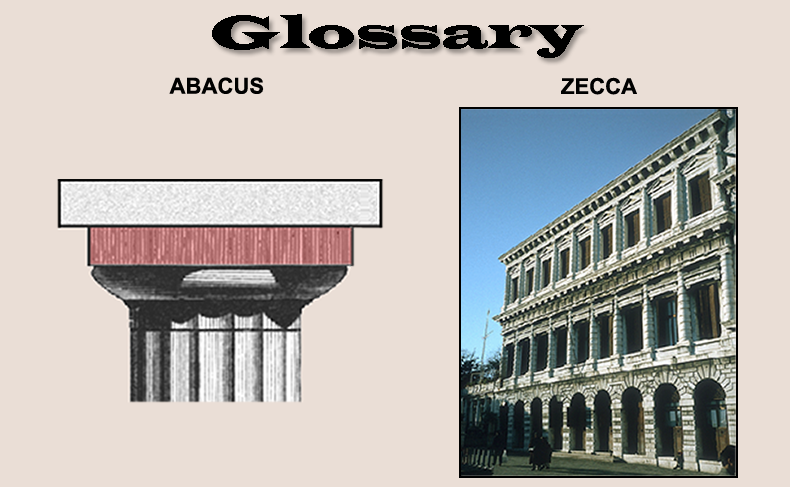

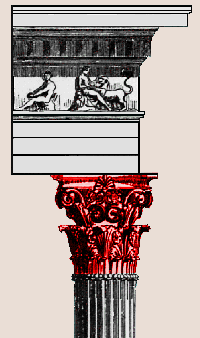

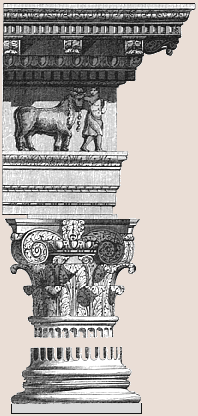

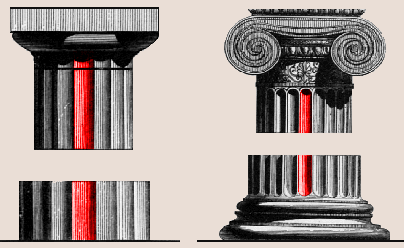

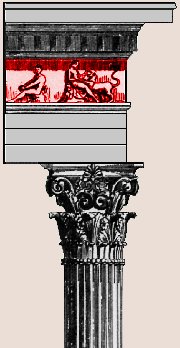

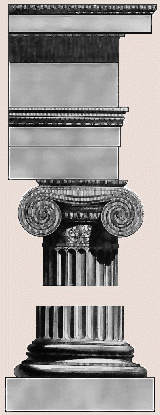

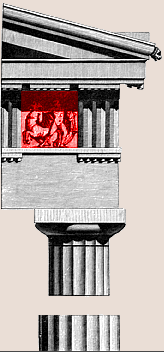

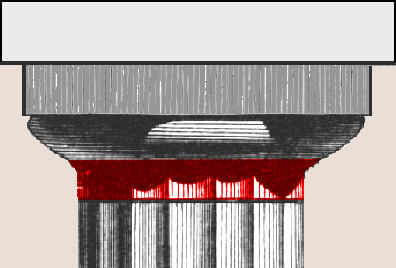

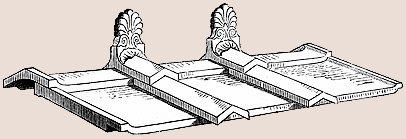

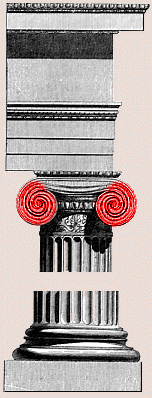

ABACUS. A flat block that forms the top part of a capital, making a transition from the round echinus below to the long, straight entablature above.

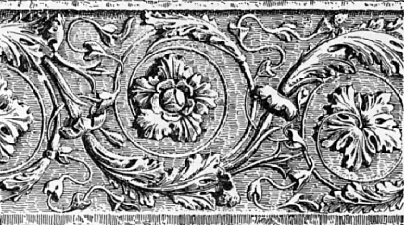

ACANTHUS LEAF. A broad plant leaf whose conventionalized form was an important motif in classical architecture where it was used on capitals, brackets, and trims.

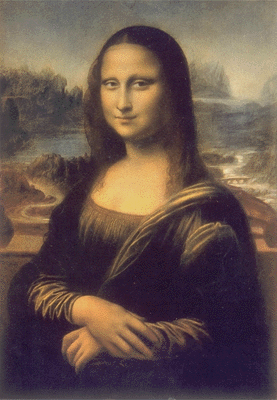

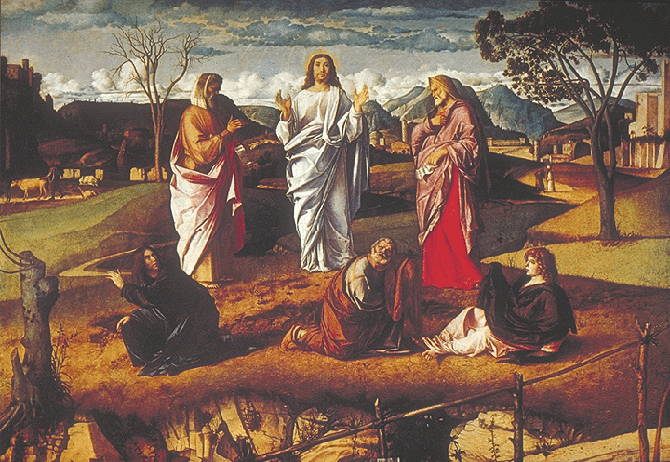

AERIAL PERSPECTIVE. The rendering of the illusion of distance on a two-dimensional surface by depicting the visible effects of the intervening volume of atmosphere:

●Blurred outlines. Outlines are blurred, and consequently, detail is limited.

●Faded color. All dimensions of color are altered--hues are bluer, values are lighter, and intensity is reduced.

Although practiced in ancient times and noted by Alberti, this technique was most thoroughly investigated by Leonardo da Vinci. It plays a role in many of his works and was one of the subjects on which he wrote extensively. It is also called "atmospheric perspective."

Massacio's The Tribute Money, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, c. 1427

The distant hills and trees show the effects of atmospheric perspective.

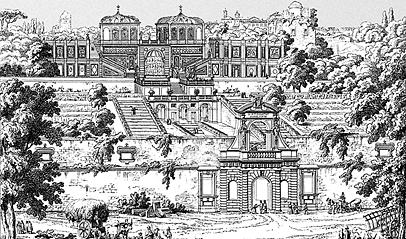

ALLÉE. Long, straight garden walkway with a surface that is suitable for pedestrian traffic such as grass or gravel. In the Renaissance they were usually defined by hedges, groves, or other landscaping features, and their terminal points were often large, well-defined features such as large statues, fountains, or obelisks. When an allée traverses sloping land that has been terraced, a series of focal points were often placed at junctures between levels or at their centers. Large gardens may have a number of allées.

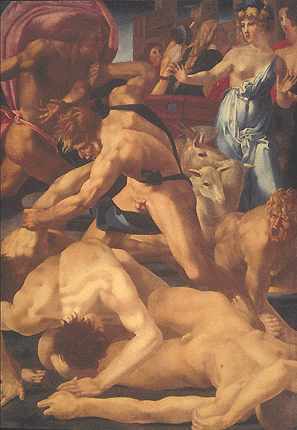

ALLEGORY. Subject in which figures, objects, etc. may symbolize or represent abstract qualities or principles like Truth and Justice, thereby giving the work a higher moral or intellectual level of meaning.

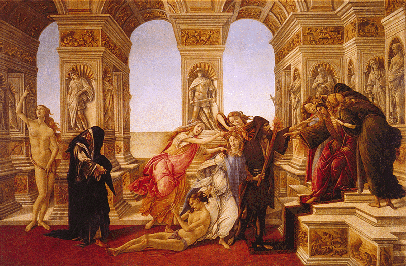

Botticelli's Calumny of Apelles, 1497-98

The subject, which was suggested by the humanist Alberti in his treatise on painting, is based on a description of a lost painting by the Greek painter Apelles. In the center, Calumny, preceded by Hatred and assisted by Fraud and Deceit, drags a youth to judgment. On the right, Midas, who is accompanied by Ignorance and Suspicion, sits in judgment. The nude on the left represents Truth, who needs no adornment, and the old woman next to her stands for Penitence. |

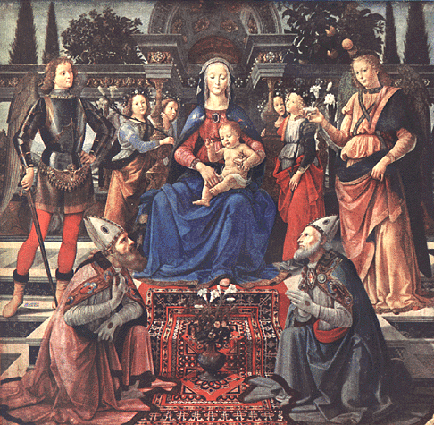

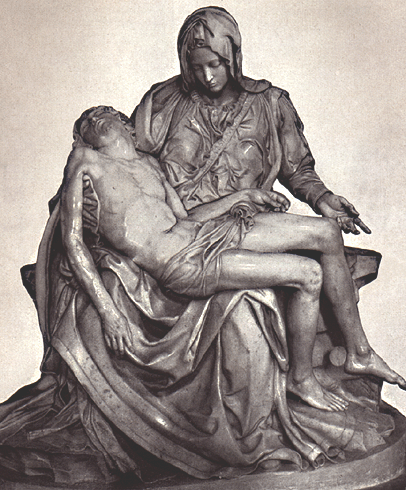

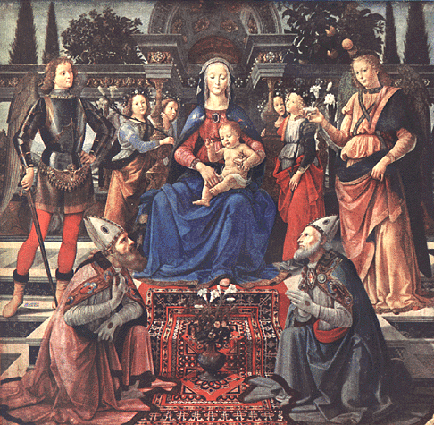

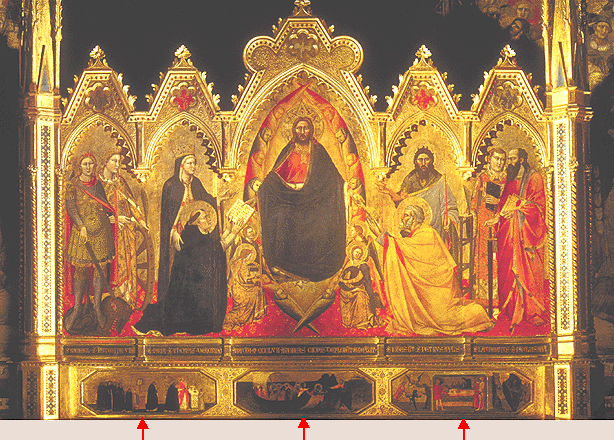

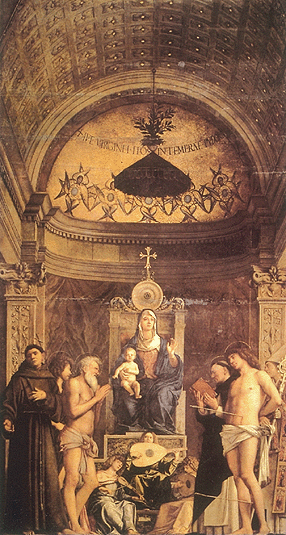

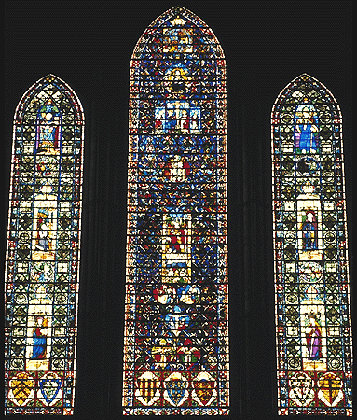

ALTARPIECE. Painted or sculpted work that is placed on, above, or at the back of an altar. Until canvas was introduced, altarpieces were often made from wooden panels that were fastened together in gilded frames. Multi-panel altarpieces such as diptychs (two panels), triptychs (three panels), and polyptychs (several panels) were often used for Medieval altarpieces.

Pinturicchio's Aeneas Receives the Cardinal's Hat from Pope Callistus III, 1456,

Piccolomini Library, Siena Cathedral, 1503-8

(altarpiece in center)

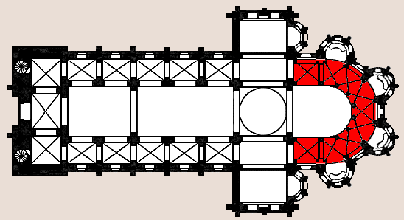

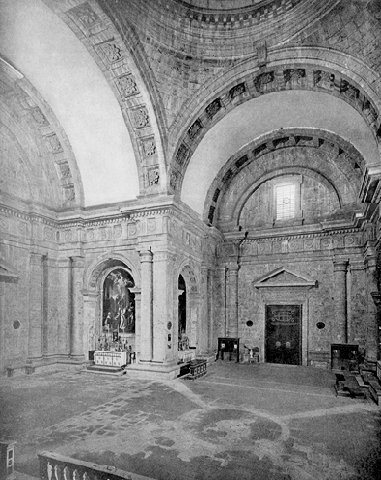

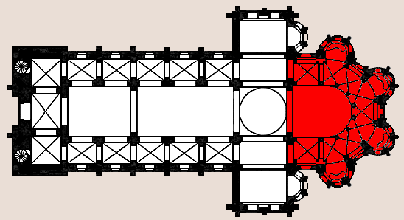

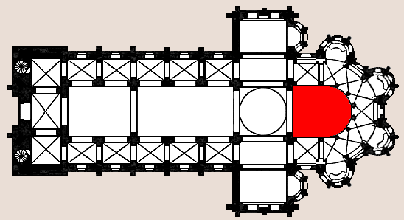

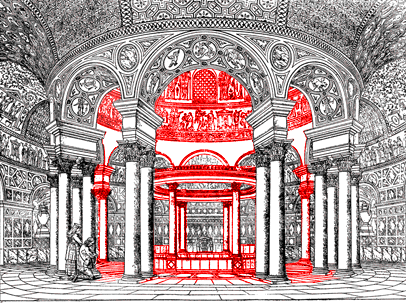

AMBULATORY. Circular or polygonal aisle that encircles the apse of a basilican church or the rotunda of a central-plan church. It provides a passageway connecting the two side aisles, which was useful for ceremonial processions and enabling visitors to tour the perimeter of a church without disturbing the services. This benefit was especially important in churches whose sacred relics attracted a stream of pilgrims.

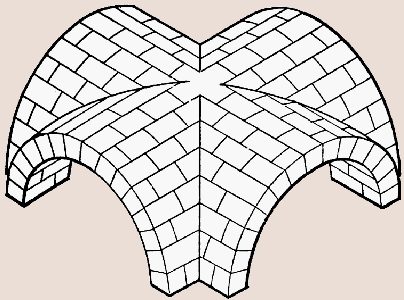

ANNULAR VAULT. Ring-shaped tunnel vault.

Santa Costanza, Rome, c. 350

|

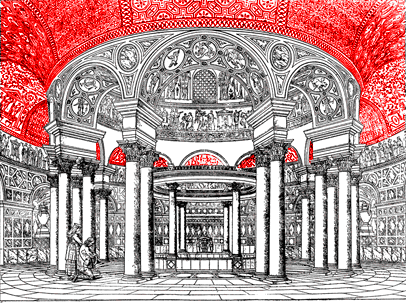

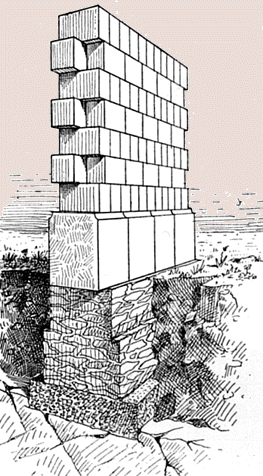

AQUEDUCT. Bridge-like structure containing a channel for carrying water from mountain springs to cities or villas. Aqueducts were first built by the Romans, who often used concrete to expedite the construction of these long arcaded structures.

Pont du Garde, Nîmes, France, late 1st century BC

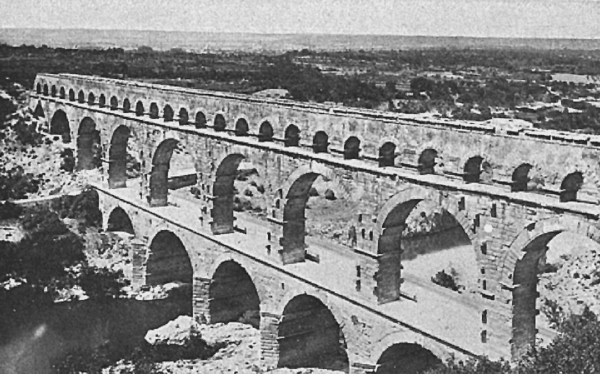

ARABESQUE. Fanciful decoration in which spiraling and free-curving lines are integrated with plant forms, especially vines, foliage, and flowers.

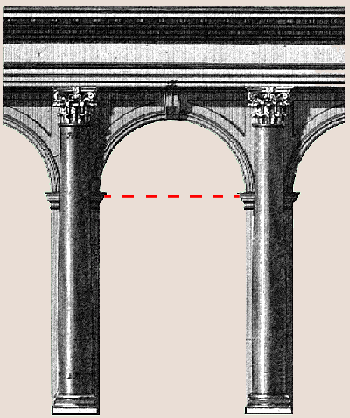

ARCADE. A continuous series of side-by-side arches. Constructing arches in a line solves the problem of bracing their outward thrust because the arches push against each other. In the Renaissance, arcades were often used to carry the open side(s) of loggias and to support ceilings/roofs when division without separation was desired such as nave arcades.

Aqueduct, Tunisia

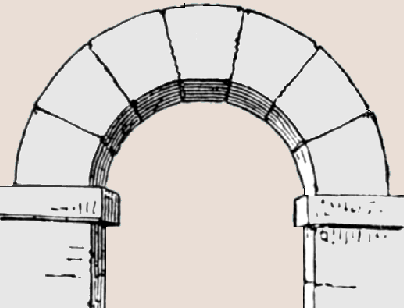

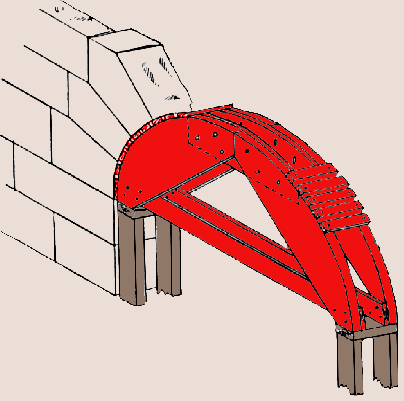

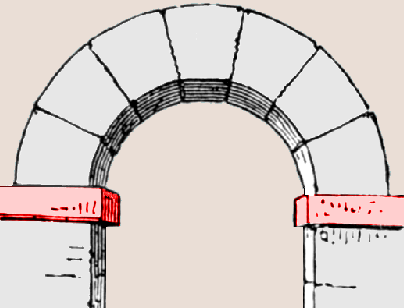

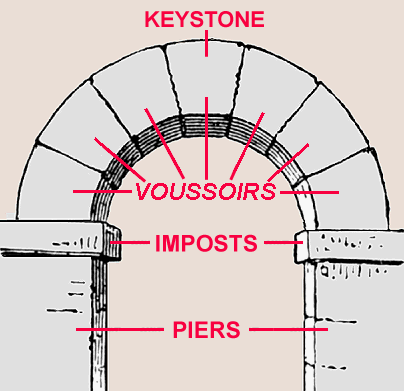

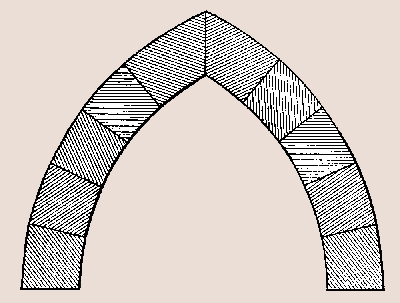

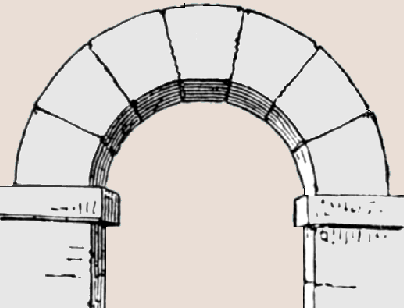

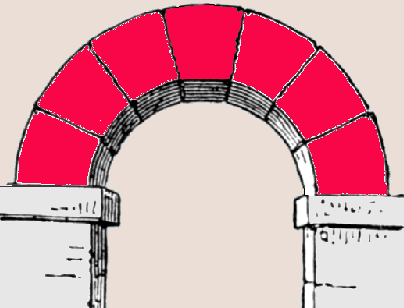

ARCH. Structure composed of wedge-shaped blocks, called voussoirs, which are typically laid along a curved framework called centering. After the final stone, called the keystone, is placed in the center, the pieces hold each other in place, and the centering can be removed. Arcuated construction allows for wider spans than are possible using beams, whose lengths are limited by their tensile strength (resistance to breaking under tension). The arch transfers much of the structure's downward thrust outward, and bracing by buttresses or adjacent arches is necessary. The openings formed by arches vary in shape. In Roman and Renaissance architecture, semicircular arches, also called a round arches, were used, whereas in Gothic architecture, a steeper arch with a pointed apex was favored. The Florentine arch is a form of semicircular arch whose voussoirs are longer towards the center. An arch based on an arc of less than 180 degrees is segmental. Although it is less supportive, arches can also be flat because the critical feature of an arch is the wedge shape of the pieces, not the shape of the opening. See corbel arch, a "false arch" developed earlier.

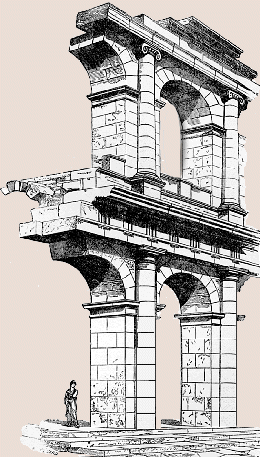

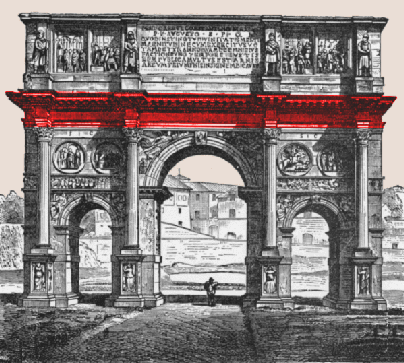

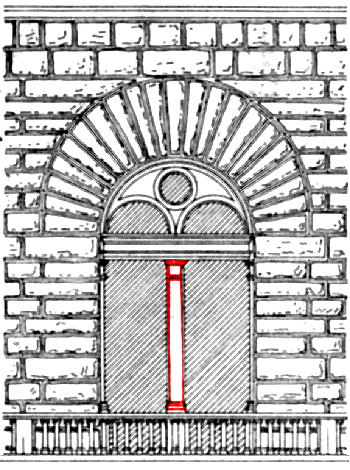

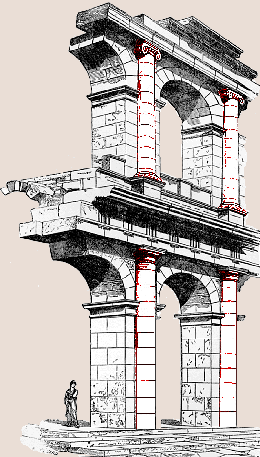

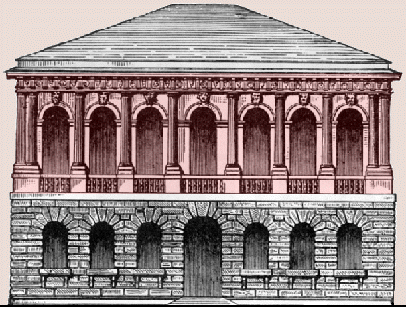

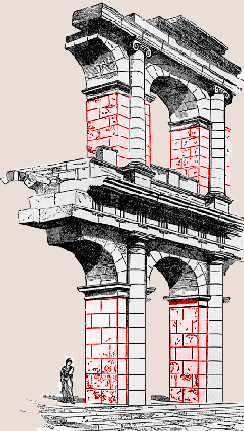

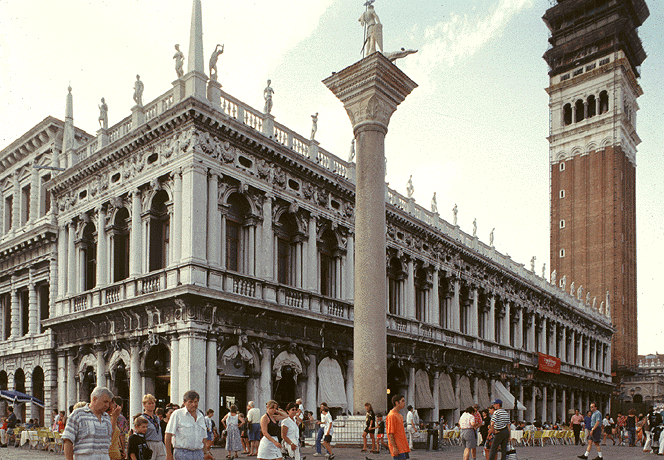

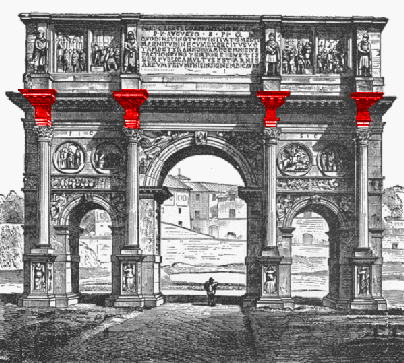

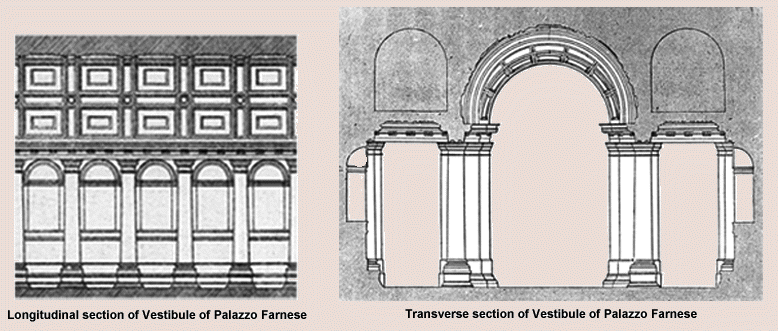

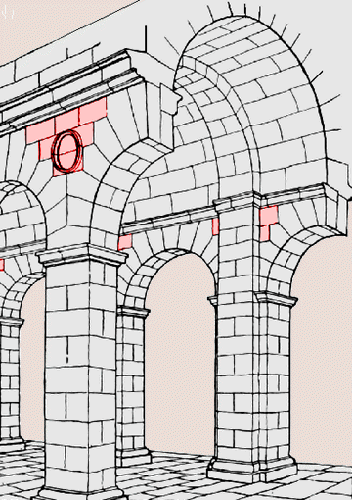

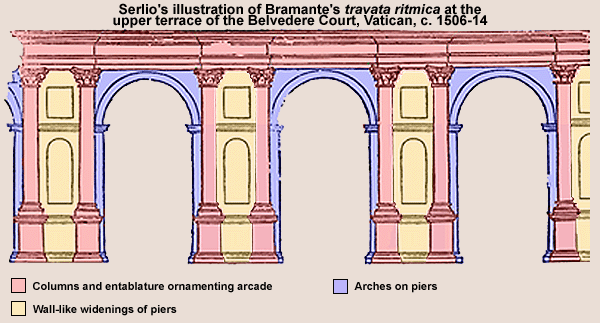

ARCH ORDER. Combination of architectural elements invented by the Romans in which piers and arches are ornamented by columns and entablatures. This form was widely used in the Renaissance, as it had been in Roman times.

Detail of Theater of Marcellus, Rome, 23-13 BC

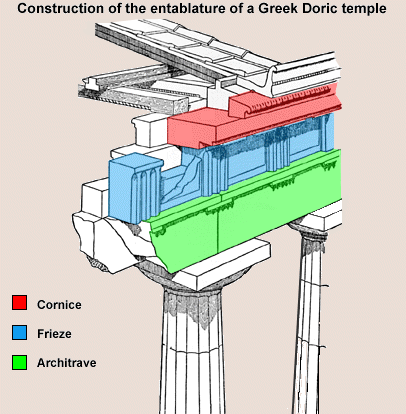

ARCHITRAVE. A form of lintel that spans the columns and forms the upper of the three horizontal members of the entablature. The spacing of the columns is limited by the tensile strength (resistance to breaking under tension) of the beams forming the architrave.

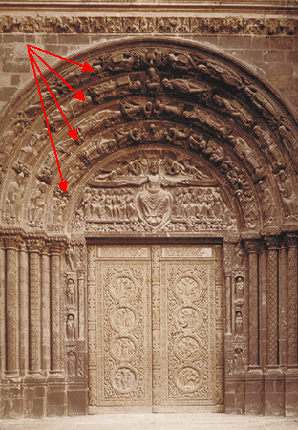

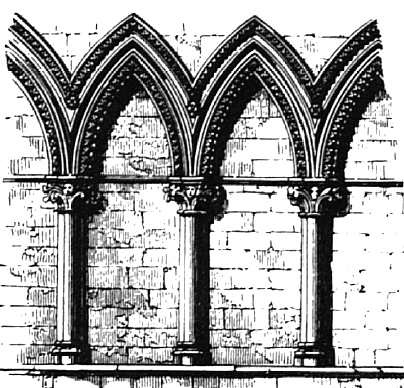

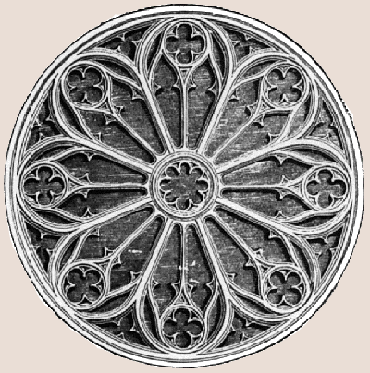

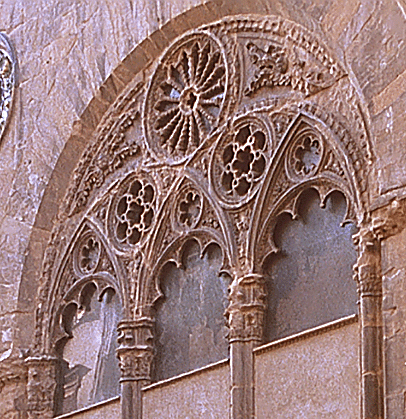

ARCHIVOLT. A molding on the outer face of an arch. On the portals of Romanesque and Gothic churches, a prominent series of archivolts spring from corresponding members of jambs and surround a tympanum.

St. Denis, Paris, 1140

ARCUATED. Constructed according to the principle of the arch.

Antonio da Sangallo the Elder's Church of Madonna di S. Biagio, Montepulciano, begun 1518

ARRICCIO. Rough plaster layer that is applied to the wall to be frescoed before the application of the smooth layer of intonaco.

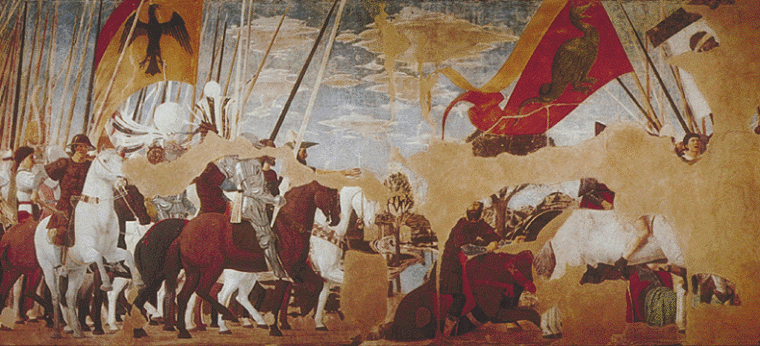

Piero della Francesca's Battle of Constantine and Maxentius, 1454

The arriccio can be seen in areas where the fresco-covered intonaco layer has come off.

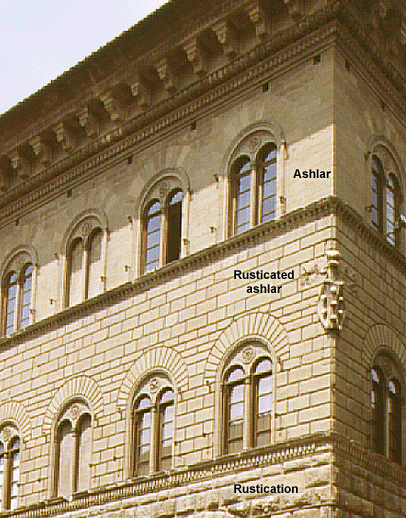

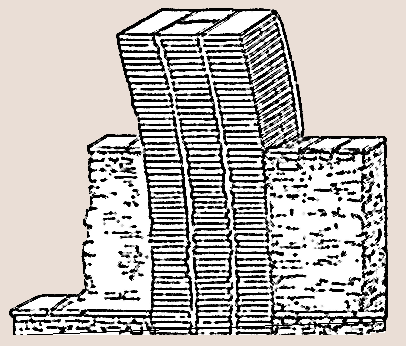

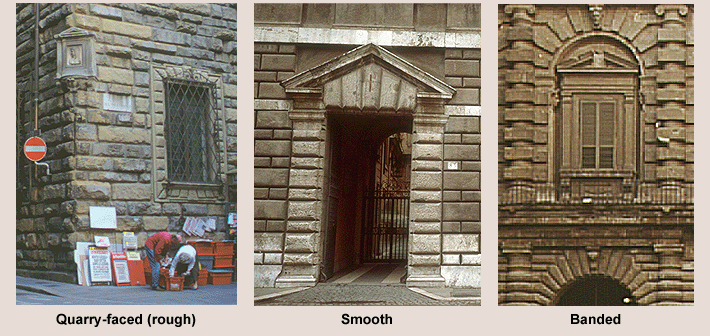

ASHLAR. Masonry in which square-cut rectangular blocks with smooth faces are laid with small or imperceptible joints. A textured form of ashlar called rusticated ashlar results from combining the deep joints of rustication with the smooth faces of ashlar. Bastard ashlar refers to masonry using thin slabs instead of blocks. Blocks that are smoothly finished on the outer facings are often referred to as dressed stone.

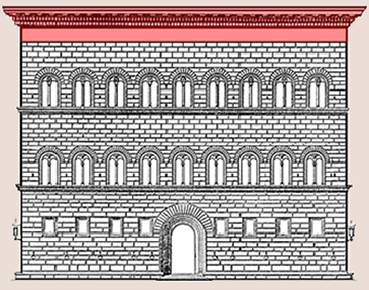

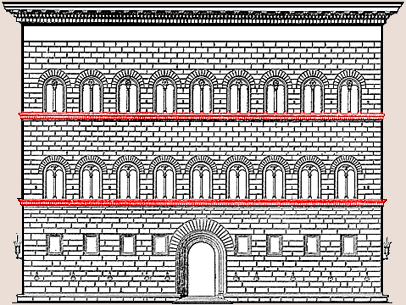

Michelozzi's Palazzo Medici, Florence, begun 1444

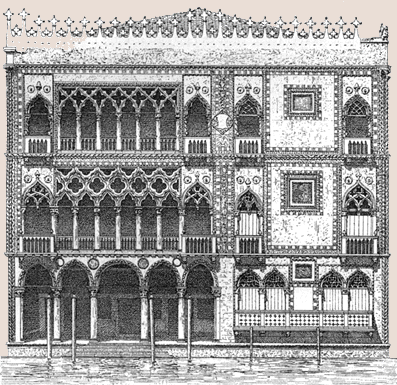

ASYMMETRY. Arrangement in which the forms on one side of the center do not mirror those on the other. Lack of symmetry does not necessarily mean lack of balance; for instance, in compositions having informal balance, a large form on the right might be balanced by several small forms on the left.

Ca' d'Oro, Venice, 1421-37

ATMOSPHERIC PERSPECTIVE. See Aerial Perspective.

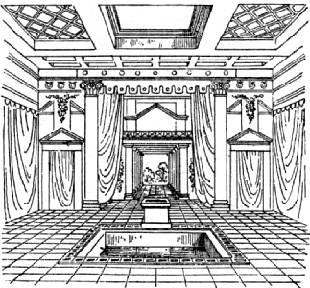

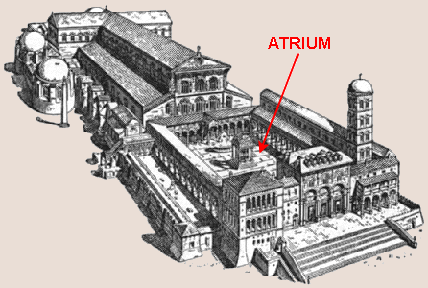

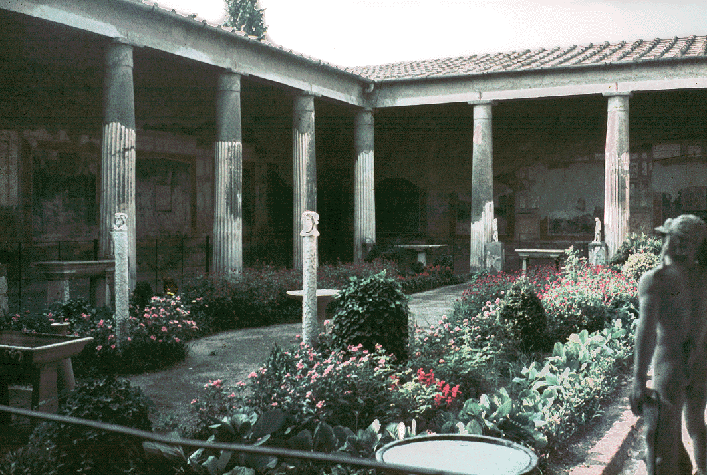

ATRIUM. Open court at the entrance of a Roman domus (house) or Early Christian church. The atrium of a domus had a pool for catching rainwater, and that of an early Christian church had a font (basin) for baptism, which at that time, involved immersion.

Reconstruction of Atrium of a Roman domus |

Reconstruction of Old St. Peter's, c. 324-30 |

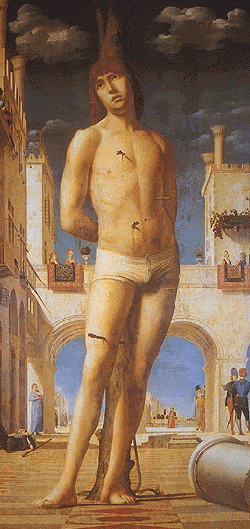

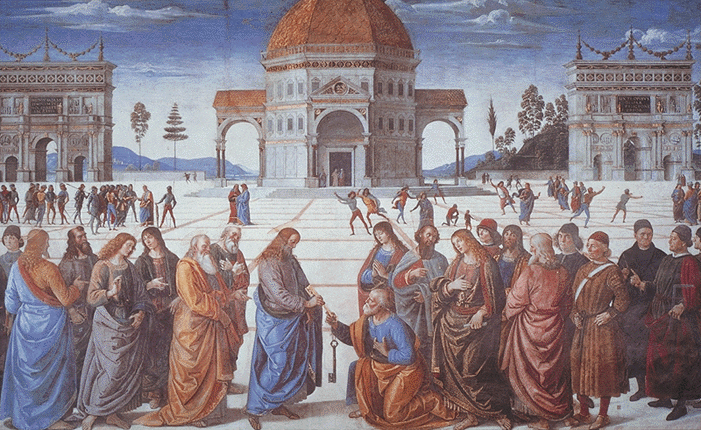

ATTRIBUTE. An object that is associated with a particular figure, like Cupid's bow or St. Peter's keys. These objects often symbolize something else or refer to events in the figure's life, as does a knife near St. Bartholomew, who was flayed alive. Artists often utilize attributes to help the viewer identify the figures. In the case of allegorical figures, attributes are the sole means of identification. For example, without her scales, the figure of Justice would have been impossible to identify, especially because a blindfold did not become one of her attributes until the sixteenth century.

Piero della Francesca's St. Michael

Michael, an archangel in the Jewish tradition who was made a saint in the Catholic Church, can be identified by the reference to the dragon he killed, by his sword and shield, and by his wings, which distinguish him from the other dragon-slayer, St. George.

ATTRIBUTION. Determination of the artist, school, nationality, or period of a work of art. Attribution is generally based on documentary evidence and/or a stylistic similarity to works of unquestioned identity

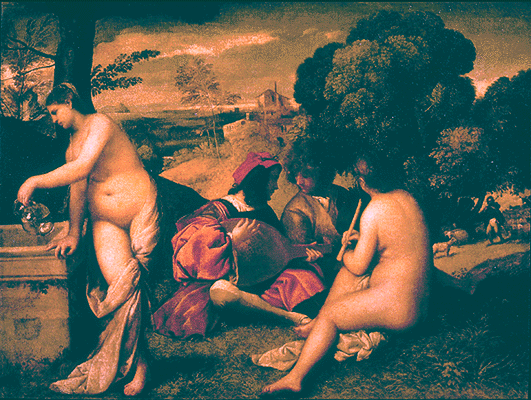

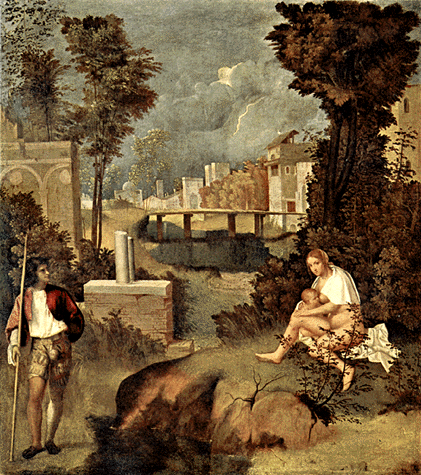

Giorgione's and/or Titian's Fête Champêtre, c.1508

Because Titian's earliest style was very similar to that of Giorgione, who he assisted early in his career, there has been some controversy over the attribution of this painting, which is generally credited to Giorgione.

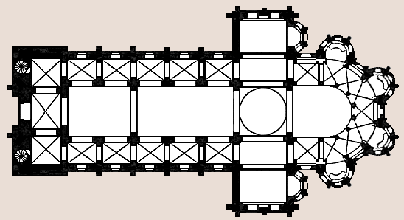

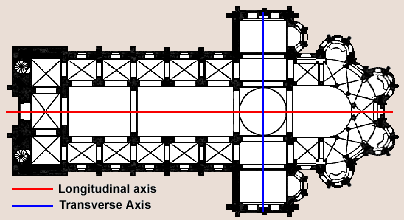

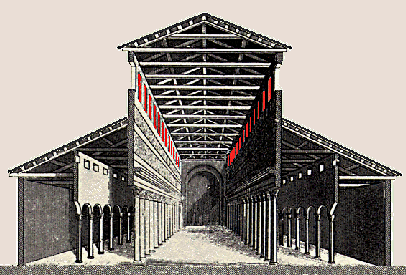

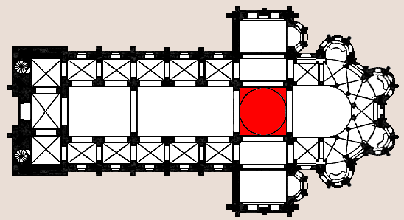

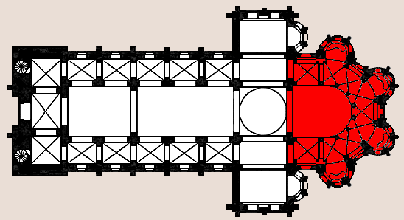

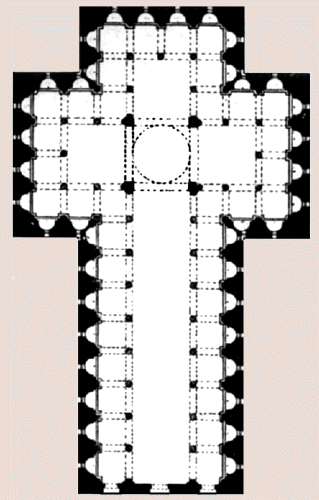

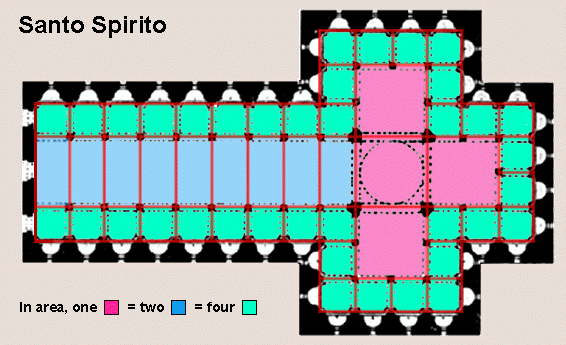

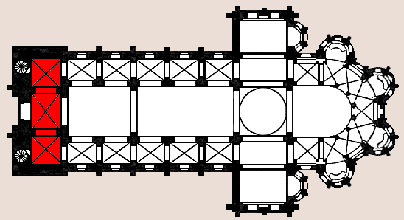

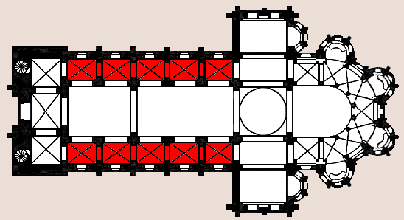

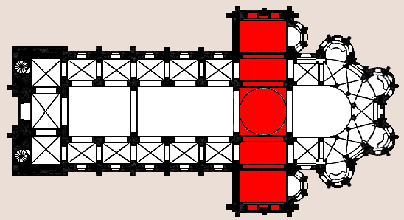

AXIAL PLAN. (Also called long- or longitudinal plan). Plan that is symmetrically organized along a horizontal axis. In ecclesiastical architecture, the axial plan is the basis of a type of church known as a basilica, which has a number of standard parts.

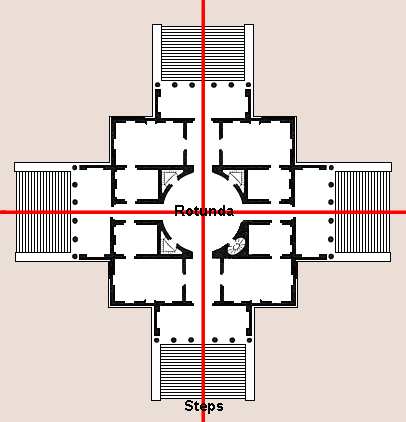

AXIS (pl. axes). Imaginary line around which a building or composition is organized. Centralized buildings have vertical axes.

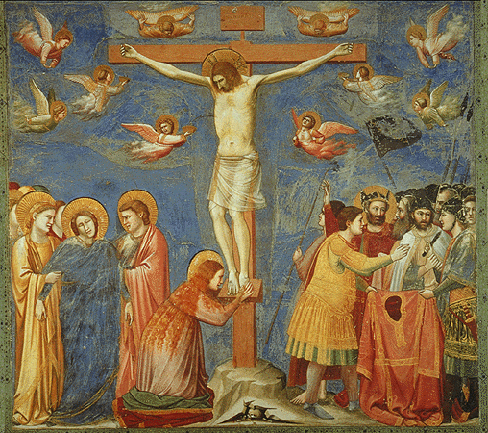

AZURITE. Blue mineral with greenish undertone, which can be ground into pigment. Its cost is far less than that of lapis lazuli. Azurite turns to dark green when used with buon fresco, and therefore, it must be applied after the plaster has dried. Because it is not bonded with the plaster, the color has a tendency to flake off.

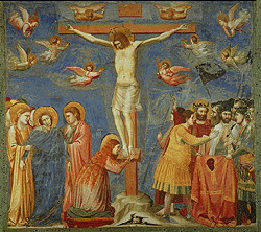

Giotto's Crucifixion, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305-6

![]()

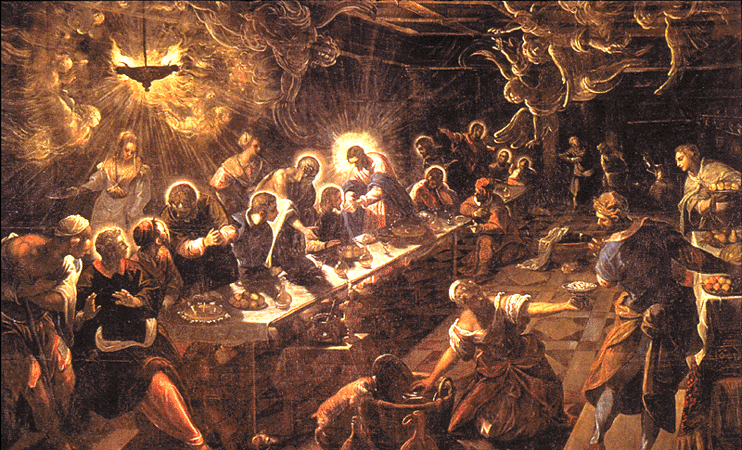

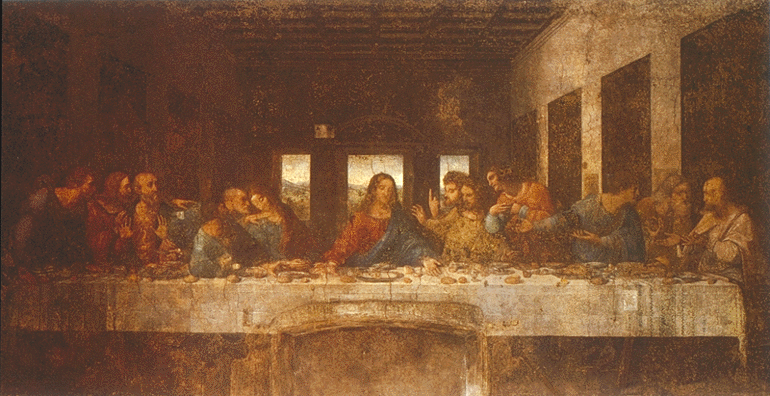

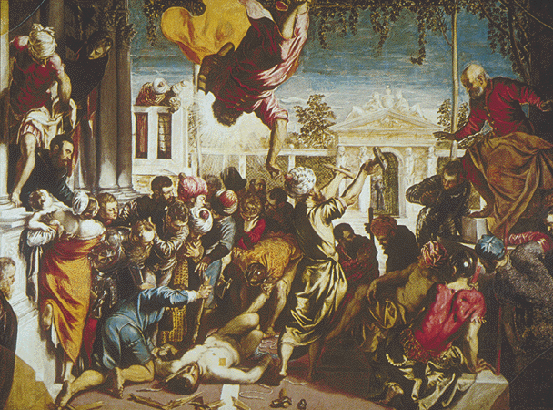

BACK LIGHTING. A technique whereby figures in a painting are lit from the back, producing silhouette-like images. Tintoretto was particularly fond of this technique.

Tintoretto's Last Supper, 1592-94

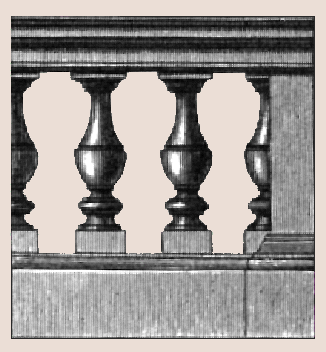

BALUSTER. Support that is used in a series to hold the handrail of a balustrade. In form, balusters are generally circular in section and often resemble slender urns.

BALUSTRADE. Railing composed of a handrail supported by a series of balusters, supports that often resemble elongated urns. Reinforcing members such as small piers often add support at the ends and at regular intervals.

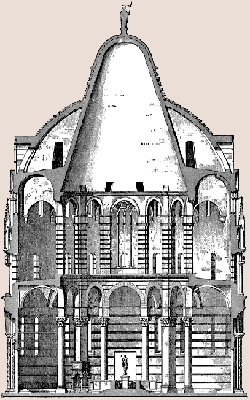

BAPTISTERY. Building or room of a church where baptismal rites are performed. Early baptisteries were separate from churches because the early form of this ceremony involved immersion in tub-sized basin, which became the building's central focus. Although the adoption of sprinkling in the ninth century meant that it was no longer necessary to maintain a separate structure to house the basin, free-standing baptisteries continued to be built in Italy until the end of the Middle Ages. In plan, they were generally circular like the Baptistery of Pisa Cathedral or octagonal like the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral. The use of eight-sided plans was a deliberate reference to the seven days of Creation plus an eighth day of Resurrection. These themes were often illustrated by the decoration of baptisteries.

Section of the Baptistery of Pisa Cathedral

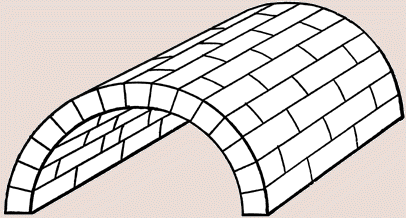

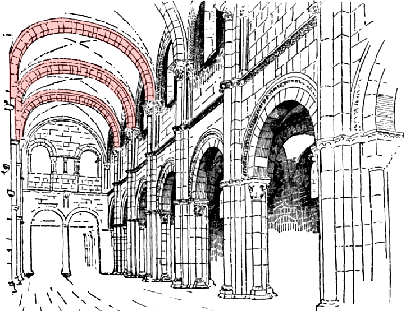

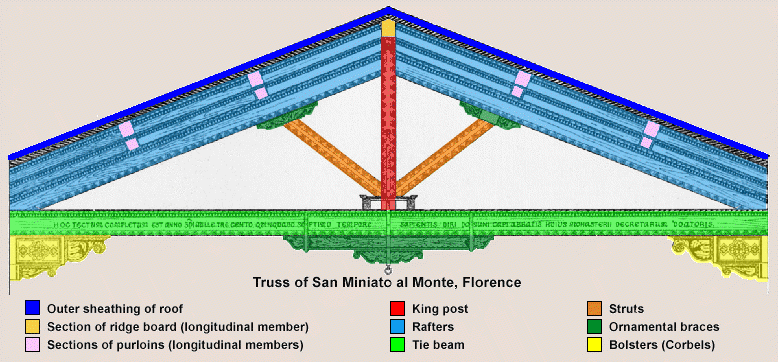

BARREL VAULT. Arched masonry ceiling that follows a semicylindrical course. Also called a tunnel vault.

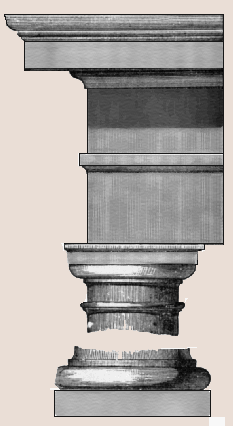

BASE. In classical architecture, the bottom unit of a column or pilaster, which rests on the floor or a pedestal base.

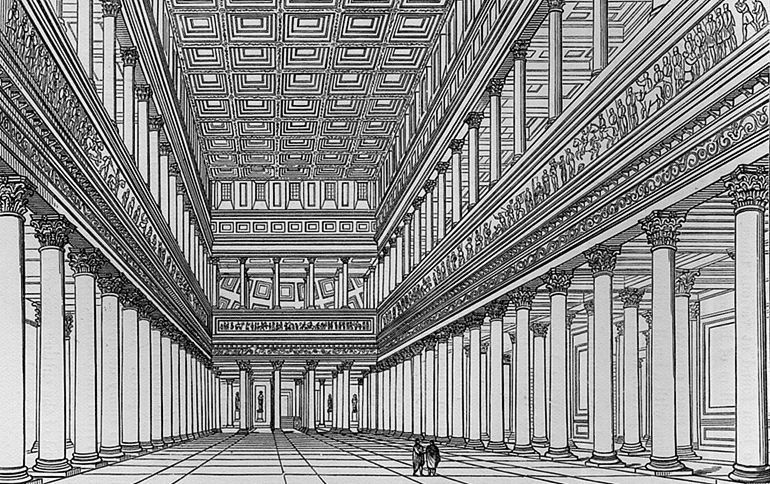

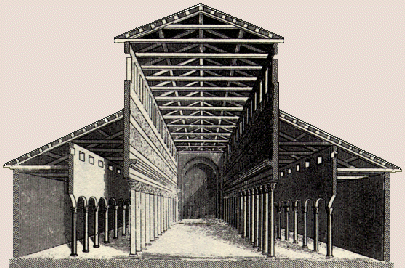

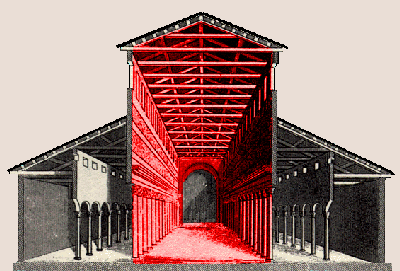

BASILICA. Form of axial-plan building that was derived from an ancient Roman law court and adopted and modified for Christian churches. The basilica has a central nave that terminates in an apse. On each side are one or two side aisles, whose shorter height makes it possible to light the interior with clerestory windows. In Early Christian times, the basilica was expanded by the addition of a transept, which gives the plan a Latin-cross shape.

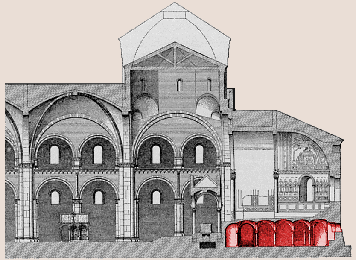

Section of Old St. Peter's, Rome, c. 324-30

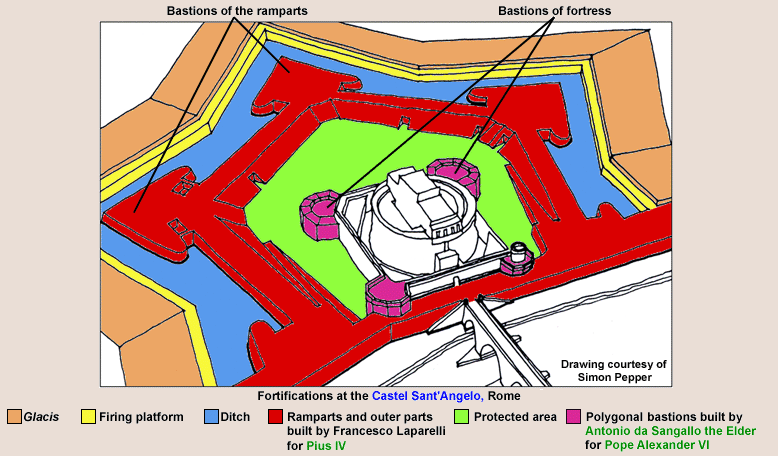

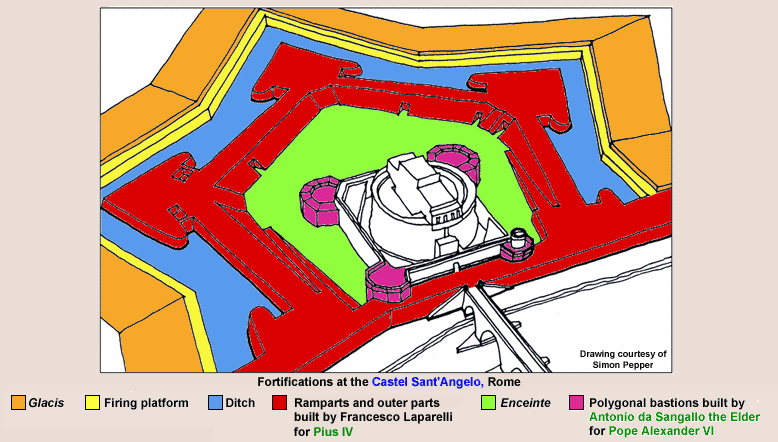

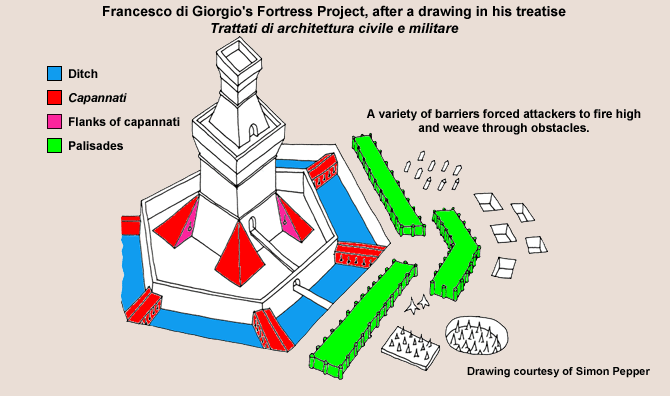

BASTION. Structure that projects from a fortified perimeter at corners or at intervals along a straight wall. Bastions held the men and weaponry needed to defend the intervening sections of wall from attackers. A platform roof accommodated cannon, which fired through ports in the parapet, a low wall along the roof edge. Part of the interior of the bastion contained chambers that were built to hold cannon and other weaponry. Adoption of an arrowhead shape eliminated the blind spots in the coverage from flanking fire.

BAY. Subdivision of a building according to the spacing of supporting members like columns or piers. In vaulted construction, vaults correspond to bays.

Brunelleschi's Foundling Hospital, Florence

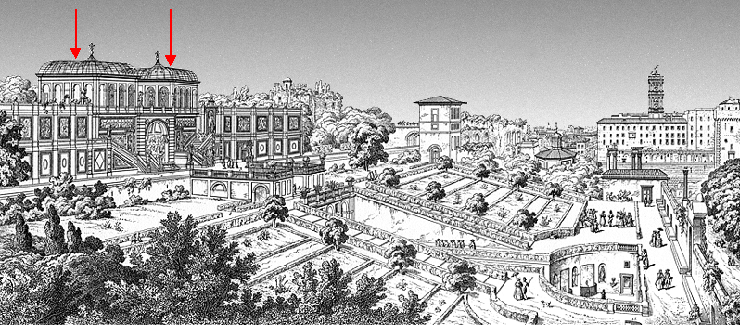

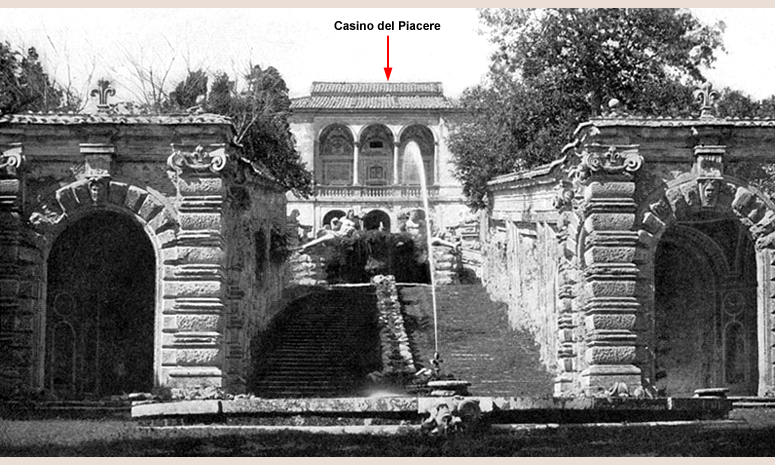

BELVEDERE. Open pavilion or tower that has a prominent view due to an elevated location. It may be free-standing or mounted on the roof of a building.

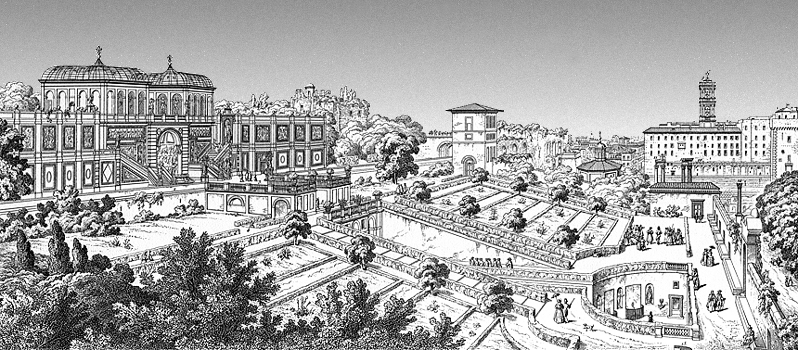

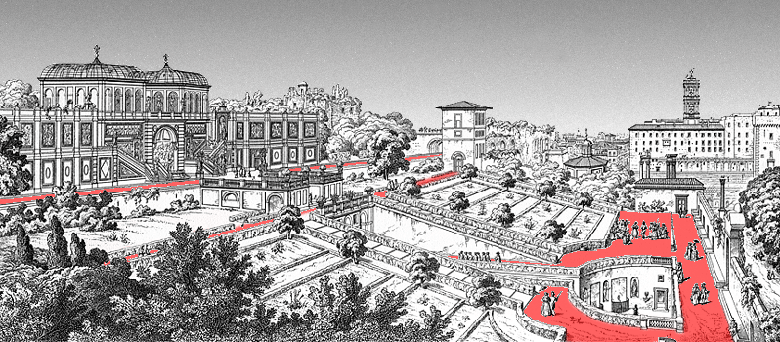

Orti Farnesiani, Rome, Vignola, c. 1570-73

BIAXIAL. Having two dominant axes, which are usually at right angles to each other.

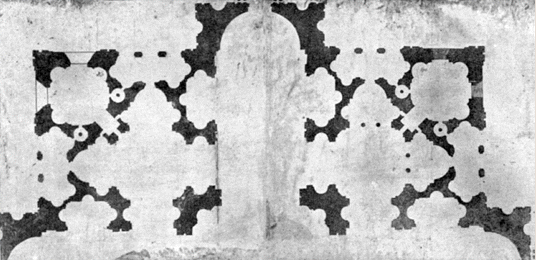

Plan of Palladio's Villa Rotonda, 1566-after 1580

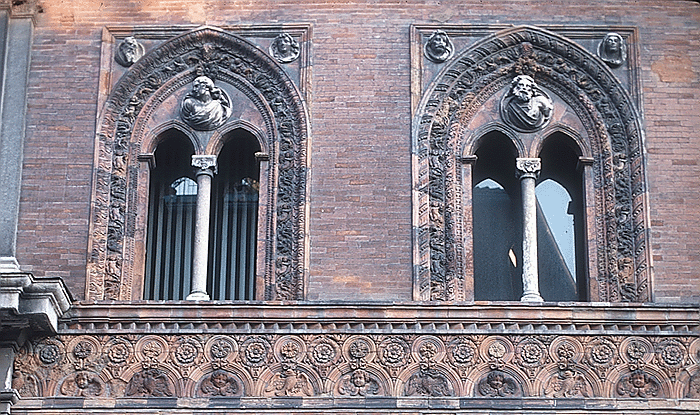

BIFORATE WINDOW. Arched window that is divided by a mullion into two vertical arched lights. In the Early Renaissance, the mullion of biforate windows was often in the form of a colonette. The pointed-arch versions typical of Italian late-Gothic buildings were succeeded by round-arched versions in the fifteenth century. The space above the two lights usually contained a relief-carved medallion, but at Alberti's Palazzo Rucellai and Codussi's palaces in Venice, this space was pierced by a small light. In ornamentation, biforate windows range from plain to highly decorative.

Detail, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, 1489-1536

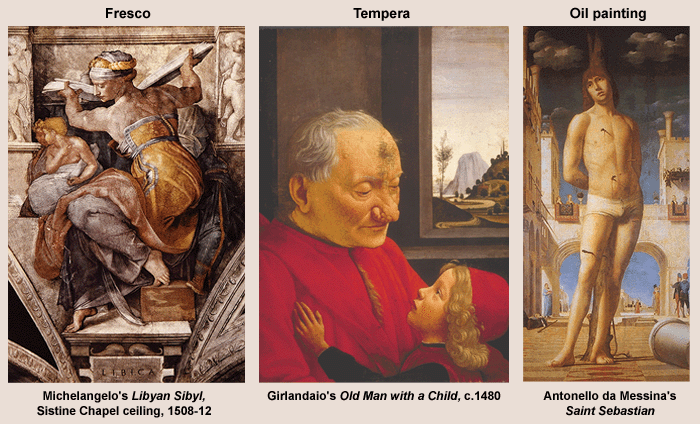

BINDER. The ingredient of the medium that promotes adhesion of the particles of pigment within the paint itself to the surface to be painted. Egg, glue, and oil were used as binding agents in the Renaissance.

BLIND ARCH. Closed arch. Blind arches are formed when an arch is filled or attached to a solid wall.

BOLE. Red-clay layer applied to a panel on areas that are to receive gold leaf.

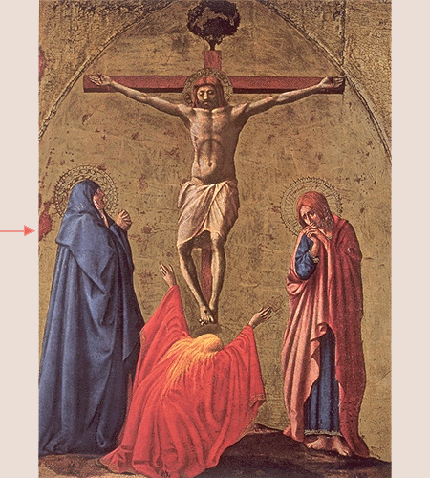

Areas of bole can be seen where the gilding has come off in Tommaso Guidi's Crucifixion.

BOND. The laying of brick or stone so that the joints do not align and the pieces hold each other in place. When more than one thickness of brick or block is used, the bond can run laterally as well.

BOTTEGA. In art history, the physical workplace or the particular group formed by a master, his assistants, and his apprentices. Bottega means "shop" in Italian.

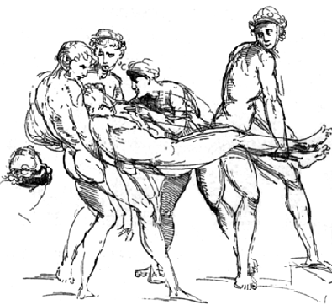

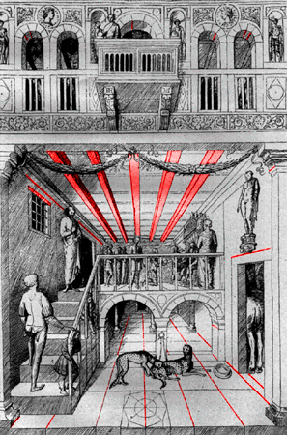

Engraving of Bandinelli's bottega (workshop)

BRILLIANCE. In color theory, the lightness or darkness of a color. Also called value.

BROKEN ENTABLATURE. Entablature that projects forward at the points where columns or pilasters stand in front of the wall. See ressaut.

BRONZE. Alloy of copper and tin that was suitable for casting or working cold (hammering, engraving, etc.). Although both metals are soft and malleable, combining them produces a new hardness that is greater when more tin is present. Tin content usually ranges from 16 percent for alpha bronze to 32 percent for delta bronze. Color and patination (finish developed over time) were affected by the proportions of the two metals and any others that were included like zinc and silver. In the Renaissance, bronze was used for a variety of practical devices like tools and armaments. In architecture, it was used for hardware like lamps and rings and for doors like Ghiberti's "Gates of Paradise" on the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, which were decorated by gilded bronze relief panels. Bronze was especially well suited for free-standing sculpture. It was far more expensive than marble, but bronze's tensile strength made it more suitable than stone for works having large unsupported extensions or slender supporting members. Because it shrinks as it cools, solid casting of bronze is only suitable for small works like figurines. Thicker pieces like portrait busts or whole figures, which were often cast in several parts, were hollow cast.

BUON FRESCO (Italian words for "true" and "fresh"). Painting done on wet plaster.

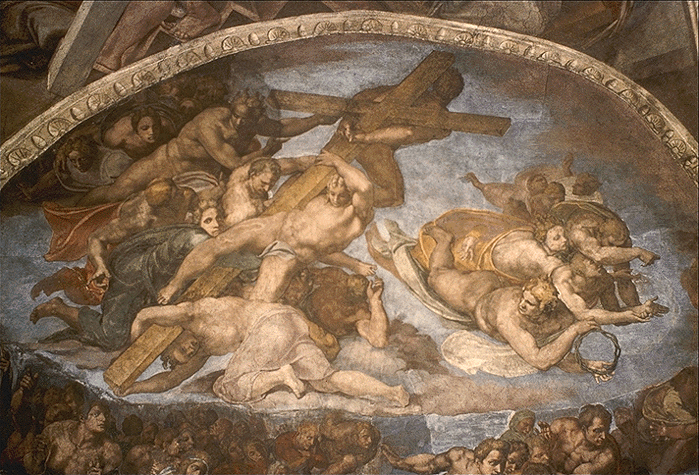

Michelangelo's Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, 1534-41

BURNISHED. Polished to a smooth finish by rubbing with a tool called a burnisher.

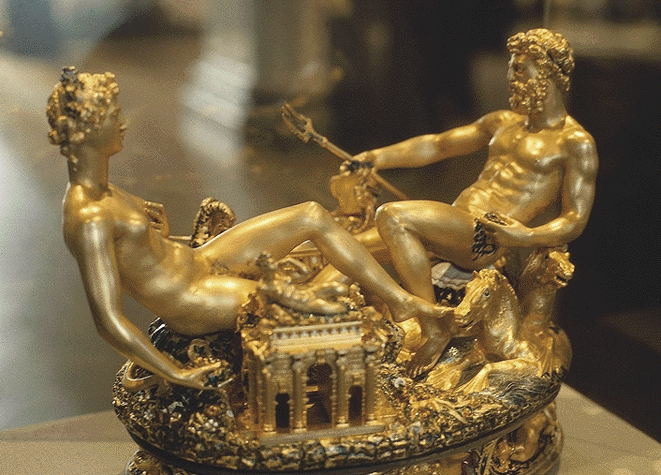

Benvenuto Cellini's Saltcellar of Francis I, 1539-43

BUTTRESS. Support, usually of masonry, that counteracts the outward thrust of an arch, vault, or other roof system. Piers abutting a wall are a common form of buttress. Also see flying buttress.

![]()

CABINET PAINTING. A small painting intended to be hung in private quarters and viewed up close.

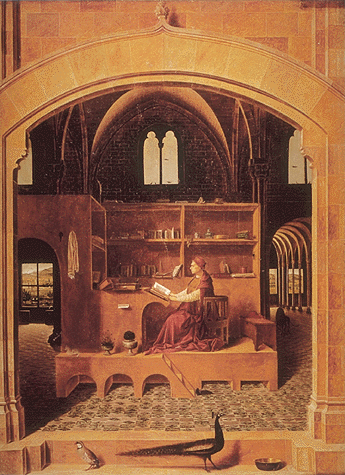

Antonello da Messina's St. Jerome in His Study, 18"x14", c. 1455-75

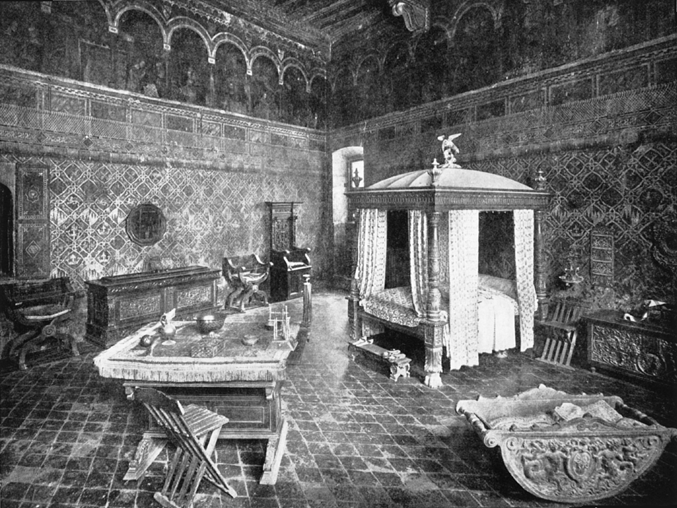

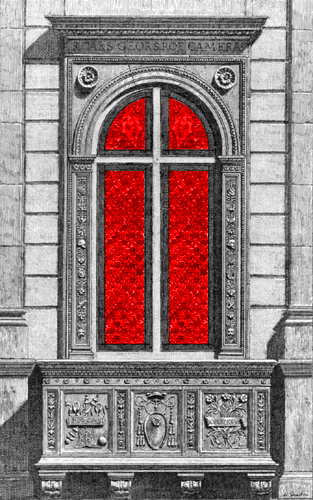

CAMERA. Chamber, especially a personal bedchamber, which was often separated from the more public rooms like the salone.

Davizzi-Alberti Nuptial Chamber, Palazzo Davanzatti, Florence, c.1330s

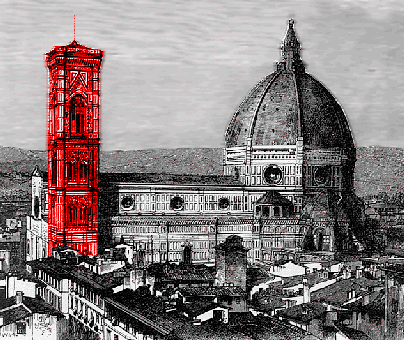

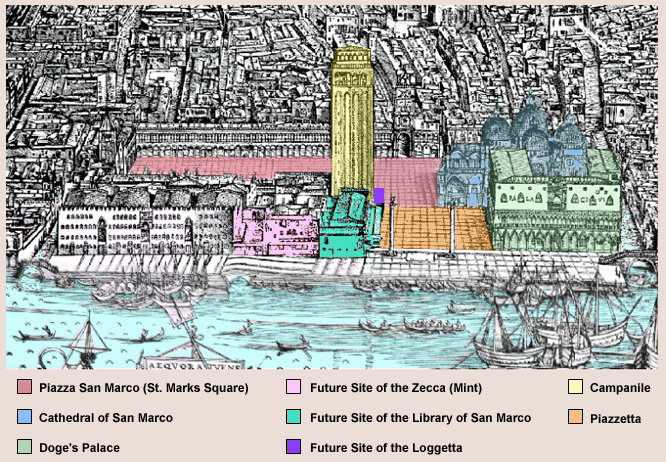

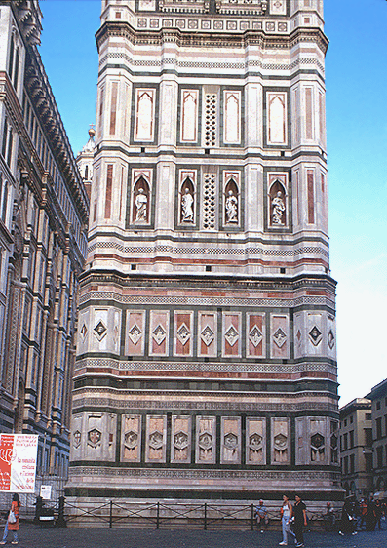

CAMPANILE. Bell tower. The name comes from the Italian word campana, which means "bell." In medieval Italy, the bell tower was usually separate from the church it served. It often stood on a piazza in front of the church, but sometimes it stood behind it, as it does at Pisa Cathedral. At Siena Cathedral, the bell tower is part of the church. The exterior treatment of bell towers was usually similar to that of the church and baptistery. This is illustrated by the campanile and church of Florence Cathedral, which are both faced with patterns of white, green, and rose marble. Because medieval bell towers often remained in good condition far longer than churches, many of them still stand next to Renaissance churches.

CANGIANTISMO. Use of different hues (colors) for the shades and highlights of a single item or color zone, like a robe whose light areas are green and dark areas are brown. The term derives from the Italian adjective cangiante, commonly used since the Renaissance to describe a particular type of silk fabric, sometimes called "shot silk", that changes color according to the direction of the light cast upon it. The fabric was often used in clothing for the wealthy, and thus is also common in art. It still shows up from time to time in twentieth-century Italian fashions.

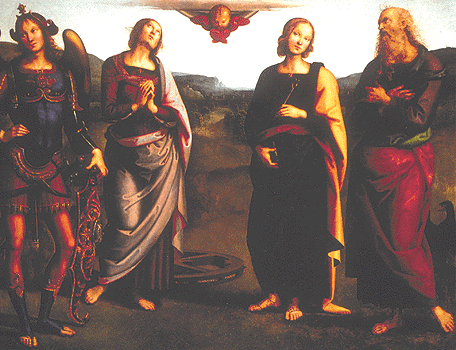

Detail of Perugino's Virgin and Child with Saints, 1497

CANVAS. Durable fabric woven of linen, cotton, jute, or hemp, which is a suitable surface for painting on after it has been coated with a non-absorbent substance and stretched taut over a frame. In Renaissance Italy, painters used linen coated with a thin layer of gesso, which created a smooth support. In the late 15th century, artists such as Botticelli and Mantegna, used tempera on canvas. In the 16th century, oil paint, which had been introduced in Venice in 1475, became widely used on canvas.

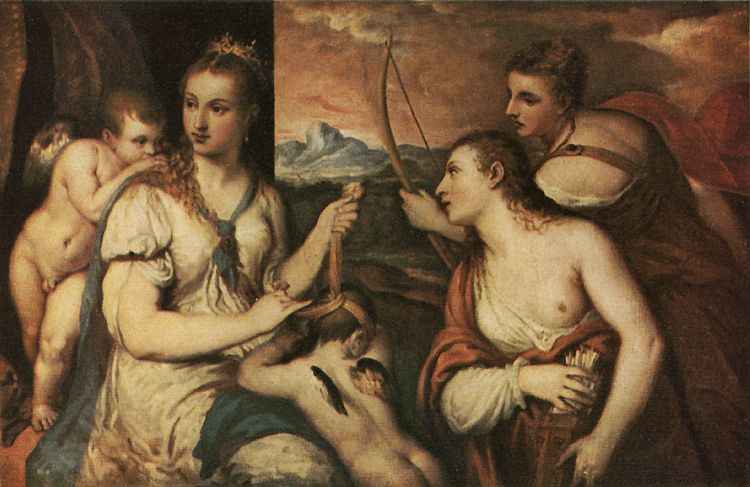

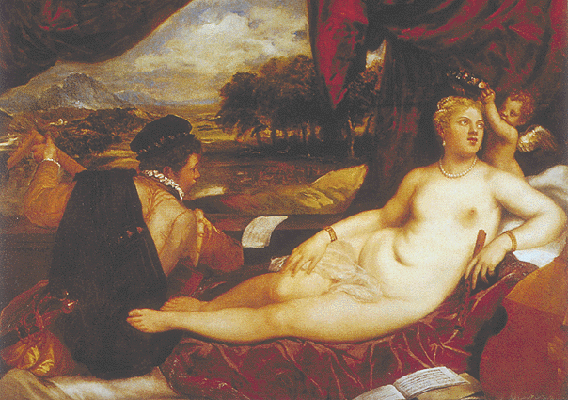

Titian's The Education of Cupid, oil on canvas

CAPANNATO. Small blast-resistant structure containing artillery. Capannati could be placed at the corners of strongholds or across ditches, where they also facilitated communication between the forward and rear lines of defense. Free-standing capannati could be placed in ditches and on platform roofs. This form was replaced by modern casemates with integrated raised gun platforms by the middle of the sixteenth century.

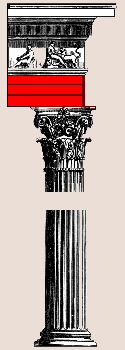

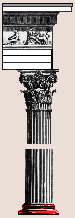

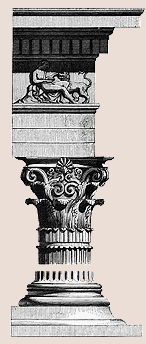

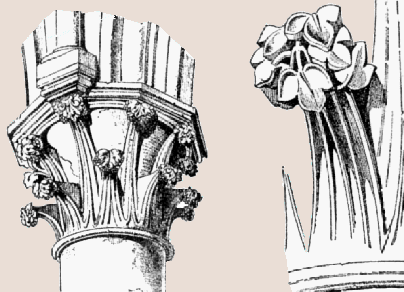

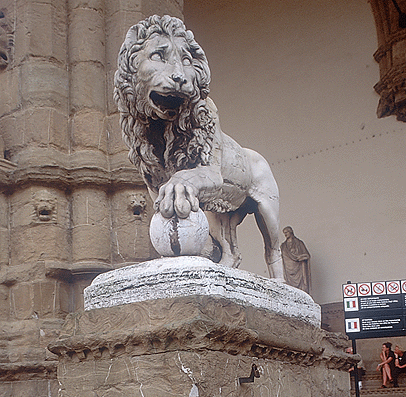

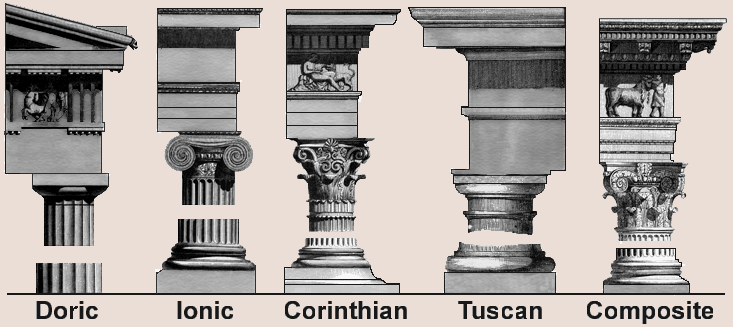

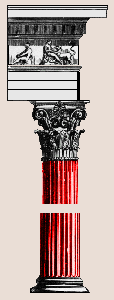

CAPITAL. The upper member of a column, which makes the transition from the cylindrical column shaft to the straight entablature above.

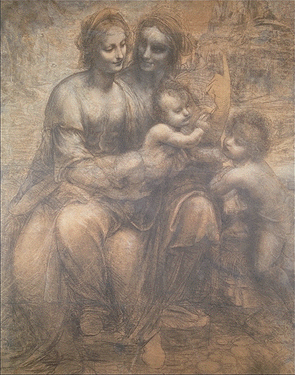

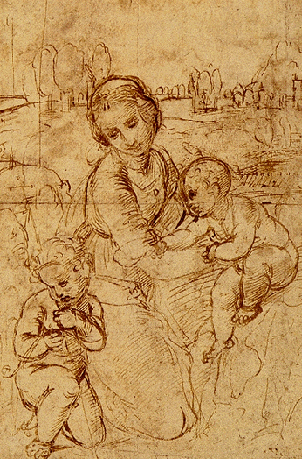

CARTOON. 1) A highly finished drawing like Leonardo's famous cartoon of the Virgin and child with St. Anne. 2) A full-size, fully worked-out drawing on paper functioning as a model for a painting or tapestry. The drawing could be transferred to the surface to be painted by several methods.

Indentation. When the painting is to be a fresco, the outlines of the drawing can be slightly indented into the wet plaster by pressing a tool along the lines of the drawing. (The drawing is cut into pieces corresponding to the giornate.)

Chalk transfer. When the painting is to be executed on panel, the back of the drawing can be coated with chalk so that retracing the outlines on the front would press chalk outlines onto the panel's surface.

Pouncing. Either fresco or panel can be marked by "pouncing," a process in which colored powder could be pressed through holes punched along the outlines of the drawing.

Leonardo's Cartoon for Madonna and Child with St. Anne and the Infant St. John, c. 1499

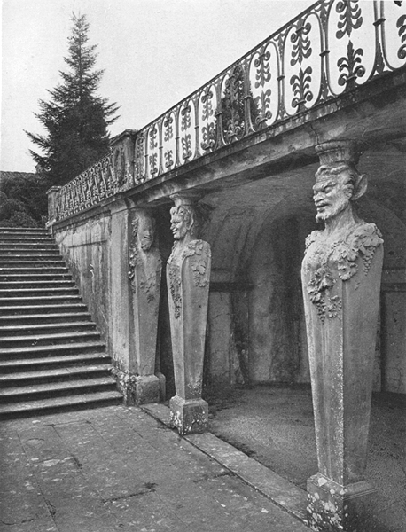

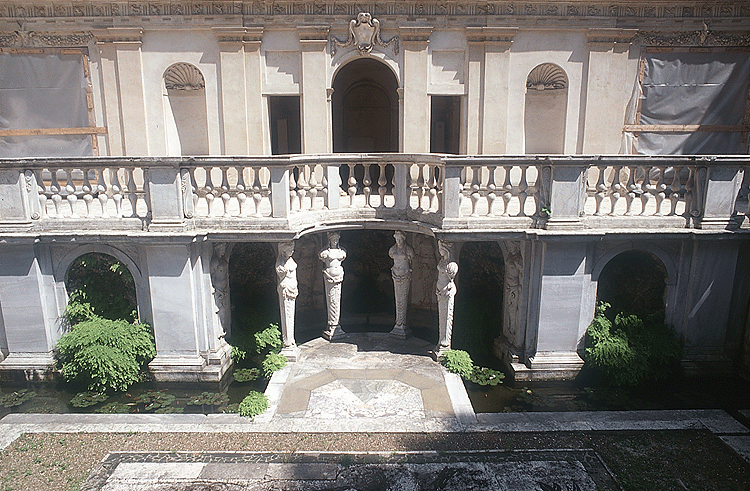

CARYATID. Statue of female figure used as a column. The less-common male equivalent is variously known as an atlantid, an atlas (pl. = alantes), and a telamon. "Terms" are variants of caryatids and atlantes in which the head and shoulders or head and torso are joined to a downward-tapering pedestal. Terms can be either male or female. A similar form for males having only the head or head and shoulders is called a herm.

Porch of the Maidens, the Erechtheion on the Acropolis, Athens, 421-405 BC

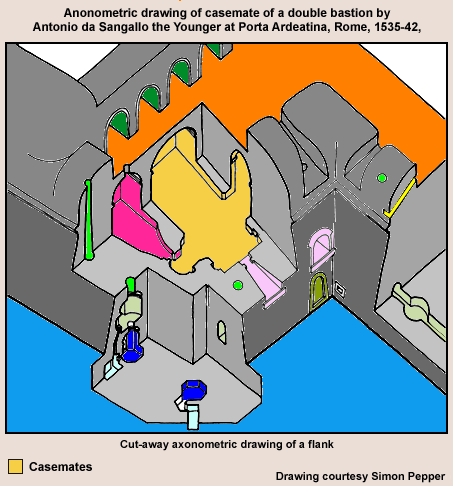

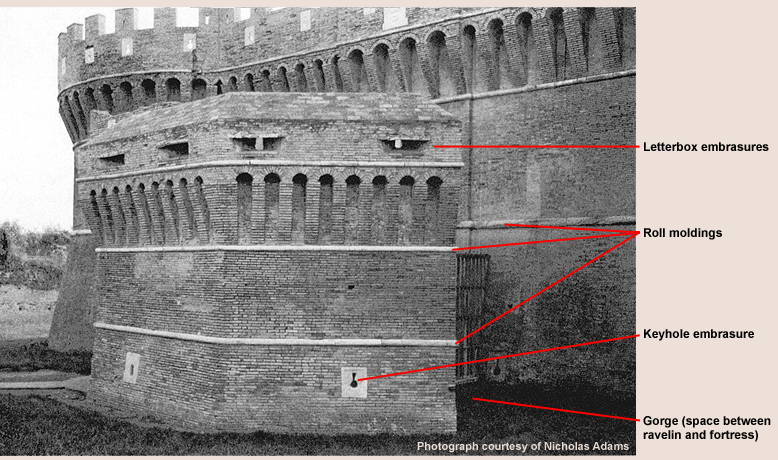

CASEMATE. Blast-resistant vault built into a wall or rampart to provide cover for soldiers firing large guns through embrasures. In bastions, where the firepower was concentrated, casemates were generally used on multiple levels. Having a concentration of firepower compensated for the slowness between rounds.

|

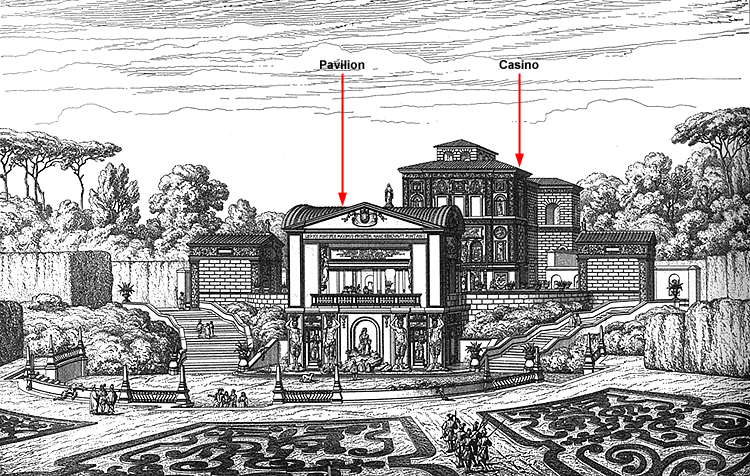

CASINO (pl. casini). Structure in a garden that often housed a collection of objects and was used for social gatherings, which often included music and dance. Although the term "casino" is sometimes applied to a villa's main building, it usually indicates a secondary structure.

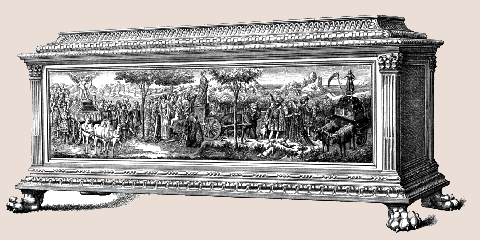

CASSONE (pl. cassoni). Chest used for storing clothes and linens as illustrated in the background of the Venus of Urbino. Cassoni functioned as closets in Renaissance Italy and were often given to brides. Since such chests were regarded as prized possessions, their panels were often decorated inside and out by paintings or carvings.

CASTING. The making of a statue or relief by pouring molten metal (or some other liquid that dries hard) into a mold. The still-in-use cire-perdue (lost wax) method of casting and the use of bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), which is still the preferred metal for casting, both date back to the third millennium BC. The cire-perdue method involves creating a mold by encasing a wax model (form to be imitated) in plaster or some other malleable material that becomes rigid and heat resistant when dry. After being heated, the wax drains out, and molten bronze is then poured into the cavity. After the bronze cools, the plaster mold is removed, and the surface is worked to remove mold marks, produce the desired smoothness, and create details. Casting may be solid or hollow core. Solid casting, which is simpler than hollow casting since it can be achieved using a coreless wax model, is only suitable for casting small objects because large volumes of molten bronze cool unevenly, producing distortion. In hollow-core casting, which solves this problem and reduces the amount of bronze needed, the wax model is formed on a heat-resistant core that often remains inside the final work. Pins project from the core into the plaster mold to prevent the core from shifting in the mold after the wax layer is drained away. A bronze shell is created by this method because the wax is only a layer between core and mold.

CAST SHADOW. Shadow extending from an object on the side opposite the source of light.

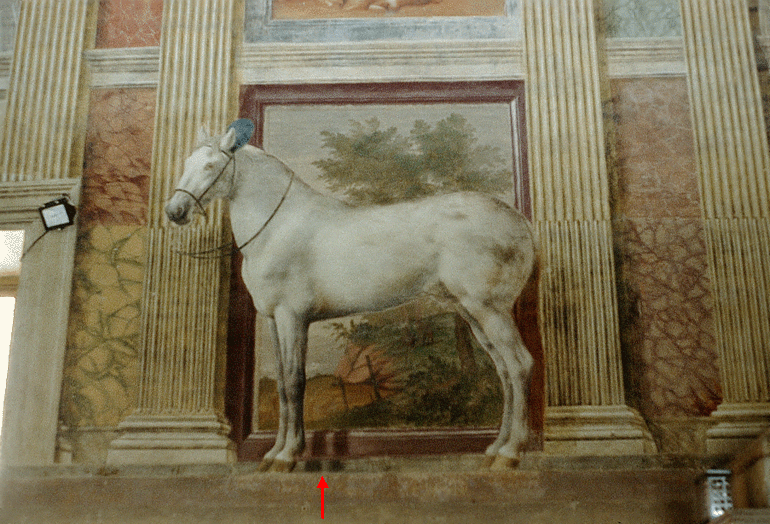

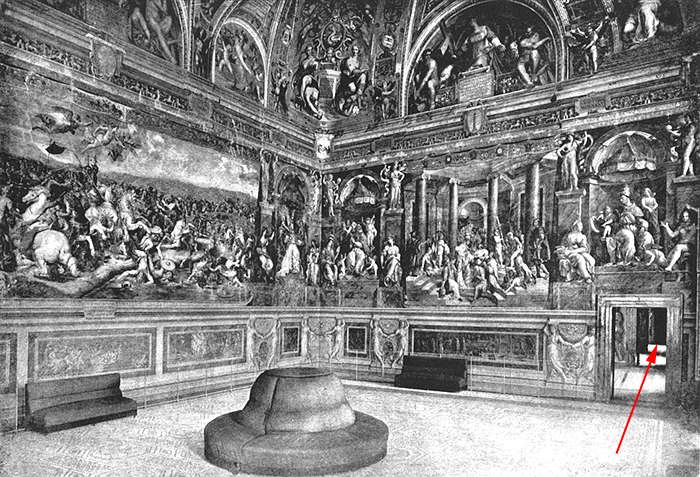

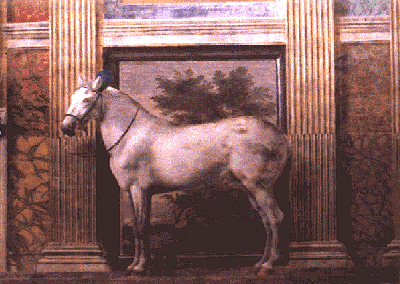

Detail of Giulio Romano's Sala dei Cavalli, Palazzo del Tè, Mantua

CATHEDRAL. Head church of a diocese (church district). The name derives from the term "cathedra" and refers to both the office and the official throne of the bishop, who is in charge of all the churches within his diocese. The bishop's throne was traditionally placed in the apse, just as the presiding magistrate's throne had been Roman times when the basilica functioned as a court of law. The Cathedra Petri in St. Peter's was long believed to have been the original throne of St. Peter, the first bishop of Rome.

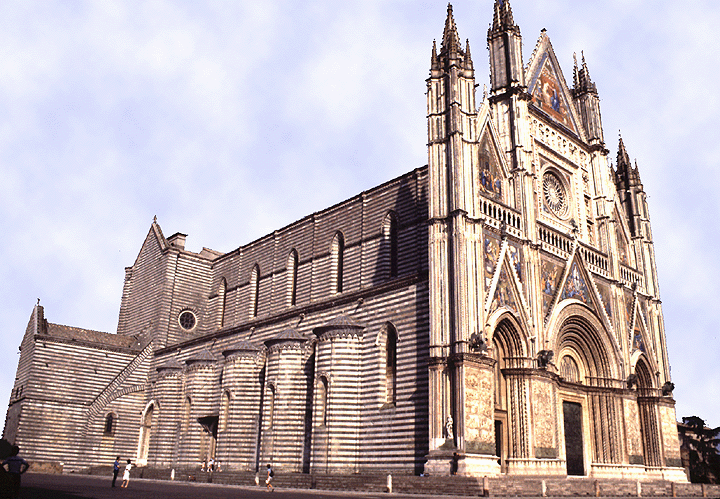

Orvieto Cathedral, begun 1290

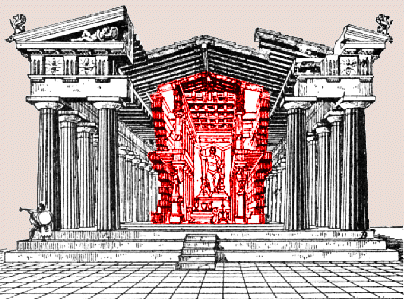

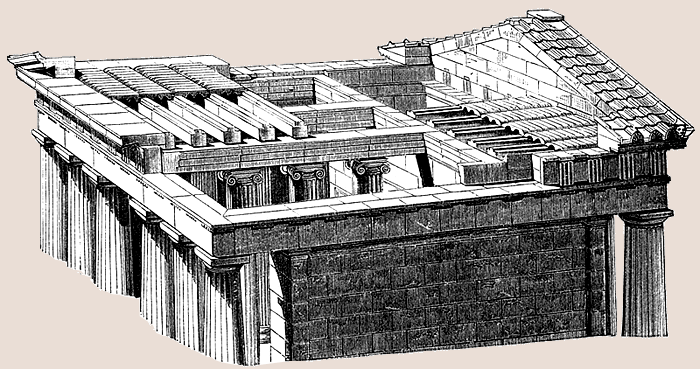

CELLA. The enclosed portion of an ancient temple where a statue of the cult deity was kept.

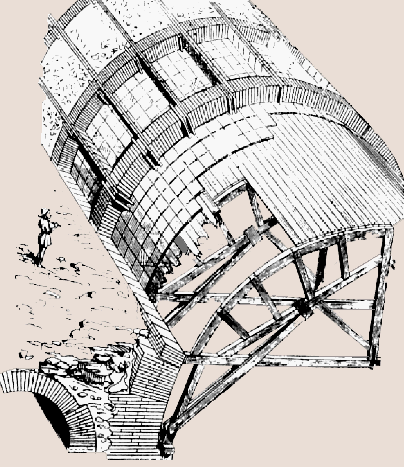

CENTERING. Arch-shaped wooden framework that is used for the temporary support of an arch or vault under construction.

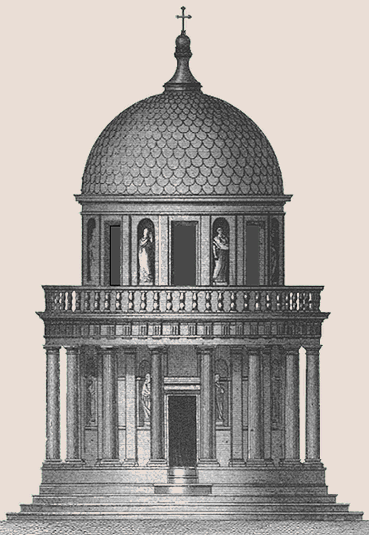

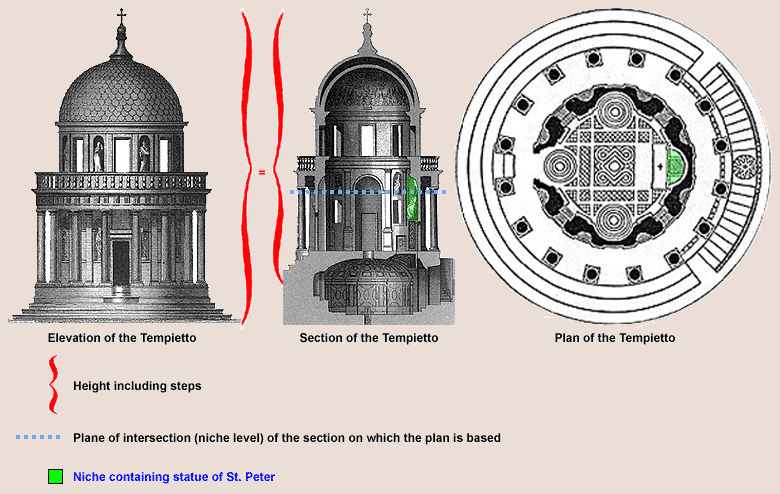

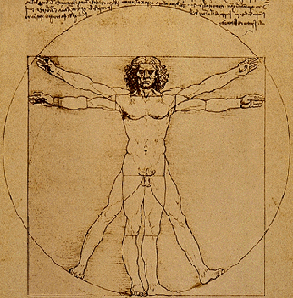

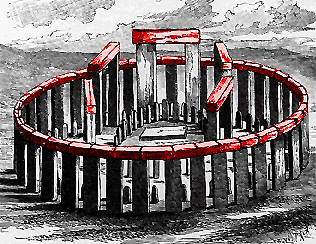

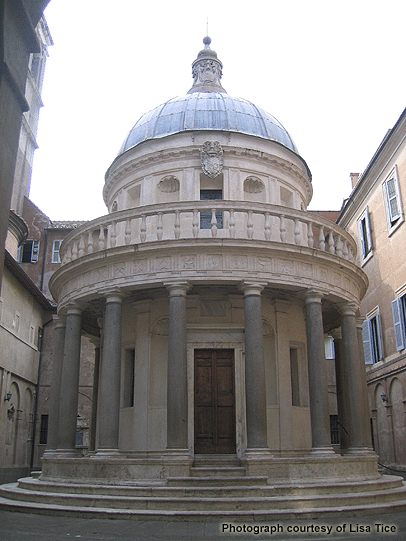

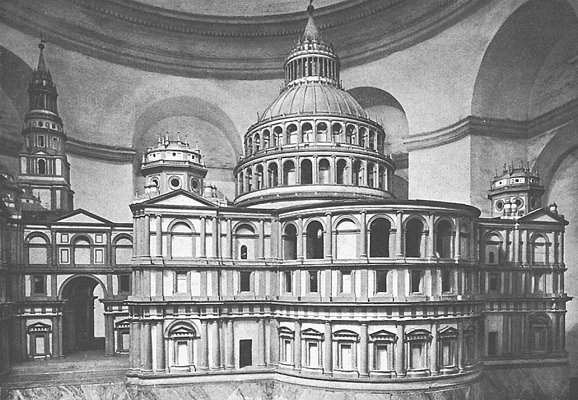

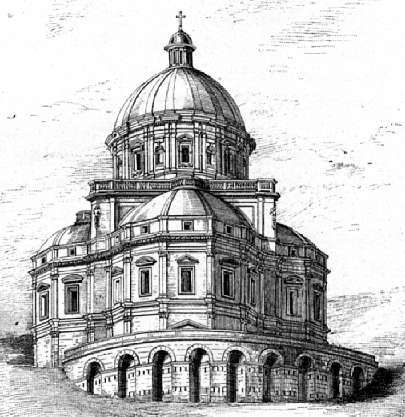

CENTRAL PLAN. Type of plan or building that is organized around a vertical axis. This form is distinct from the axial plan, which is organized along a longitudinal axis. In southern Europe, centralized structures date back to ancient tholoi, circular Greek tombs, a category that has been expanded to include other ancient circular structures like tombs and temples. In Greek and Roman architecture, round temples usually included circular peristyles, the Pantheon being a famous exception. In being formed by an edge that is continuously equidistant from an invisible center, the circle was considered to be the most perfect of geometrical figures, and as such, the most suitable form to mirror the perfection of God, who was seen as the creator of a universe whose physical laws embodied an internal harmonic proportion. Adoption of centralized plans for churches was usually opposed by the clergy, who found axial-plan churches to be better suited for processions and separating the clergy from the laity. In the Renaissance, centralized designs were most often used for chapels and votive churches, which had different functional requirements from parish churches. |

Bramante's Tempietto, designed c. 1502 |

CHALK. Soft stone of calcium carbonate that occurs in white, black, and red. Although chalk is similar to charcoal in producing a broad, continuous line, it is less apt to smudge or rub off. Red and black chalk, which came into use in the late fifteenth century, were favored drawing media of Leonardo and Michelangelo. White chalk was primarily used for highlights in drawings made with red or black chalk.

Andrea del Sarto, Study for Child's Head

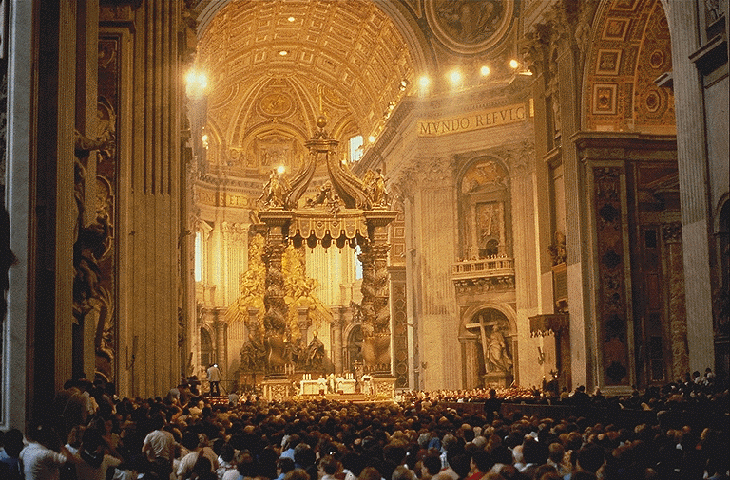

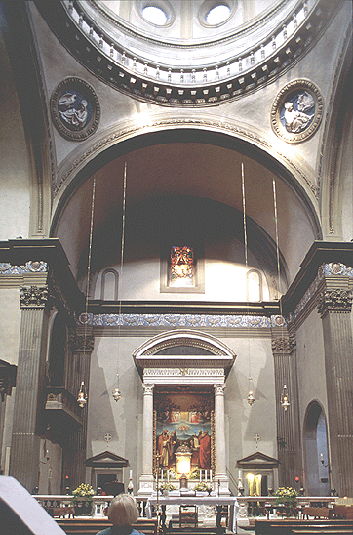

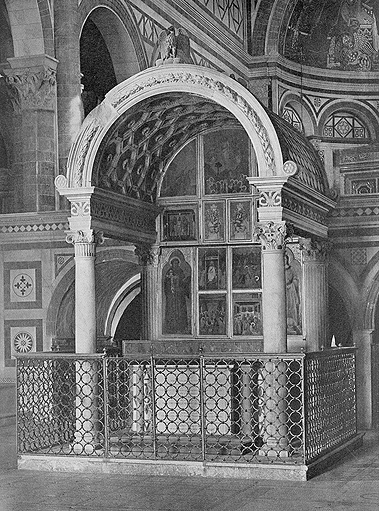

CHANCEL. The part of a church containing the main altar and, sometimes, the choir. Before the Council of Trent advised that worshipers in the nave should have an unobstructed view of services in the chancel, a chancel screen often stood between the nave and the chancel.

St. Peter's, Rome

CHARCOAL. Drawing material made from charred wood. The hardness of the charcoal varies with the closeness of the wood's grain. Charcoal is often used on soft grainy paper whose texture allows the artist to control the darkness or lightness by applying more or less pressure. A drawback is that it easily comes off the drawing surface unless it is sealed by a fixative like shellac. Its transient quality was beneficial at times because unwanted lines could be removed after desirable ones were traced over in a permanent material like ink or paint. This procedure was described around 1400 in Cennini's Il Libro dell'arte, a manual on painting.

Tintoretto's Study of a Wedding Figure

CHASING. Final finish given a work of cast metal to remove surface blemishes. 2. Ornamenting a metal surface by engraving with a stylus or hammering against a punch.

Benvenuto Cellini's cast bronze Portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici

CHEVET. French term for a church east end that is apsidal in form and includes a choir, an ambulatory, and radiating chapels.

CHIAROSCURO (from the Italian words for "light," chiaro, and "dark," scuro or oscuro). Use of light and shade in a manner that creates the illusion of three-dimensional volume and relief.

Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks, begun 1483

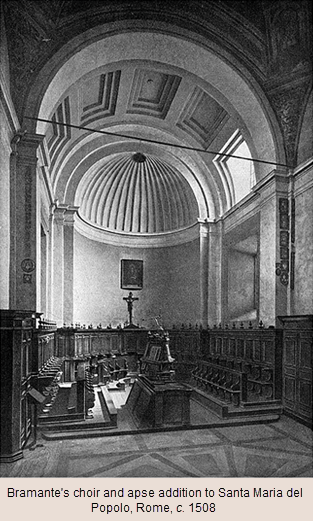

CHOIR. The part of the east end of a church where the singing and chanting of services takes place. This space, which is often located between the crossing and the apse, is generally reserved for the clergy.

CINQUECENTO. Italian term for the sixteenth century, which literally means "five hundred" but carries the meaning of "the 1500s."

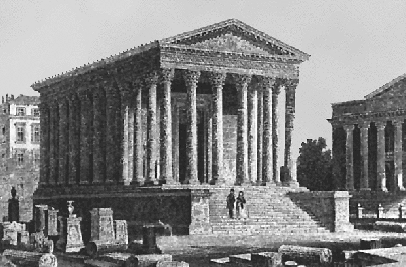

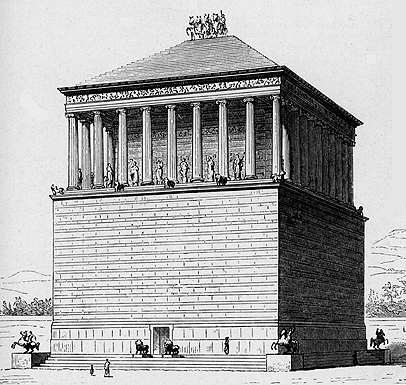

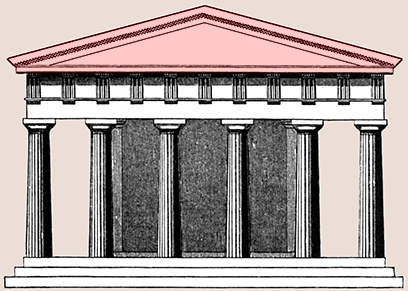

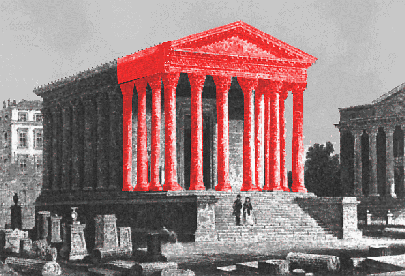

CLASSICAL TEMPLE. Greek or Roman temple that was usually rectangular or circular and enclosed a cella. It had a shallow-pitched roof whose gables were articulated as pediments. Classical temples were entered through porticos supported by columns.

Maison Carée, Nîmes, France

CLERESTORY (also spelled "CLEARSTORY"). Window-filled zone of wall located between an upper roof and a lower lean-to roof. In Renaissance architecture, clerestories were commonly used on basilican churches between the nave and side-aisle roofs.

Section of Old St. Peter's

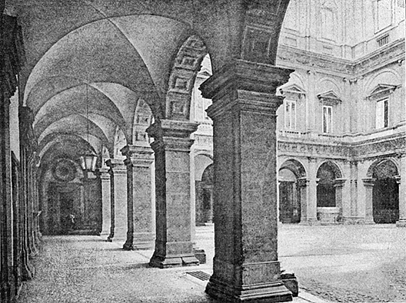

CLOISTER. In architecture, a courtyard that is attached to a church or monastery and lined by a covered walkway whose open side is usually supported by an arcade or colonnade.

Michelozzo's Cloister of San Marco, Florence

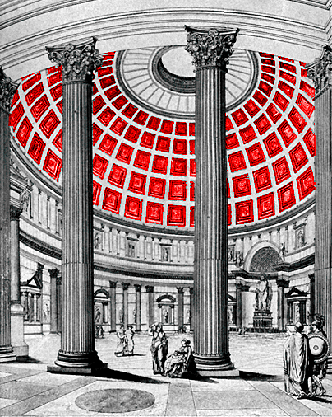

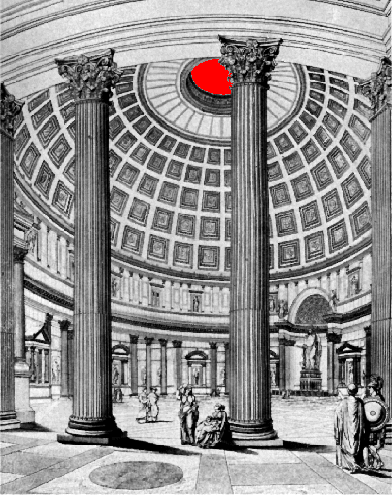

COFFER. A recessed panel of a vault, dome, flat ceiling, or other downward-facing surface. Because the panels are thinner than the framework, the ceiling weight is reduced. In concrete construction, coffering is achieved by placing geometrically shaped forms, like a stack of flat square units of decreasing expanse, on the centering or surface onto which the concrete is to be poured.

Pantheon, Rome

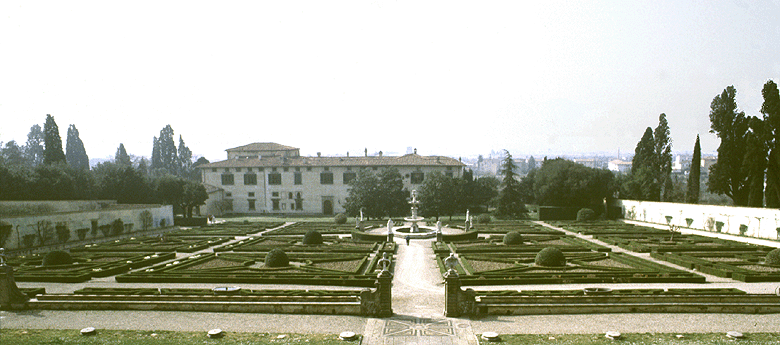

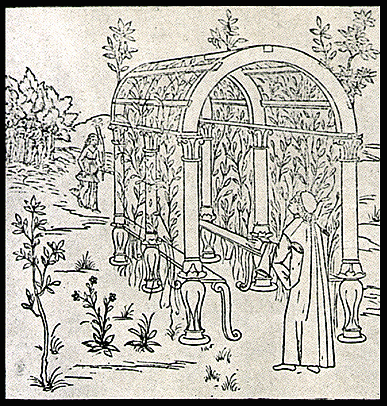

COLLECTION GARDEN. Type of garden whose plants are chosen for their value as specimens rather than for their aesthetic contribution to the overall design. The popularity of such gardens in the Renaissance reflected a new interest in both collecting per se and in the scientific examination of the physical world. Collection gardens were used both as types of self-contained gardens and as subsections of larger, multi-featured gardens.

Reconstruction of Vignola's Orti Farnesiani, a collection garden, designed c. 1570-73

COLONETTE (also colonnette). A small column or baluster.

COLONNADE. A line of columns carrying an entablature.

COLORE. Color or the application of paint or coloring. In the sixteenth century, colore came to refer to a pictorial quality that was contrasted with disegno.

Titian's Danaë

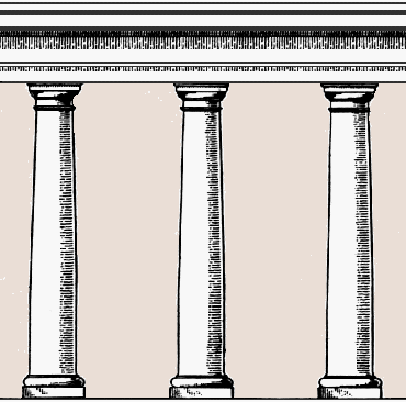

COLUMN. In classical architecture, a cylindrical support consisting of a capital at the top, a shaft in the middle, and a base at the bottom. The base is not present on columns of the Greek Doric order.

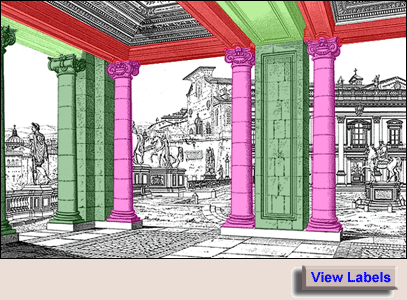

COMPOSITE ORDER. An order developed by the Romans that is distinguished by a capital combining the prominent volutes of the Ionic order with the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian.

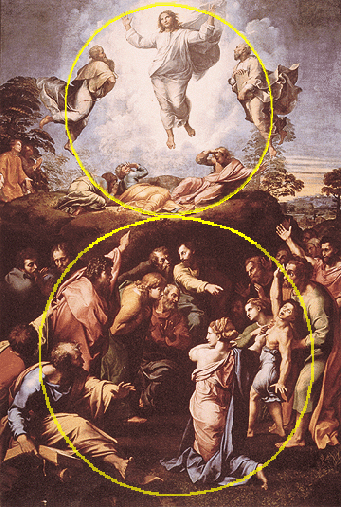

COMPOSITION. Arrangement of parts. In painting, this applies to pictorial elements like line, shape, and color. In architecture, spatial qualities such as the interplay of solids and voids are also involved.

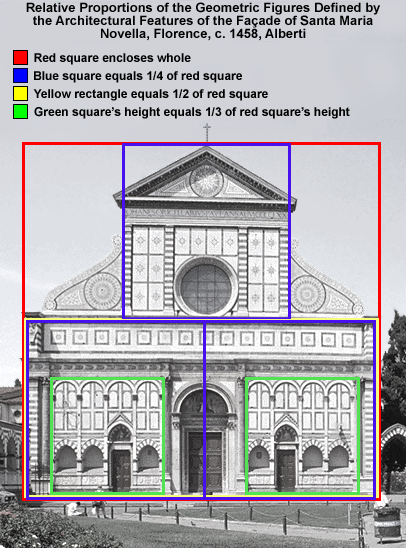

|

Alberti's Square-based composition of Santa Maria Novella |

CONCRETE. Concrete is a mixture of a binding agent called cement, an aggregate, and water, whose presence produces a chemical change in the mixture that transforms it into a rock-hard, continuous mass. In Roman times, the binder was made from lime, and the aggregate was composed of caementa, which consisted of broken rock or small stones, and pozzolana, a sand made from volcanic ash. Pozzolana, which was named for the town of Pozzuol, gave Roman concrete much of its strength and ability to withstand leakage when used in water. By the third century BC, the Romans were using an early form of concrete, but it was not until the second century A.D. that the potential of this material to form curving, shell-like structures was explored. To avoid the staining that made exterior concrete increasingly unattractive over time, buildings were covered by cut stone or a cheaper material like pieces of stone or tile that were pushed into an outer layer of wet mortar. The pieces and their arrangements evolved over the centuries from coarse types like opus incertum to refined treatments like opus reticulatum and opus testaceum.

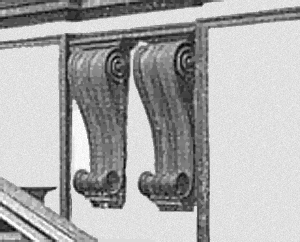

CONSOLE. Bracket in the form of a scroll. Consoles are generally taller than they are deep and have parallel sides and a double-curve in profile. They may be purely decorative or may function as corbels. Michelangelo used consoles to support the lintels of windows for the Palazzo Medici and to suggest support under the columns of the vestibule of the Laurentian Library.

Consoles in vestibule of Michelangelo's Laurentian Library, San Lorenzo, Florence

CONSTRUCTION. In architectural illustration, a representation of a building's interior and structure in which the layers are peeled away selectively to reveal distinguishable interior parts. This presentation, usually a perspective drawing, differs from a section, which reveals the components in the structure only where they are intersected by a single imaginary plane. Perspectives and sections can also be combined to create constructions. Constructions are useful to reveal interiors, simplify structural principles, illustrate parts and their assembly, and separate the distinct stages of complex building procedures.

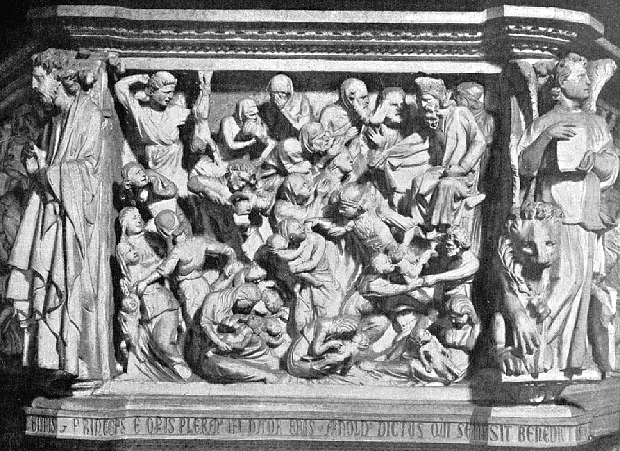

CONTINUOUS NARRATIVE. The depiction of several, related scenes within a single, unified pictorial space. This technique, which was popular in fifteenth-century art, was much used in Roman relief sculpture. An especially impressive Roman example of continuous narrative is the Column of Trajan, a giant column that is encircled by a spiral of episodes illustrating the Emperor Trajan's military campaigns.

Massacio's The Tribute Money, Brancacci Chapel, Sta. Maria del Carmine, c. 1427

Peter is shown in three different scenes: In the center Christ responds to an assessment by the tax-collector by telling Peter that a coin for taxes will be provided from the mouth of a fish. On the left Peter takes the coin from the fish's mouth, and on the right he pays the tax-collector.

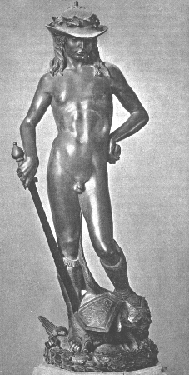

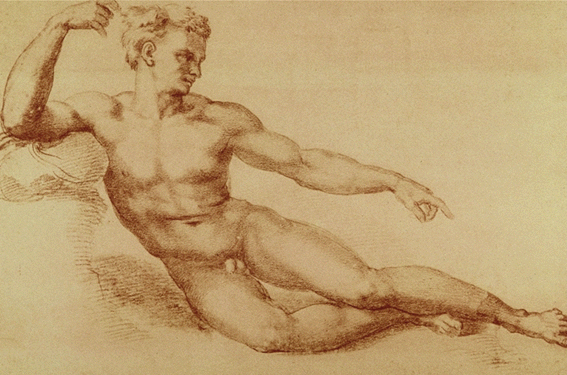

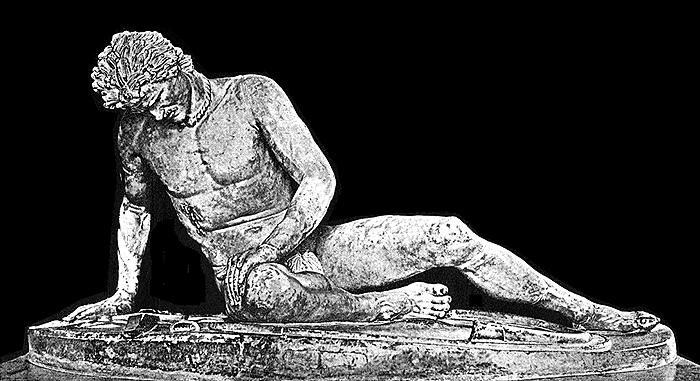

CONTRAPPOSTO (Italian for "set against"). Method of dynamically posing a human figure, which was first used by Greek artists. The parts of the body act in opposition to each other as a result of the figure's weight resting on one leg, causing the corresponding hip and opposite shoulder to rise and creating a slight twist in the torso. Such a presentation of the interaction of the body's parts was important in creating a convincing representation of potential movement.

Use of contrapposto, Donatello's David, 1430 |

Absence of contrapposto, Romanesque figure |

CONVENTION. A widely used and accepted representational mode or device. Conventions range from visual distortions of natural appearances, such as using a smaller scale for trees and buildings than for figures, to communicating narrative content through composition, such as placing a figure at the edge of the picture to indicate that the person had come from far away.

Jacopo Bellini's Madonna of Humility, 1430

The smaller scale of the donor reflects his lessor importance.

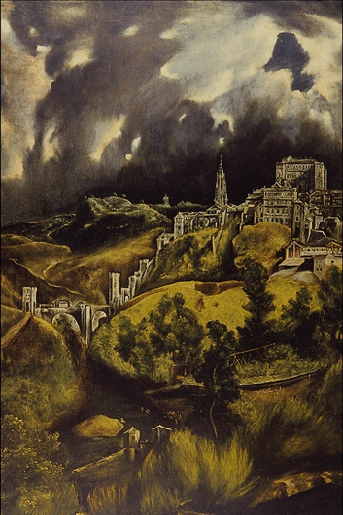

COOL. When used as an adjective for hue, cool refers to the range of colors in the purple-blue-green sector of the color wheel. Gray is often referred to as warm or cool in accordance with its constituent colors. |

El Greco's View of Toledo, c.1597 |

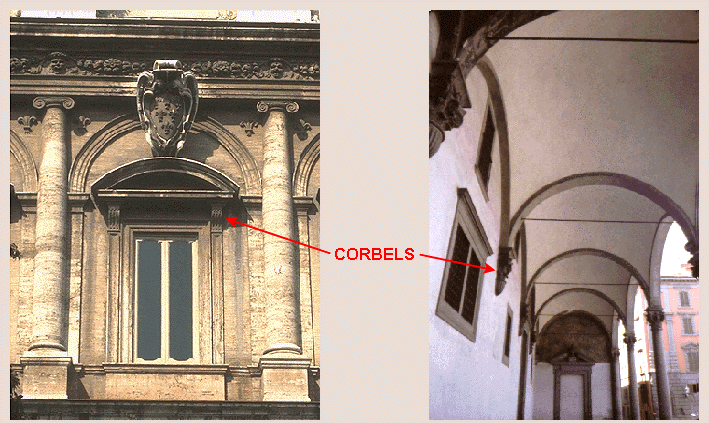

CORBEL. In masonry construction, a projecting stone that can be used to support an end of a horizontal member like a beam, the springing of an arch or vault , or a projecting feature like a balcony. In cornices, the modillions and dentils, function as corbels. Also see corbel arch.

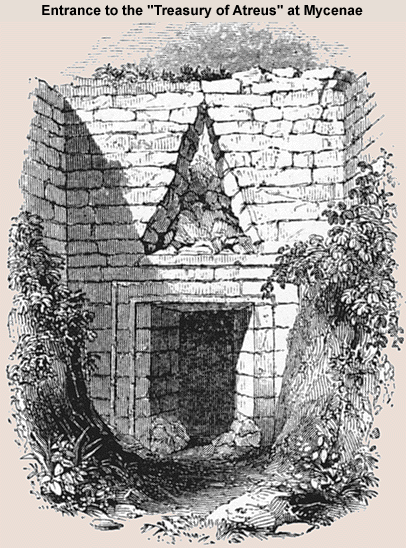

CORBEL ARCH. Arch achieved by stacking stones in such a way that each one extends further inward than the last. This form of arch is based on the cantilever principle in which a projecting member is held in place by a downward force on the other side of its fulcrum (balance point). In masonry construction, this force is created by the stonework above the projecting stone. Sometimes called a "false arch," corbel arches have a limited load-bearing capacity compared with true arches, which are composed of voussoirs.

CORINTHIAN ORDER. Order developed by the Greeks having a more slender column than those of the Doric and Ionic orders, a capital that is carved with rows of acanthus leaves interspersed with small volutes at the top, a shaft that may or may not be fluted, and an entablature that is similar to that of the Ionic order in having a continuous frieze.

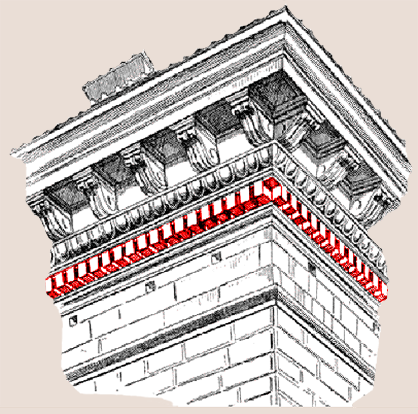

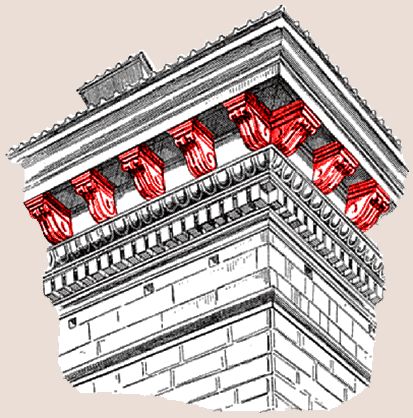

CORNICE. Uppermost section of an entablature. In the construction of a classical temple, the cornice acts as a lip to bridge the gap between the projection of the roof and the front plane of the frieze or upper wall. It is formed by a series of moldings whose projection is supported by corbels in classical forms like modillions and dentils. At the gable ends of the temple, the cornice divides to surround the pediment. (2) Capping feature of a building or non-sheltering structure like a wall or pedestal. The crowning feature of a Renaissance palace is generally called a "cornice" even though its form may be that of a whole entablature.

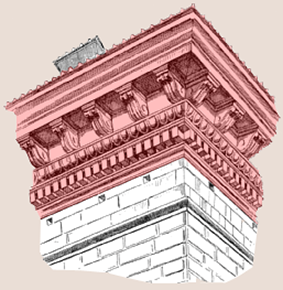

1) Cornice of an entablature, Palazzo Strozzi |

2) Cornice of a building, Palazzo Strozzi |

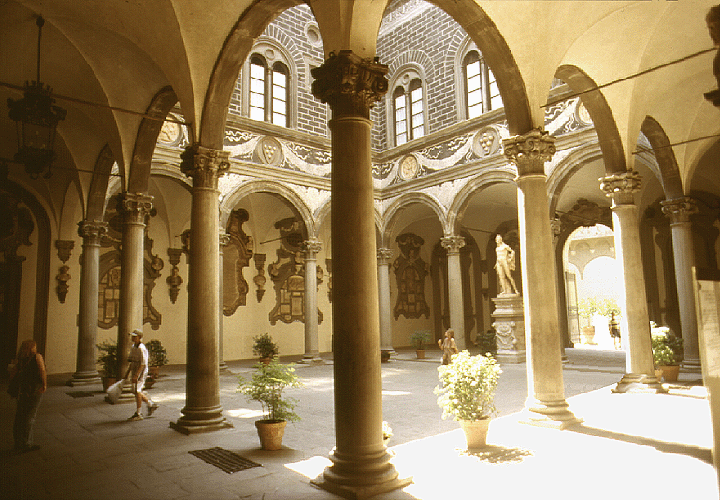

CORTILE (Italian word for "courtyard"). An open-air space within a building. Courtyards provide light and ventilation. Renaissance courtyards were often surrounded by loggias, which functioned as covered hallways.

Michelozzo's Palazzo Medici, begun 1444

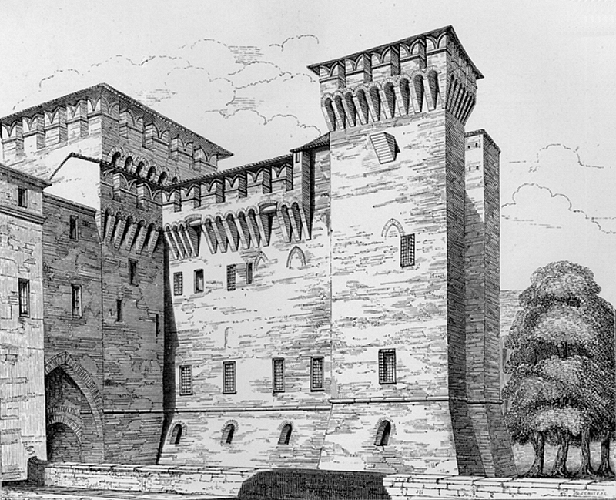

CRENELLATION. Low wall on the edge of a roof or terrace that has a regular series of indentations in alternation with solid wall, which enabled soldiers to alternately shoot and take cover. Also known as a battlement.

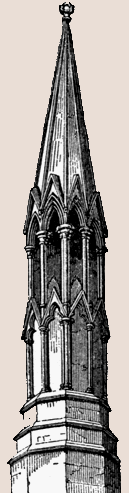

CROCKET. Projecting ornament, generally in a leaf form, that was commonly used in Gothic architecture as a repeating element to form a trim along the edges of gables, pinnacles, spires, and other upward-pointing features.

CROSSING. The area in a church with a cross-shaped plan where the nave and transept intersect.

CROSS VAULT. Vault formed by the intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults of the same size. Also called a groin vault.

CRUCIFIX. Cross-shaped painting or sculpture with a representation of Christ on the cross. Crucifixes vary in size and material, ranging from small, cast-metal neck pendants to large, painted wooden panels that are mounted over altars or carried in processions on religious holidays.

CRYPT. Vaulted area below the main floor of a church that is generally used for burial. Crypts are usually located at the east end.

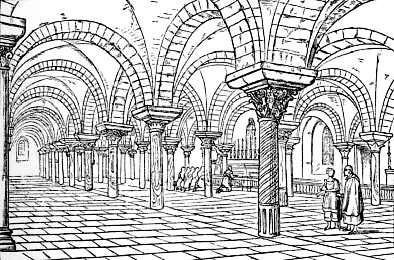

Crypt of San Nicola, Bari |

Section of San Ambrogio, Milan |

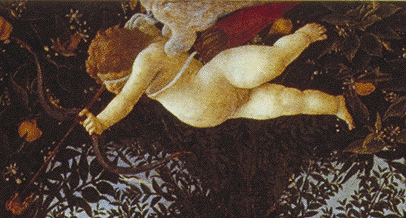

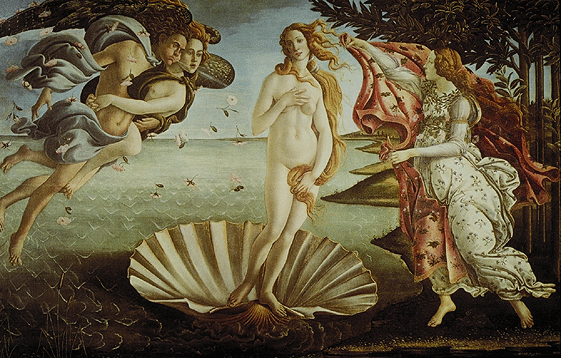

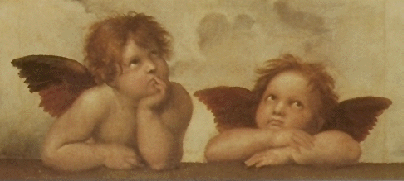

CUPID. Son of the ancient Roman goddess of Love, Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology). Cupid was known as Eros to the Greeks and Amor to the Romans. Like his mother, he was associated with love, and three of his attributes, the bow, arrow, and quiver, refer to the mythical notion that one would be smitten by love if hit by one of his arrows. Cupid often had wings, and sometimes, a blindfold, which is linked with both the notion that love is blind and that some aspects of love are identified with the darkness of sin. In the Renaissance, Cupid evolved into baby angels known as putti.

Detail from Botticelli’s Primavera, 1482

![]()

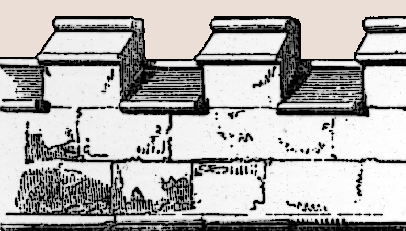

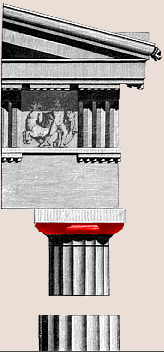

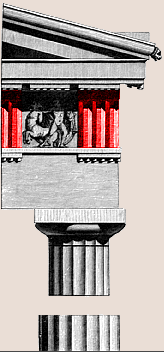

DENTIL. A block-shaped projection that is used in a series to support one of the moldings of a cornice. The name "dentil" reflects their resemblance to teeth when used in a series.

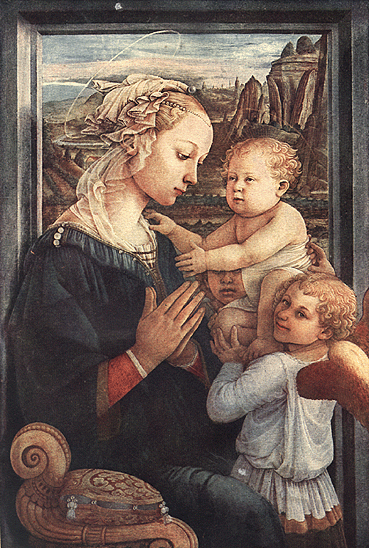

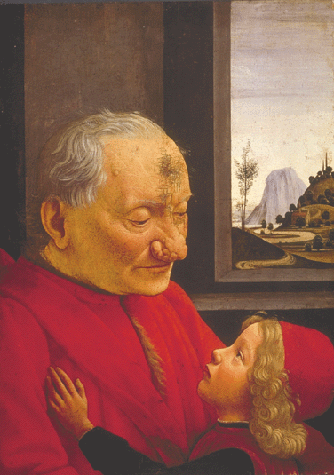

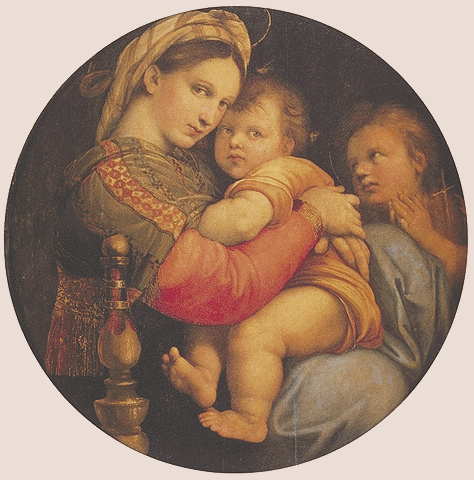

DEVOTIONAL PIECE. Non-narrative subject intended as an image for religious meditation, such as an icon. In the Renaissance, devotional pieces often made holy personages seem more human and less remote.

Fra Filippo Lippi's Madonna and Child with Angels, c. 1455

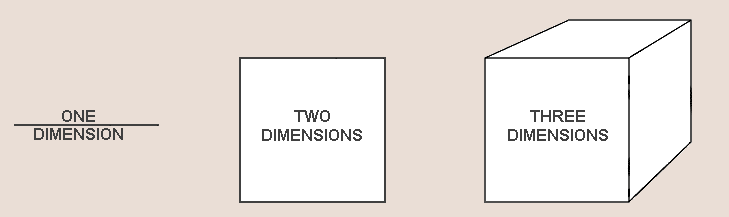

DIMENSION. Measure of extent. A point (the intersection of two lines) has no dimension, and a line has one dimension. "Two-dimensional" refers to having length and width, like a plane. "Three-dimensional" refers to having depth in addition to length and width. (In physics, the fourth dimension is time.)

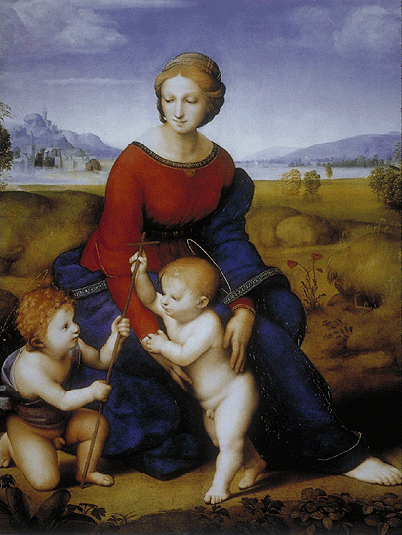

DISEGNO (Related to the Italian word disegnare, to draw). The term disegno, which was often used in Florentine Renaissance art theory, usually meant both drawing and design simultaneously. A drawing was considered to embody the design or organizational principle of the finished work derived from it. Drawing was less important to sixteenth-century Venetian artists, who preferred to paint directly on the canvas with little underdrawing and few preparatory sketches. Their techniques (as opposed to those of the more meticulous Florentines) are often described as being based on colore, the application of paint or coloring. The relative merits of Venetian colore and Florentine disegno were much debated in the sixteenth century and later.

Raphael's Madonna of the Meadow, 1505

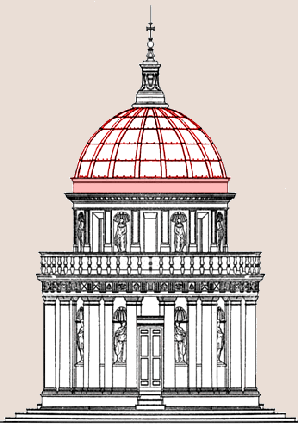

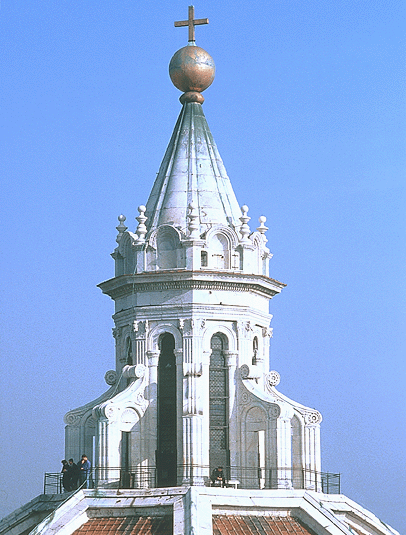

DOME. A rounded vault based on a circular, elliptical, or polygonal plan. In the Renaissance, domes were elevated on drums and topped with lanterns. Pendentives transferred the weight to four massive piers. Renaissance domes were often radially ribbed or coffered. Because domes signified Heaven, their interiors were often painted with gold stars against a blue background, but toward the end of the Renaissance, illusionistic paintings of figures in Heaven became popular. The contours of domes ranged from shallow to steeper than hemispherical. Domical vaults, sail domes, and parachute domes (also called "pumpkin" or "melon" domes) are variants of the dome. A size comparison of world monuments demonstrates the achievement of very large domes by ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Renaissance architects.

Bramante's Tempietto, designed c. 1502

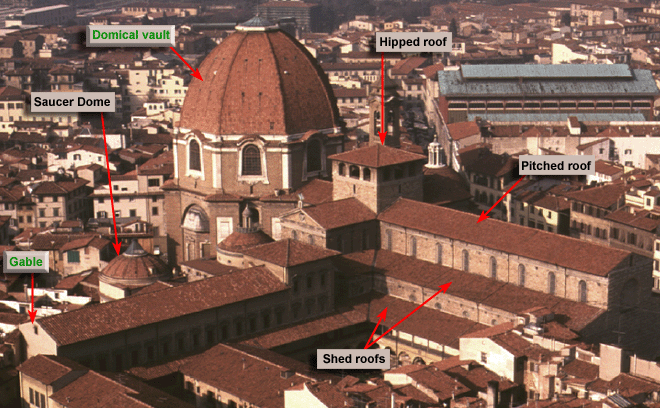

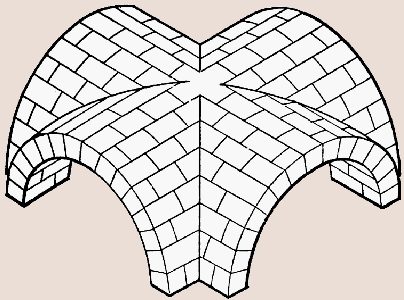

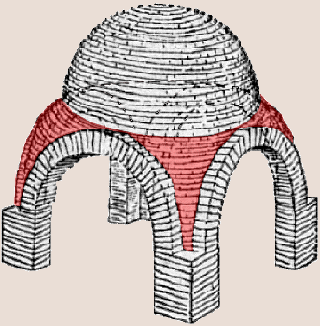

DOMICAL VAULT. Also called a cloister vault, a dome that rises from a square or polygonal base and is formed of a series of wedge-shaped units that are separated by groins or ribs. These units, called cells or webs, are straight in plan (not curving from side to side) and curved in section (curving from apex to base).

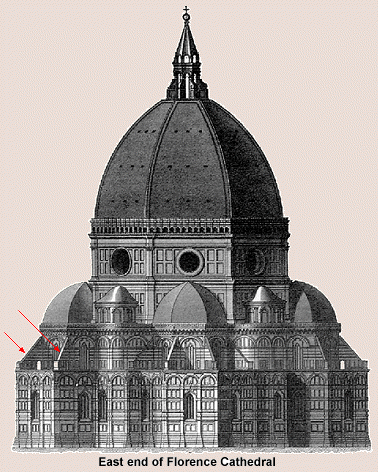

Brunelleschi's Dome of Florence Cathedral, 1420-36

DONOR. Person or group who commissions a public work such as an altarpiece for a church or a sculpture for a piazza. In the Renaissance, members of wealthy families and officials of the church, especially popes and cardinals, commissioned buildings and art works for churches, which often granted them space for private chapels. The contributions of donors was generally advertised on buildings by inscriptions and family crests. Art works like altarpieces and fresco cycles in churches sometimes included portraits of the donor family. They might be pictured as participants in narrative scenes or kneeling figures in devotional paintings. Reference to patronage is sometimes symbolic as in the inclusion of acorns and trees in commissions by the Rovere family, whose name means "oak".

Detail of Titian's Madonna of the Pesaro Family, 1519-26

In addition to including the donor's family, there is a reference to a family-related event: The presence of an armored figure raising the Pesaro-family banner and leading a Turkish captive refers to the victory of Bishop Jacopo Pesaro (who kneels before the Virgin and Saints Peter and Francis) over the Turks at the Battle of Santa Maura.

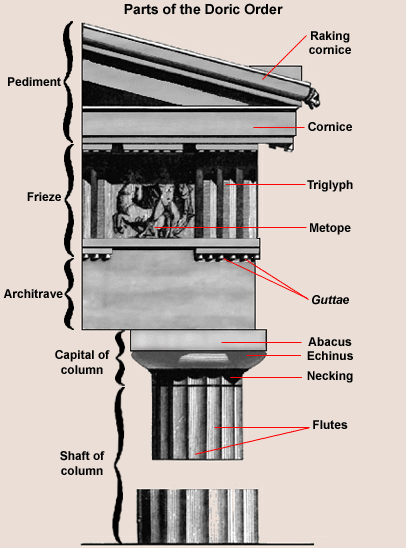

DORIC ORDER. The earliest of the architectural orders invented by the ancient Greeks. The column shaft is tapered upward and fluted with vertical grooves whose borders form a series of pointed edges. In the original Greek version, the column's lower edge rests directly on the floor without a base, but post-Greek versions do have bases. The flutes are continued upward into the necking, the lowest of the capital's three horizontal members. Above the necking is a circular form called the echinus, which carries a square cap called the abacus. The columns support an entablature whose frieze consists of alternating triglyphs and metopes. Many scholars interpret the triglyphs as vestigial remains of three-plank beams used in building early wooden temples. In the evolution of Greek architecture, earlier examples of the Doric order differed from later examples in having wider capitals, more pronounced entasis, and more massive proportions.

DOVECOTE. Enclosure for pigeons that includes holes through which the birds can come and go and perches on which they can roost. Dovecotes are generally placed in elevated locations.

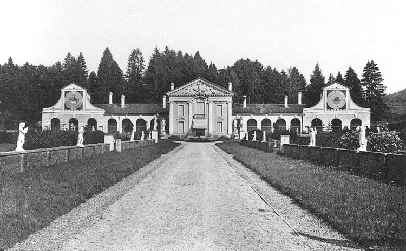

Dovecotes occupy the upper story of the outer blocks of Palladio's Villa Barbaro at Maser.

DRAWING. Image made by making lines on a prepared surface. In the Renaissance, drawings were made in several media: charcoal, chalk, pen and ink, wash, metal point, and combinations of these. Different types of drawings served different purposes. The basic types were sketches, studies, and presentation drawings. Studies could be further divided as preliminary (or preparatory) drawings, detail drawings, and process drawings.

Raphael's Death of Adonis

DRESSED STONE. Stone that has been prepared for construction by cutting into blocks or slabs and finishing the outer surfaces, which are usually smooth.

Smooth-faced stone Rock-faced stone

DRUM. Cylindrical, polygonal, or square wall supporting a dome. 2. One of the cylindrical blocks of stone that form the shaft of a column. The joints between drums are readily seen at many ancient temples.

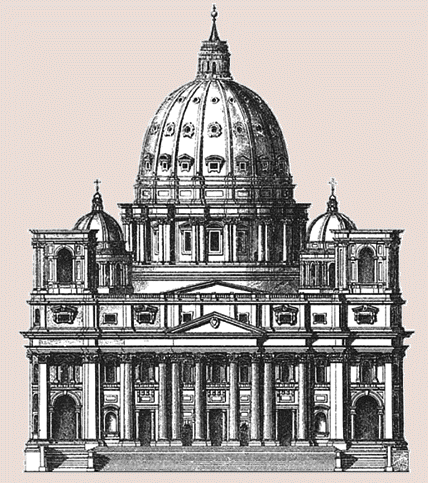

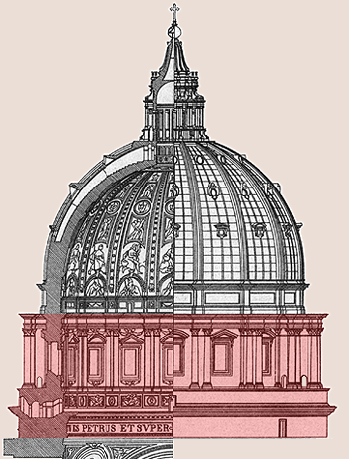

Section and elevation of St. Peter's, Rome

![]()

EAST END. The end of a church containing an apse, regardless of its actual orientation. Because the east has special significance in Christianity as the location of Eden and the Holy Land and the direction where the sun is re-born each morning, this end usually contains the altar, where the Sacrament of the Eucharist is performed.

ECHINUS. Convex molding of a Doric capital that is located between the necking at the bottom and the abacus at the top. The echinus' curved plane gives it a cushion-like appearance.

ELEVATION. Presentation of a vertical facing of a building or part of one as if its features were projected at a perpendicular angle onto a vertical plane that is parallel to the building. An elevation is a form of orthographic projection, which lacks the illusion of depth present in a perspective rendering. Elevations can be rendered with shading to give the illusion of depth while maintaining the accurate proportions found in orthographic projections.

In this elevation of St. Peter's, which includes towers that were not built, the dome appears to be roughly twice the height of the façade, whereas in a photograph, it appears much lower due to the effects of perspective.

|

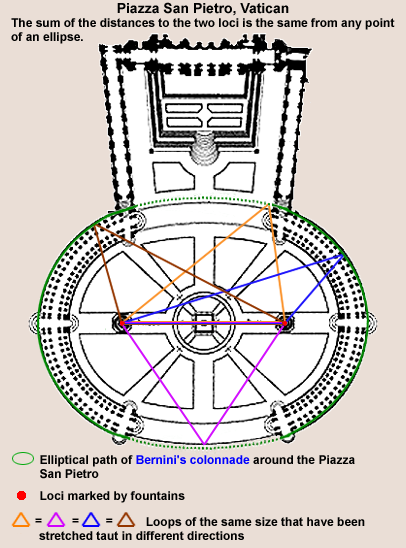

ELLIPSE. An ellipse is a closed curve based on a conic section. Although the category of ellipse includes the circle, which is a conic section that has been taken at a perpendicular angle to the cone's axis, the term usually refers to sections that have been taken at oblique angles. Such curves are regular, symmetrical, and have two centers, which are called loci. The sum of the lines to the two centers from any point along its course is equal to the sum of the lines to the centers from any other point. This can be visualized by a simple mechanical process for creating an ellipse in which pins are fixed to two points, and a loop with slack is placed around them. The continuous curve that can be drawn by moving a pencil along the outer limit permitted by the loop is an ellipse. Ellipses vary in shape from wide to circular, depending on the distance between the loci in comparison with the ellipse's size. The smaller the difference (or the tighter the loop), the wider the shape. Ellipses were first used in Renaissance architectural design in the second half of the sixteenth century by Michelangelo at the Campidoglio, by Ligorio at the Casino of Pius IV, and by Vignola at Sant' Andrea in the Via Flaminia. In the seventeenth century, ellipses replaced circles as the basis for many plans and sections.

EMBRASURE. An opening through a wall or parapet that is tapered to provide protection to the soldiers firing a cannon through it. Angling embrasures obliquely increased their effectiveness in providing cover but restricted the gun's range. Although the openings were usually largest on the inside, placing the embrasure's narrowest point, which was the barrel's pivot point, toward the interior increased the gun's range. Variations include the vertical "keyhole" and the horizontal "letterbox."

Embrasure in vaulting of the upper casemate of the bastion at Porta San Viene

(Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Adams)

ENFILADE DOORS. Interior doorways that are aligned with each other so that when the doors are open, one can see through a series of rooms. In connecting a line of rooms, the doors are often located next to exterior walls. When privacy from this open corridor was needed, screens or hangings were used. (A closed corridor would have blocked the windows.) In the sixteenth century, enfilade doorways came to be used in palaces like the Palazzo Farnese and villas like Palladio's Villa Barbaro, and by the seventeenth century, enfilade openings were a standard feature.

View from the Sala d' Costantino through the other rooms of the Raphael Stanze

ENGAGED COLUMN. Column embedded in a wall, or more commonly, cut to have a flat side that is applied to a wall while giving the appearance of being embedded.

Detail of Theater of Marcellus, Rome, c. 23-13 BC

ENGRAVING. Print made from a metal plate (usually copper) that has been incised with a burin, a tool that makes a V-shaped groove. A reversed image is printed by applying ink to the plate, wiping it off the surface but not out of the grooves, and pressing a damp piece of paper against the plate so hard that the paper penetrates the grooves and picks up the ink.

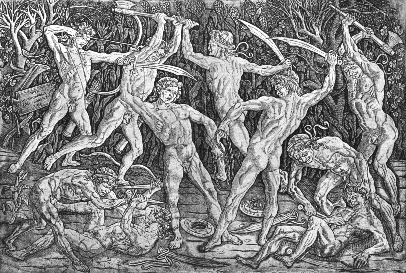

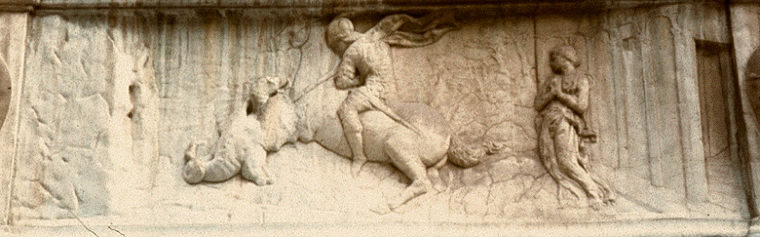

Pollaiuolo's Battle of the Ten Nudes, 1465

ENTABLATURE. The horizontal structure above the columns, composed of three horizontal members: architrave, frieze, and cornice. In the construction of a Classical temple, the entablature transfers the weight of the roof to the columns or walls below. The ornamentation of the entablature varies according to the individual order.

ENTASIS. A slight outward curve in the shape of a column, which is intended to counteract the optical illusion of dished-in sides created by straight-sided columns.

First Temple of Hera, Paestum, Italy, c. 550

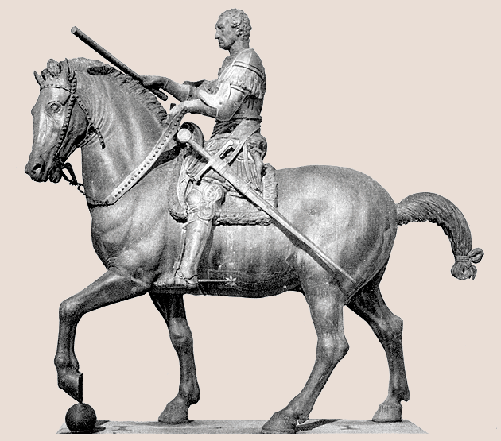

EQUESTRIAN. Related to horseback riding. In art, an equestrian work is usually a portrait of a person mounted on a horse. The Romans cast bronze equestrian portraits of their emperors for public monuments, but only the Marcus Aurelius has survived to the Renaissance. In the Renaissance, bronze equestrian statues honored condottieri and rulers. Painted equestrian representations included tomb frescoes, formal portraits, and multi-figure scenes.

Donatello's Gattamelata, 1445-53

ESPLANADE. Level, open area, often near a body of water, that has been made suitable for walking by paving or landscaping.

Vignola's Orti Farnesiani, Rome, c. 1570-73

ETCHING. Print made from a metal plate whose image was created by burning with acid. The typical metal used is copper, although some of the earliest examples were executed using iron. After an acid-resistant wax or resin has been applied to the surface of the plate, a burin is used to scratch in the design, exposing the metal plate below. The plate is then bathed in acid, which etches, or "bites", the exposed areas, which during the printing process transfer ink to the paper. German armor manufacturers invented the process in the fifteenth century, and painters and printmakers soon began experimenting with the technique. In the early sixteenth century, the Swiss artist Urs Graf and the German artists Hans Burkmair and Albrecht Dürer all produced etchings. Parmigianino was the first, and perhaps the most important Italian Renaissance artist to use the technique. In a few examples, he combined etching and woodcut to create a more painterly effect, a technique emulated by Federico Barocci, a painter from the Marches. |

Etching of Bramante's Tempietto in Rome |

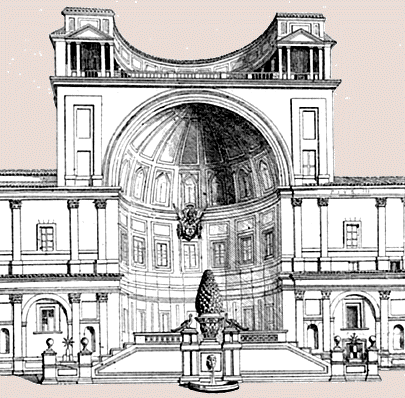

EXEDRA. Semicircular structure that is usually part of another structure, like an apse, a porch, or a section of a colonnade.

Ligorio's Nicchione of Belvedere Court, Vatican

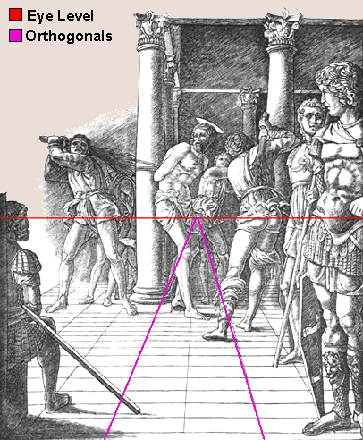

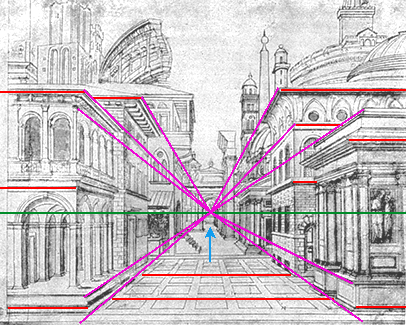

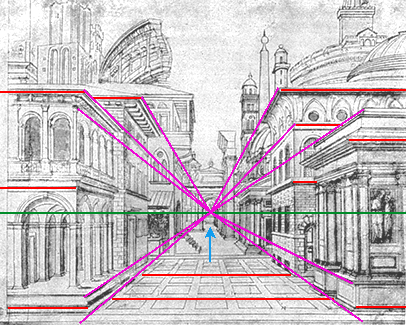

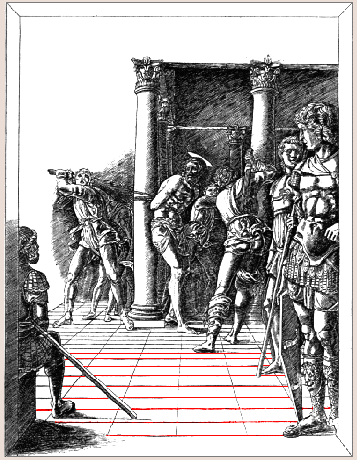

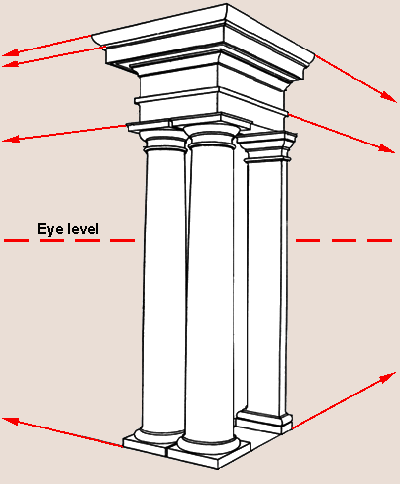

EYE LEVEL. Horizontal line through the vanishing point in a picture made using linear perspective. Also called the "horizon line."

Mantegna's Flagellation of Christ

For dramatic effect, Mantegna has placed the eye level at that of King Herod, who ordered the whipping and observes the scene from the left foreground.

![]()

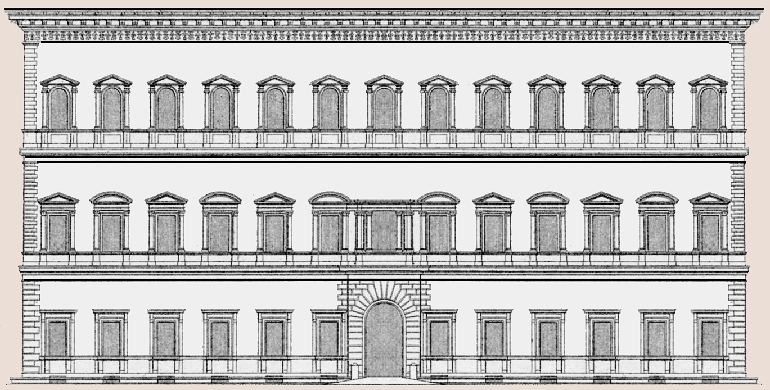

FAÇADE. A face of a building, usually the front. Facciata is the Italian word for façade. The term generally refers to the decorative treatment added to a blank entrance wall.

Alberti's Façade of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, c. 1458-70

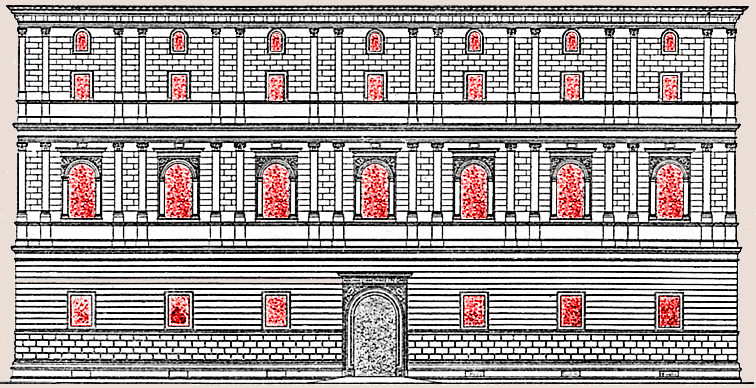

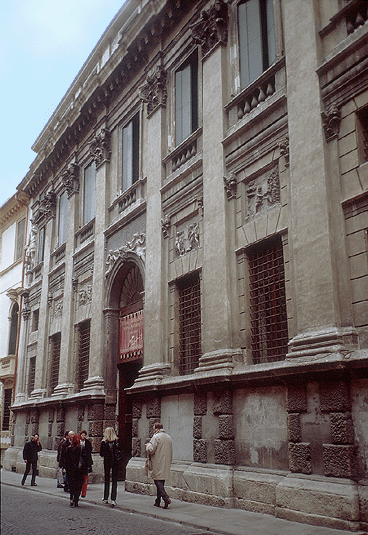

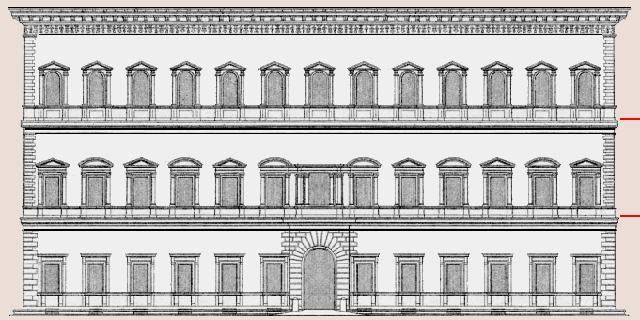

FENESTRATION. The arrangement of windows on a façade. The regularity of the fenestration in the fifteenth century was often compromised by stairways and the positions of the rooms, but in the sixteenth century, regularity was generally a priority.

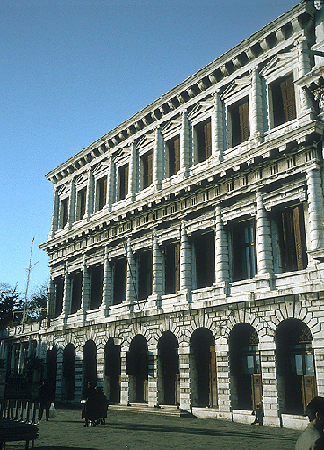

Palazzo Corneto, Rome (later called Palazzo Giraud-Torlonia)

FIGURA SERPENTINATA. Term that refers to a figure whose pose is twisted so that the upper and lower body face in different directions. This posture is especially identified with the paintings and sculptures of Michelangelo and other Italian Mannerists. The term was first used by the Milanese art theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo (1538-92).

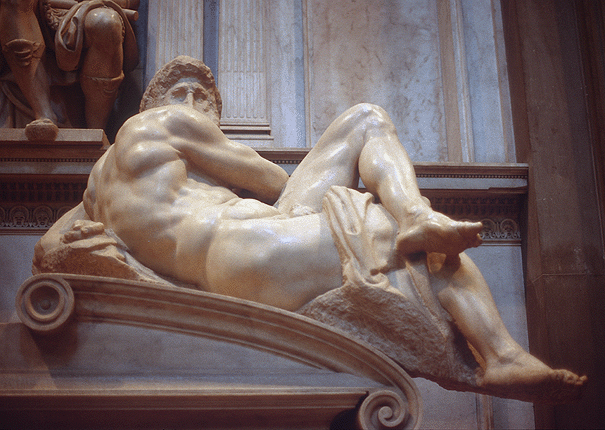

Michelangelo's Night, Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici, Florence, 1524-34

FLUTED. Carved with a series of vertical grooves, as on a column. The flutes of the Doric order touch each other and form pointed edges, but the flutes of the other orders are separated by narrow fillets.

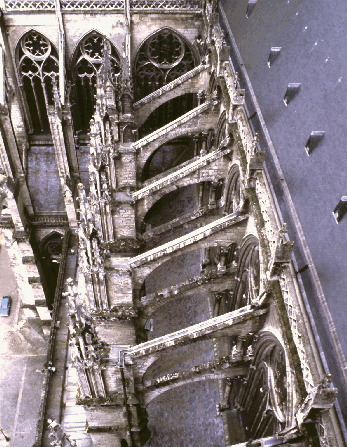

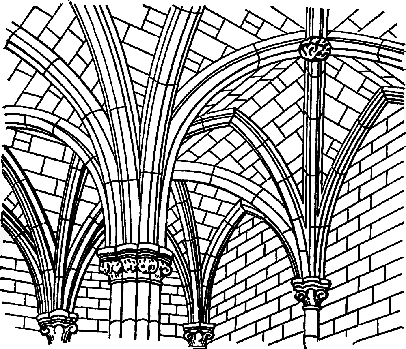

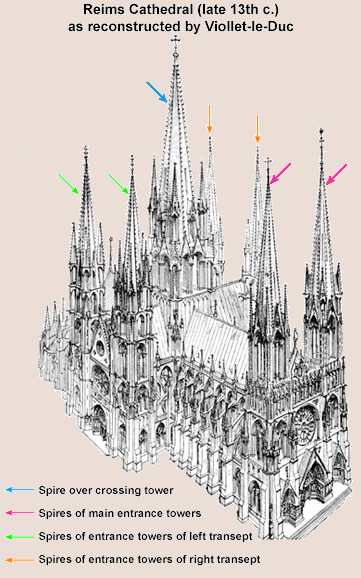

FLYING BUTTRESSES. Buttress in the form of an arch that braces the upper part of a structure against a pier that is some distance outward from the point being braced. In the construction of Gothic basilicas, flying buttresses often extended over the side-aisle roofs from the upper nave walls to piers in the outer walls.

Amiens Cathedral, France, 13th century

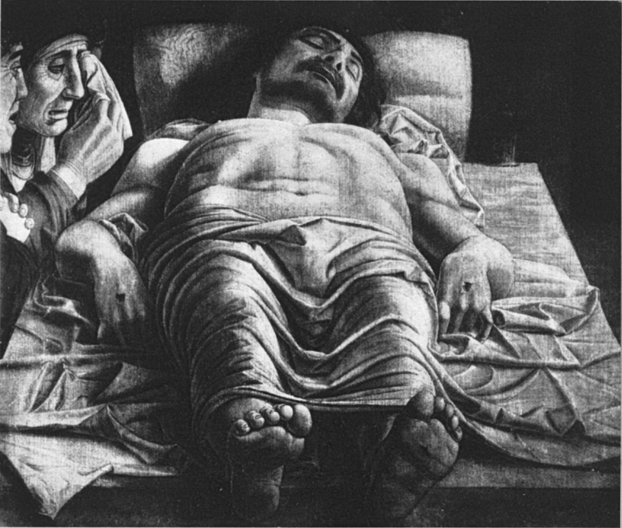

FORESHORTENING. The rendering of an object that extends away from the picture plane so that the object is shortened and parts that are further back appear smaller, thereby creating the illusion of spatial recession.

Mantegna's Dead Christ

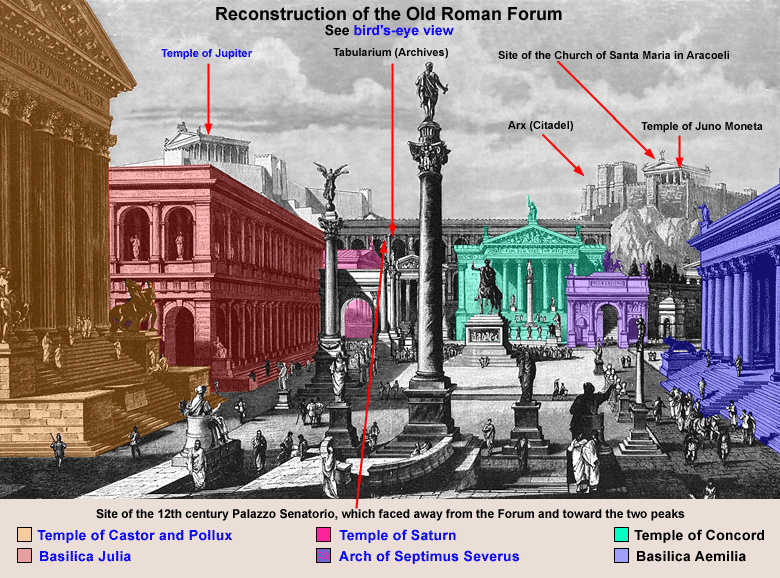

FORUM. A public square that functioned as a marketplace and a site for public ceremonies in ancient Roman cities. The forum was usually located at or near the intersection of the city's two mains streets. Among the types of buildings included are basilicas, temples, triumphal arches, monumental columns, libraries, and markets. The buildings of early forums (or fora) were often added individually over time, but those of later forums were built as unified, symmetrical arrangements of major buildings and peristyle courts. Roman forums exemplified the Roman talent for using architecture to organize large, public spaces in a manner that proclaimed the grandeur of the State.

See Labeled reconstruction of the Forum Romanum

The Forum Romanum, Rome's oldest forum, was crowded with buildings and monuments.

FRESCO. Painting executed on plaster, which may be wet, as in buon fresco, or dry, as in fresco a secco. Although fresco was primarily used to decorate interior walls and ceilings, it was also used for exteriors. Due to exposure to the elements, few of these have survived.

Detail from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, 1508-12

FRESCO CYCLE. Series of fresco scenes on a single theme.

Scenes from Giotto's fresco cycle illustrating Christ's life, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305-6

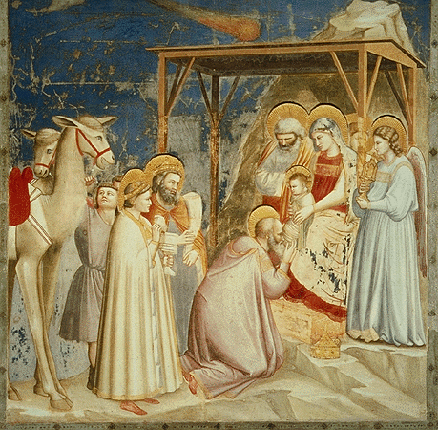

FRESCO A SECCO (Italian words for "fresh" and "dry"). Painting executed on dry plaster. Corrections, details, and certain colors were added at the end. Also called secco fresco.

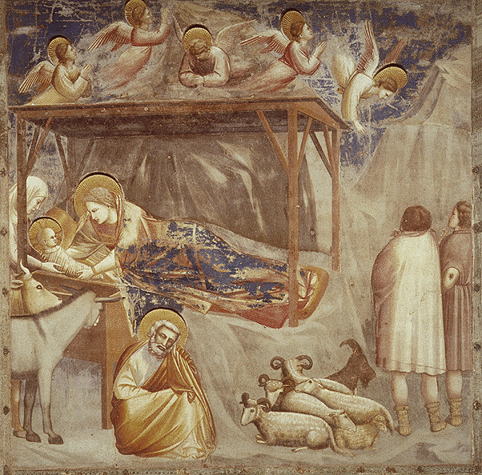

Giotto's Nativity, Arena Chapel, Padua, 1305-6

Much of the blue color of Mary's robes and the sky, which were applied over the dried buon fresco, has peeled off Giotto's painting.

FRIEZE. The central member of the entablature, which is located between the cornice and architrave. In Classical construction, the frieze originally hid the ends of the roof beams. Ancient friezes of the Doric order consisted of metopes and triglyphs, and friezes of the other orders were either plain or carved in relief. Popular subjects included processions and repeating patterns such as festoons and bucrania, vestiges of the harvested produce and animal heads that were once attached to the temple as offerings to the gods. In the Renaissance, ornamented friezes, especially those on domestic palaces, often depicted patterns made up of family emblems and decorative forms such as putti holding garlands. Materials for friezes, which varied regionally, included relief-carved stone, molded terracotta, glazed terracotta, painted stucco, sgraffito, and fresco. The term "frieze" also applies to any continuous horizontal band of decoration, regardless of whether other elements of an entablature are present.

![]()

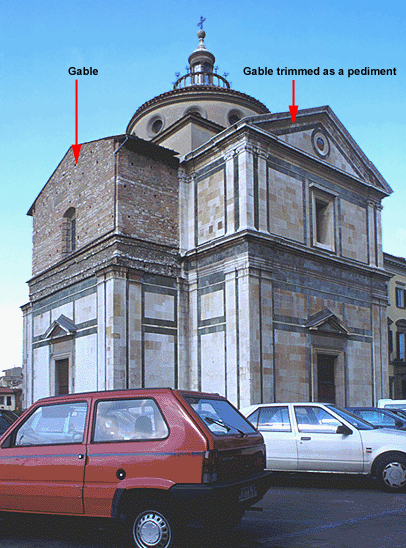

GABLE. Wall area at the end of a pitched roof. Italian Renaissance gables were most commonly associated with the façades of basilicas and were generally detailed as pediments, the shallow-pitched gables used on the ends of Classical temples. The gables of Italian-Gothic church façades generally extended upward past the roof whereas Renaissance gables were generally contained by a cornice along the roof edge. |

Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato |

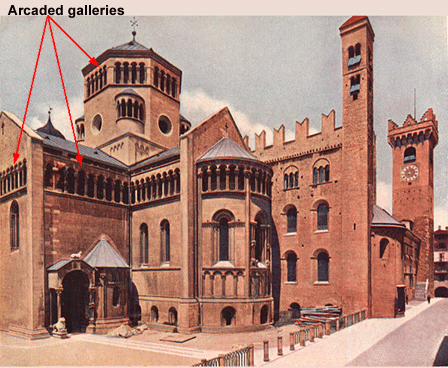

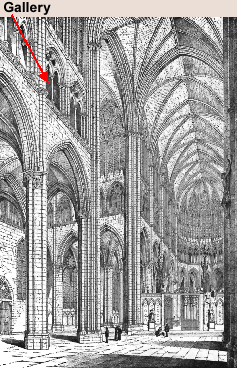

GALLERY. Long passageway or balcony. In medieval churches, the "triforium gallery" was a narrow arcaded aisle above the side aisle. The term has also been identified with long, enclosed passageways. Because these long rooms came to be decorated by paintings, the name "gallery" came to mean a space where art is displayed.

Trent Cathedral |

Amiens Cathedral |

GENRE. Type of picture representing scenes of everyday life. Genre scenes such as men farming and women carrying water date back to Egyptian tomb painting of the third millennium BC After the Greco-Roman era, religious and historical subjects predominated, and it was not until the advent of seventeenth-century Dutch painting that genre again flourished. Genre painting was little practiced in Renaissance Italy except in sixteenth-century Venice. |

Vittore Carpaccio's Two Courtesans, c.1510 |

GESSO. Compound of plaster or gypsum (a white mineral) mixed with glue and ground chalk for use as a primer to form a ground for painting on a rigid support such as a wooden panel.

GIANT ORDER (also called COLOSSAL ORDER). Classification of column or pilaster denoting a multi-story height. Because size is its distinguishing feature, the designation as an "order" is not really in parity with the other orders, which are distinguished from one another by design. Although ancient temples and public buildings often had building-high orders, they were not used in combination with vertically arranged windows or other explicit references to distinct stories. The first architect to use the giant order was Alberti, who used it at both San Sebastiano and Sant' Andrea, where he also incorporated a secondary system of the orders. In the 16th century, the giant order was used by Michelangelo and Palladio, and the latter also expanded the secondary system to include its own pediment. During the Baroque period in the next century, the use of giant order columns and pilasters became widespread.

Usage of Giant Order by Leading Architects

Alberti's Introduction of the Giant Order

Bramante's Use of the Giant Order

Michelangelo's Use of the Giant Order

Palladio's Use of the Giant Order

Alberti's San Andrea, begun 1472

GILDING. Applying a thin layer of gold to the surface of an object. In the Renaissance, gold leaf was applied over an undercoat of bole, a red clay whose color shows through slightly to give the gilded area a warmer cast. Burnishing the leaf produces a shiny surface. (Other metals such as silver or platinum can be similarly applied. Because silver becomes dark with tarnish over the years, its presence is often difficult to see.)

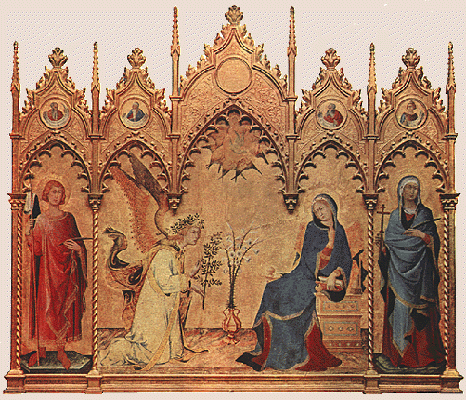

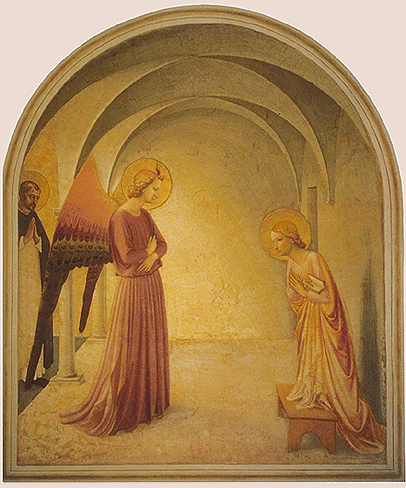

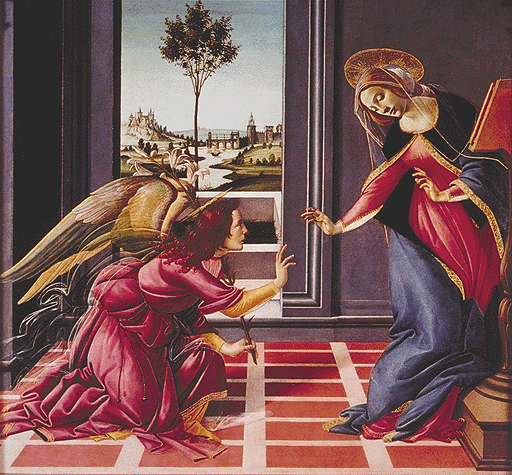

Simone Martini's Annunciation, 1333

GIORNATA (plural = giornate). The patch of intonaco in a fresco that is painted in a single day. The term is derived from giorno, the Italian word for "day"). Because the paint was applied to the intonaco while it was wet, the painter only put on as much of it as he anticipated completing in a single day. Close inspection of the fresco surface can reveal the divisions of the painting into separate giornate, whose edges generally followed the outlines of forms because it was difficult to match colors from one session to another.

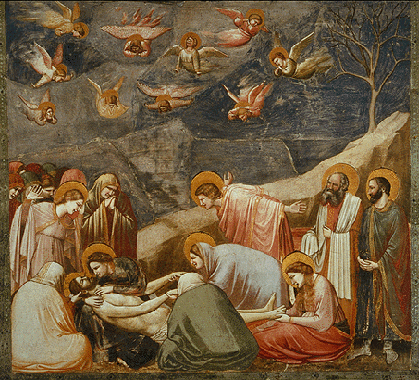

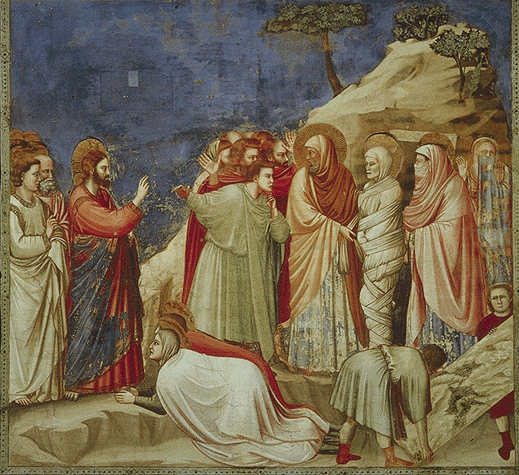

Giotto's Lamentation, 1305-6

The edges of the giornate can be seen in the sky area.

GLAZING. In architecture, the use of glass. In painting, the achievement of color through the application of multiple layers of glaze, a thin, translucent paint made by increasing the proportion of oil to pigment. The special brightness produced by glazing resulted from the oil's transparency, which allowed light to penetrate below the surface into the paint layers, where it could be reflected by individual particles of pigment.

Titian's Venus and the Lute Player, 1560

GOLDEN SECTION (also called GOLDEN RATIO and GOLDEN MEAN). Proportion of two dimensions in which the ratio of the smaller one to the larger is the same as the ratio of the larger one to the total of both. In Greek, this particular relationship is called phi. Numerically, this proportion is roughly 3:5. The total of 3 + 5 is 8, and the ratio of 5:8 is roughly equivalent to 3:5.

![]()

Painters and sculptors used the Golden Section to determine many proportions, and architects used it to determine the dimensions of rooms. Some Renaissance theorists, such as Luca Pacioli, considered it divine.

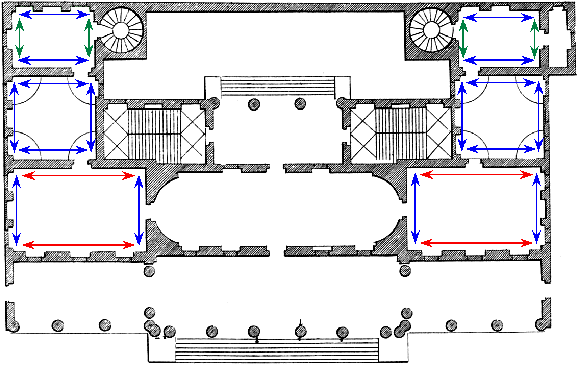

Plan, Palladio's Palazzo Chiericati, Vicenza. begun c.1547

The colors indicate corresponding wall dimensions. The short sides of the large rectangular rooms (blue arrows) are the same dimension as the long sides of the small rectangular rooms. Proportions that roughly approximate those of the golden section are formed by the length and width of the rectangular rooms and by the lengths of the large and small rectangular rooms.

GOLD LEAF. Tissue-thin sheets of gold made for use in gilding by pounding pieces of gold with a hammer. 2) A golden surface that is achieved by the application of gold leaves.

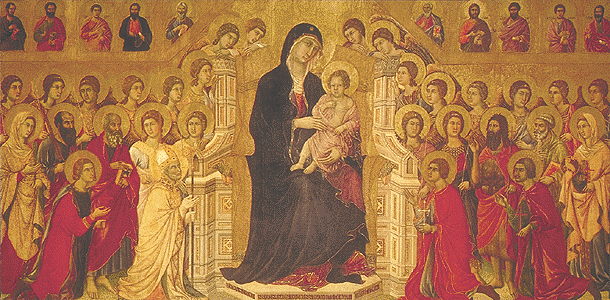

Duccio's Madonna and Child

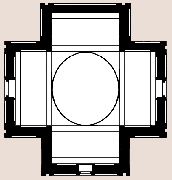

GREEK CROSS. Cross having four arms of equal length.

Plan of Giulio da Sangallo's Santa Maria delle Carceri, begun 1485

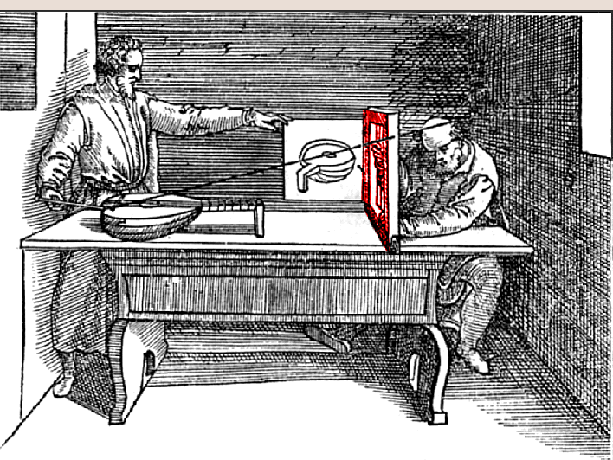

GRID. Set of horizontal and vertical lines laid over an image that is commonly used as an aid for enlarging preliminary drawings or making drawings from a three-dimensional models. This procedure is generally accomplished through the following steps:

1) If the original is a drawing, lines are simply added; if the original is a three-dimensional form, a grid is constructed by attaching wire or string to a frame positioned between the subject and artist, who must maintain a fixed position.

2) A grid of the same number and configuration of lines is drawn onto the surface to be painted.

3) The artist copies the forms of the preliminary drawing so that their sizes and placement on the new grid correspond to those on the grid of the preliminary drawing.

Tintoretto's Study of a Wedding Figure

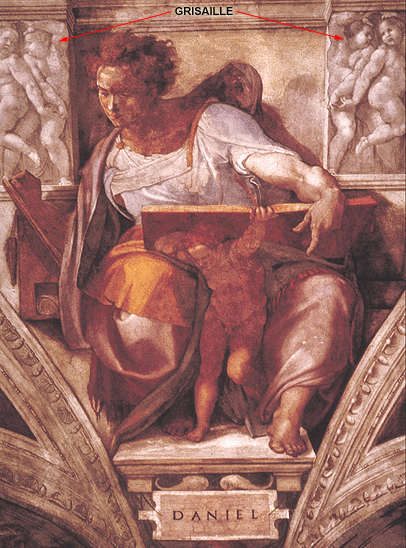

GRISAILLE. From gris, the French word for "gray.") Painting executed in different values of the same color, usually gray. "Grisaille" is derived from gris, the French word for "gray." Such paintings were used as preparatory studies for full-color paintings, as underpaintings, or as finished works imitating sculpture. Grisaille was commonly employed for frescoes decorating palace façades.

Michelangelo's The Prophet Daniel on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Vatican, 1508-12

GROIN. An edge of the intersection of two vaults.

GROIN VAULT. Vault formed by the intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults of the same size. Also called a cross vault.

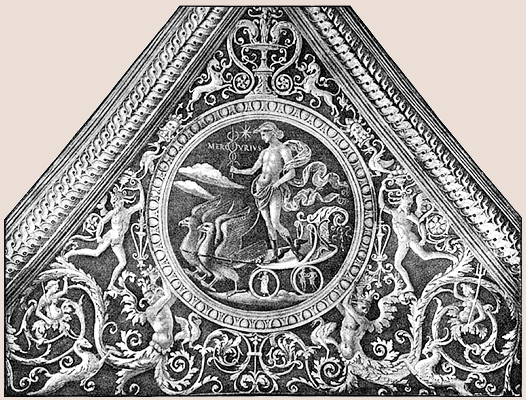

GROTESQUE. Fanciful ornamental designs from antiquity that integrated arabesques with human, animal, and plant forms. Such designs were first known in the Renaissance from the Domus Aurea, which was excavated in the late-fifteenth century. Raphael and his circle popularized the grotesque's use for painted and stuccoed decoration. The name "grotesque," which is derived from grotta ("cave"), refers to the underground location of the Domus Aurea, which had been covered over after Nero's time.

Ceiling of the Raphael's Villa Madama, Rome

GROTTO. Artificial cave-like structure (grotta means "cave"). Grottoes are usually embedded in garden walls or nestled in hillsides. Sometimes they are attached to the exterior walls of houses. Although they were intended to imitate natural cavities like those found on the islands of southern Italy, they often contained elaborate sculpture, often of sea creatures.

Grotto of the Animals at the Villa Medici, Castello

GROUND. Layer of material that is applied to a support before painting to improve adhesion and prevent the paint from being absorbed. The ground varies with the support: gesso is used for panel painting, intonaco for fresco, and size (a dilute solution of glue or resin that remains flexible when dry) for canvas.

GUILD. An association of tradesmen--merchants, artists, craftsmen--formed in order to promote the mutual well-being of the group. They regulated the production and training of their members, thus ensuring standards of conduct and quality. Membership in a guild was essential for securing commissions. For political reasons, most guilds were associated with individual cities. In some cities, like Florence, guilds participated in local government, and wealthier guilds, like those of bankers and wool merchants, held more power than lesser ones like that of the workers in stone and wood. They often functioned as or were linked to religious confraternities. In this capacity they held devotional services to a Patron Saint, and at times, they were major art patrons. Guilds were very powerful in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but their membership waned as production and markets increased in scale. To some small degree, both modern labor unions and government regulatory commissions are heirs to the guild system.

Nanni di Banco's relief at the base of a niche on Orsanmichele sponsored by the guild of workers in stone and wood

![]()

HATCHING. Network of parallel lines or criss-crossed parallel lines (cross-hatching) that simulate shading and contour in drawings executed in a linear medium like pen and ink.

Raphael's Study for Madonna and Child with John the Baptist

HERM. Pillar or support consisting of a male head or head and shoulders that becomes a downward tapering, square-in-section pedestal. Herms are a type of "term" or "terminal figure," which often includes the torso as well as the head and shoulders. Terms can be either a male or female. Both forms, which are derived from ancient boundary markers, are similar to caryatids and atlantes in having human heads.

Grotto under N. terrace, Villa Medici, Poggio a Caino

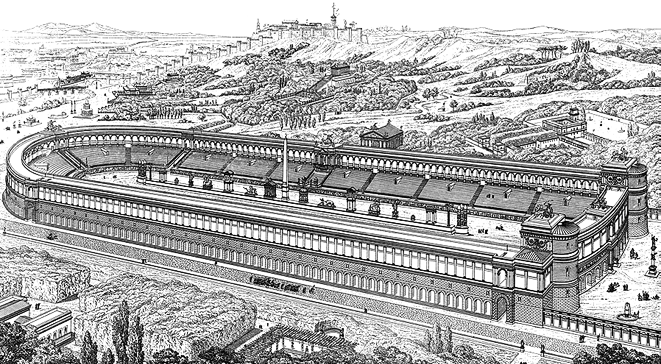

HIPPODROME. Roman stadium containing a long racetrack that was used for chariot races. The racetrack had long straight sides and curved ends. Obelisks often stood at the center, and bronze representations of four-horse teams pulling chariots, like those used on triumphal arches, commonly crowned the gates.

Nero's Hippodrome (track surrounded by seating for chariot races)

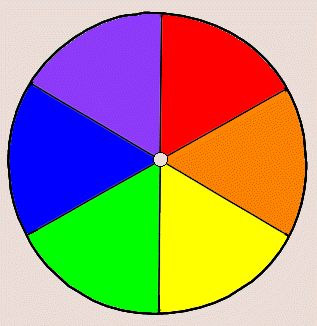

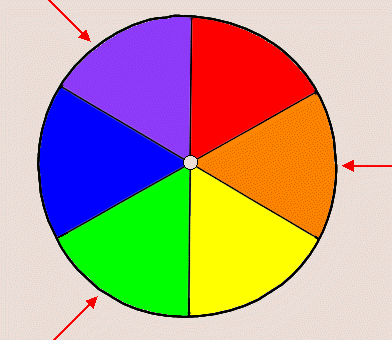

HUE. The dimension of color referring to its position in a continuum of red-orange-yellow-green-blue-purple, which is generally displayed as a circular configuration called the color wheel. Red, yellow, and blue are the primary colors from which the other colors can be mixed. Orange, green, and purple are the secondary colors. Colors that are adjacent are referred to as analogous and colors that are across from each other as complementary.

![]()

ICON. Sacred image painted on wood. Icons were especially widely used in the Eastern Orthodox religion. The Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ, and the saints were typically depicted.

Sassetta's St. Francis in Ecstasy, 1437

ICONOGRAPHY. The study of subject matter in the figurative arts, with particular attention to symbols, attributes, and allegorical references. Iconography addresses an art work's content as opposed to its form.

Botticelli's Tobias and the Angel

Tobias can be identified by the fish he carries and the presence of his traveling companion, the archangel Raphael, who travels with him to Medina on an errand for Tobias' father, Tobit. The dog, which is not an attribute of either figure individually, is a marker for their journey together. |

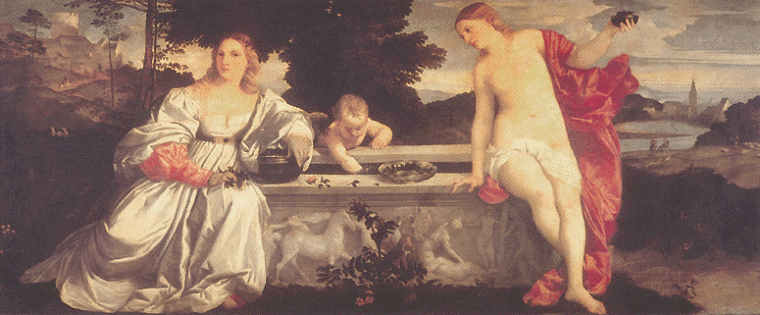

ICONOLOGY. Term invented by the art historian Erwin Panofsky for his expansion of the iconographical approach to include the cultural history and meaning of images.

Titian's Sacred and Profane Love, 1515 Although art historians do not agree on the meaning of this work, many accept Panofsky's interpretation that the two women represent dual aspects of love: the sacred and the profane. This interpretation depends not only on the identification of certain symbols like the wilted rose petals on the ledge, which suggest the withering of temporal beauty, but also on the knowledge that Neoplatonic ideas were part of the intellectual climate of the Renaissance. |

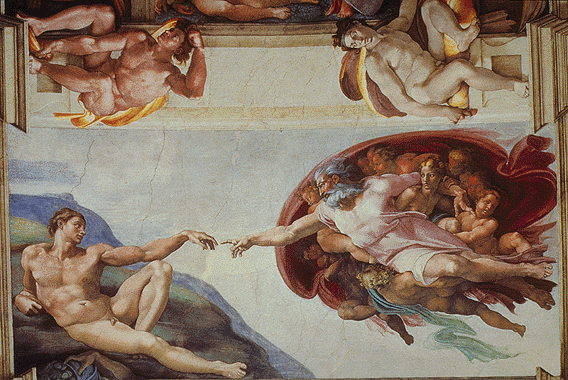

IDEALISM. In art, rendering the subject as an ideal form rather than with the imperfections of real life, as in realism. Underlying this approach is an assumption that art should be a morally uplifting experience from which human improvement might result if ideals of beauty and virtue were presented as models. In ancient Greek culture, "the beautiful" and "the good" were synonymous, both ideas being contained in the same word. In the Renaissance, the philosophical basis of this belief was Plato's Theory of Ideas, which put forth the notion that beyond the specific examples of real men, women, objects, etc. were ideal forms in these categories. Plato and his followers regarded these abstract ideal forms as the true reality and the various material objects as mere copies. In art, this philosophy led to the depiction of a beautiful race of superbeings whose individual traits were minimized. Also see Neo-Platonism.

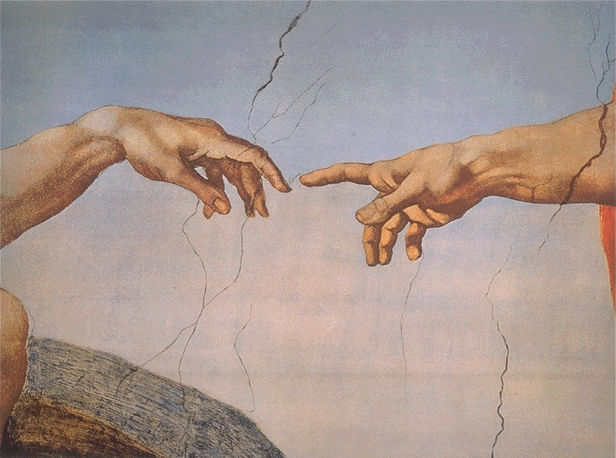

Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel ceiling, Vatican, 1511-12

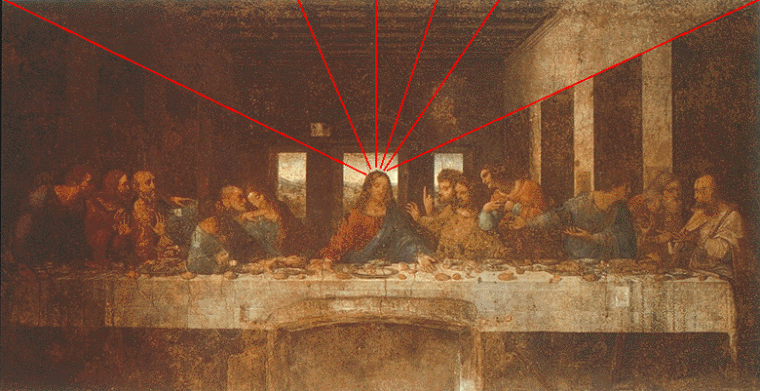

ILLUSIONISM. Realistic painting style that seeks to present a false reality by using such devices as life-size scale, a viewpoint that is consistent with the viewer's eye-level, the placement of lights and shadows in accordance with the actual light sources of the room, the depiction of architectural features that correspond to and appear to extend the actual architecture, and the placement of figures so that they appear to overlap adjacent features. Illusionistic depictions in the Renaissance include landscapes that appear to recede beyond fictive architecture and objects that invite viewers to lift them from two-dimensional shelves. Although illusionism was popular in Greek and Roman art, no models of it were available to Renaissance artists. Masaccio led the way with his incorporation of illusionistic devices in the Holy Trinity altarpiece. Mantegna, Giulio Romano, and Veronese excelled at illusionistic decoration. See trompe l'oeil.

Detail from Giulio Romano's Sala dei Cavalli, Palazzo del Tè, Mantua, c. 1526-34

IMPASTO. Thick application of paint making the texture of individual strokes apparent. "Impasto" is derived from the Italian word for "in paste."

Titian's Crowning with Thorns, c. 1570 With detail

IMPOST. A projecting cap on a pier or wall from which the ends of an arch usually spring. In the construction of arches, impost blocks serve as ledges for the centering. In the Renaissance, impost blocks were sometimes articulated as sections of entablature.

INK. Colored fluid that is used for writing and drawing. Noted for its permanency, ink has a thin consistency that makes it suitable for use with a pen or brush. Ink was invented in the middle of the third millennium BC by the Chinese. Its eastern origin accounts for the black variety being called "Indian" or "India" ink. A brown ink that was also widely used in the Renaissance is called "sepia" in reference to its derivation from a secretion of the cuttlefish, a squid-like marine creature of the genus Sepia. Ink drawings were generally made with a quill pen, and shading was indicated by hatching or wash.

Leonardo's Study of a Woman's Braided Hair

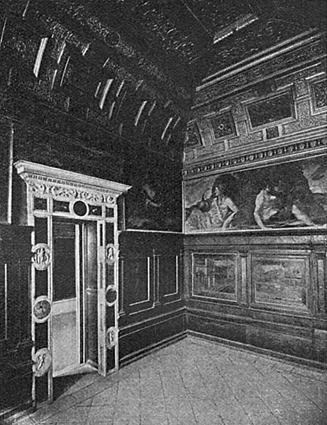

INTARSIA. An inlay technique in which pieces of hard material like wood or stone are cut to fit together like pieces of a puzzle. In Italy, it was used in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the Veneto, Tuscany, and neighboring regions. In the fifteenth century, subject matter for works using intarsia often included architectural scenes and trompe l'oeil still lifes. The most famous example of the latter was made for the studiolo of Federico II da Montefeltro at the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino.

Intarsia chest, 15th century

INTENSITY. A hue's purity, which reflects the absence of black, white, or complementary hues (colors that are across from each other on the color wheel. This dimension of color is also called "saturation."

|

High Intensity Titian's Cardinal Alessandro Farnese |

Low Intensity Fra Lippi's Madonna and Child with Two Angels |

INTERNATIONAL GOTHIC STYLE. Style of painting that was current in Europe from 1375 to 1425. It is believed to have originated in France. The style is characterized by several qualities.

●Decorativeness. Intense color, gilding, and details like patterned fabrics, gold embroidery, and fine metal work create a rich decorative surface.

●Courtly subjects. The subject matter includes images of courtly life like richly dressed aristocrats, many of which were portraits, along with horses in fine trappings, dogs, and exotic animals.

●Flatness. Figures and objects are presented as two-dimensional surfaces rather than bodies in space.

Benozzo Gozzoli's Procession of the Magi, Palazzo Medici, 1459

INTONACO. The upper layer of smooth plaster to which the paint was applied in fresco painting. The intonaco is applied over the arriccio, an underlayer of rough plaster, in patches corresponding to the amounts the fresco painter anticipated painting in a single day (giornata) so that the paint would be absorbed into the plaster before it dried.

IONIC ORDER. Order developed by the Greeks that is distinguished by a capital with prominent volutes, a slender column shaft that is fluted with channels that do not touch, and a frieze that is either plain or carved with a continuous design rather than with triglyphs and metopes.

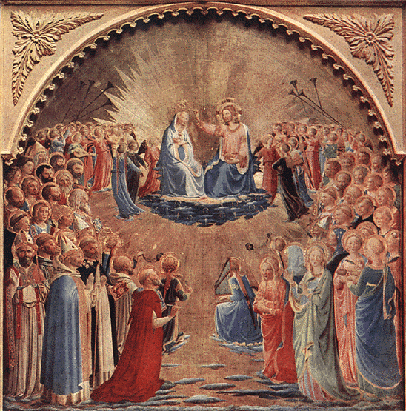

ISOCHROMATISM. Distribution of areas of the same color to achieve compositional balance. For instance, in fourteenth-century enthroned-Madonna subjects, the colors of the robes of the angels on the left side might mirror those in the equivalent positions on the right.

Fra Angelico's Coronation of the Virgin

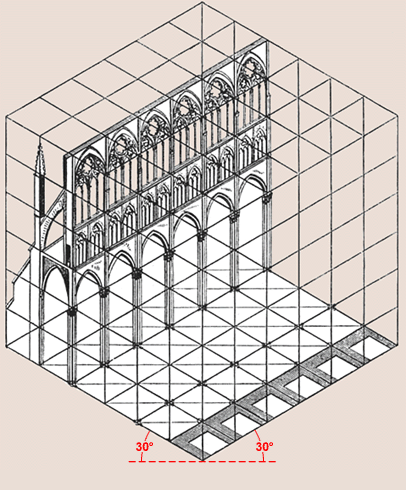

ISOMETRIC PROJECTION. Representation of an obliquely positioned building that is three-dimensional but lacks the diminution with distance of perspective because all receding lines are projected at the same angle to the horizon. This differs from linear-perspective renderings of obliquely positioned structures in which all receding lines converge at two points on the horizon. The term "isometric projection" refers to the use of the same (iso = same) angle to horizontal, usually 30 degrees or greater, of the two walls of the front corner.

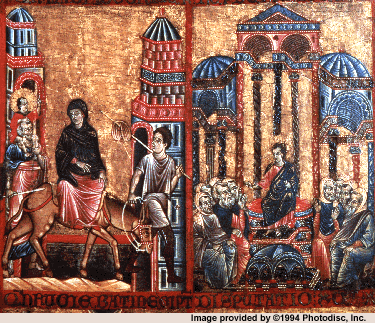

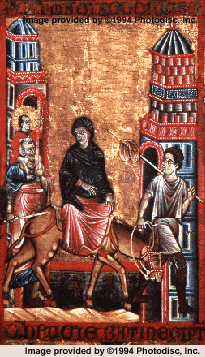

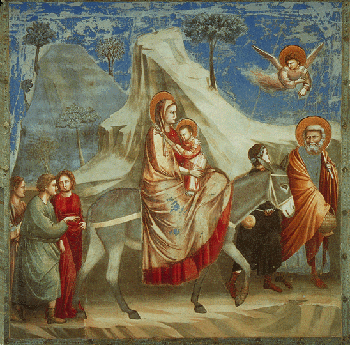

ITALO-BYZANTINE STYLE. Name of a style of art and architecture in Italy that fused the local style with the Byzantine style.

|

|

Adoration of the Magi |

The Circumcision |

Flight Into Egypt |

Dispute in the Temple |

![]()

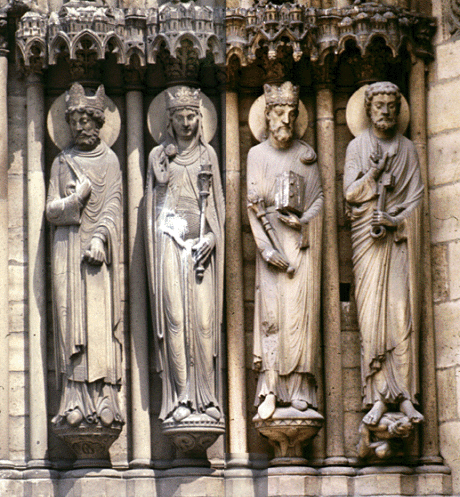

JAMB. Vertical support used in pairs at the sides of doors and windows. The jambs of Romanesque and Gothic church portals, which were generally angled outward, were often carved as a series of standing figures. See archivolt.

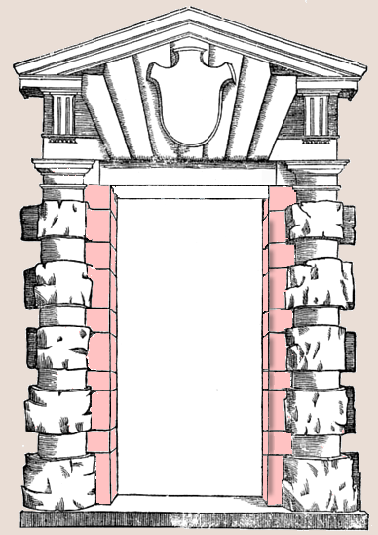

Serlio's design for a rusticated doorway, Architettura, Book IV (1537). |

bottom: Jamb figures of Notre Dame

|

![]()

KEYSTONE. Central voussoir of an arch, which is inserted last during construction. Early Tuscan keystones were usually treated the same as the other voussoirs, but sometimes they were distinguished by contrasting size or texture. Renaissance keystones were often accentuated by relief carving in the form of consoles, masks, or busts. Mannerists like Giulio Romano manipulated keystones in a variety of ways.

![]()

LANTERN. Relatively small structure that surmounts a dome, roof, or tower. It is usually open or has windows, and its light is often admitted to the main structure below.

Brunelleschi's Lantern of Florence Cathedral, 1446-67

LAPIS LAZULI. An expensive blue mineral from which the pigment for ultramarine blue is made. Because of its cost and rarity, lapis lazuli, whose use was specified in contracts, was usually reserved for the clothes of important figures like the Virgin Mary.

Ghirlandaio's Madonna and Child with Saints

LAST JUDGMENT. Final reckoning to reward the virtuous and punish the wicked at the end of the world. Although the notion was mentioned twice in the Old Testament, the judgment scenes depicted in the Renaissance were usually based on Christ’s description in Matthew (25:31-46) or the Apocalypse, which is also called the Revelation of St. John. At the end of the world, the archangel Gabriel blows his trumpet to call up the dead from their burial places for the final judgment. Christ sits in judgment on a throne surrounded by Apostles, saints, church elders, John the Baptist, and the Virgin Mary, who intercedes, for mercy on those being judged. Christ separates the saved and the damned as a shepherd separates sheep from goats (Matthew 25:33), giving rise to the use of these animals symbolically in Byzantine judgment scenes. In Renaissance scenes, those judged to be righteous are taken up to heaven by angels on the right side of Christ, and those found to be sinners are taken downward to hell and tortured by demons on his left side. The archangel Michael, who has wings and wears armor, assists in the judging by weighing the souls on scales, a theme that dates back to ancient Egypt. It was popular in Italy in the 14th century and again in the late 16th century in the wake of the Counter Reformation, when repentance was emphasized as part of the Church's effort at reform. See Dome of Florence Cathedral.

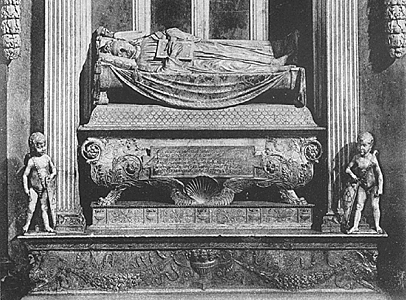

Detail, The Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, by Michelangelo